Vroeg-Spanje en Portugal

Hispania Citerior en Ulterior

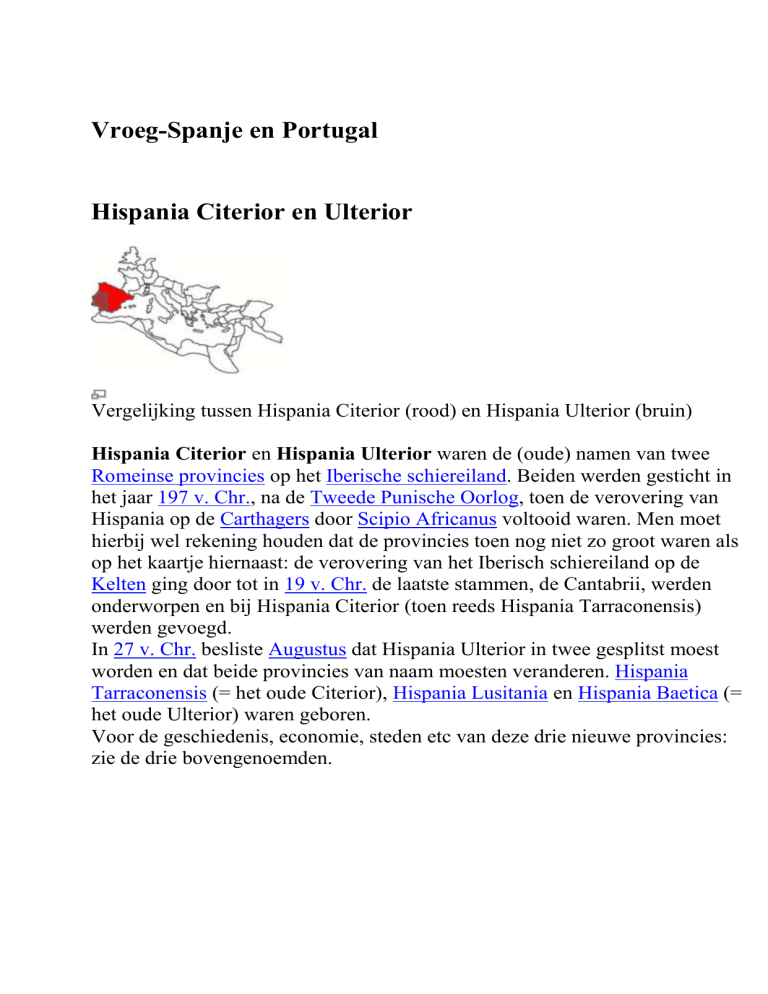

Vergelijking tussen Hispania Citerior (rood) en Hispania Ulterior (bruin)

Hispania Citerior en Hispania Ulterior waren de (oude) namen van twee

Romeinse provincies op het Iberische schiereiland. Beiden werden gesticht in

het jaar 197 v. Chr., na de Tweede Punische Oorlog, toen de verovering van

Hispania op de Carthagers door Scipio Africanus voltooid waren. Men moet

hierbij wel rekening houden dat de provincies toen nog niet zo groot waren als

op het kaartje hiernaast: de verovering van het Iberisch schiereiland op de

Kelten ging door tot in 19 v. Chr. de laatste stammen, de Cantabrii, werden

onderworpen en bij Hispania Citerior (toen reeds Hispania Tarraconensis)

werden gevoegd.

In 27 v. Chr. besliste Augustus dat Hispania Ulterior in twee gesplitst moest

worden en dat beide provincies van naam moesten veranderen. Hispania

Tarraconensis (= het oude Citerior), Hispania Lusitania en Hispania Baetica (=

het oude Ulterior) waren geboren.

Voor de geschiedenis, economie, steden etc van deze drie nieuwe provincies:

zie de drie bovengenoemden.

S. Africanus

Pre-Roman peoples of the Iberian Peninsula

Main language areas in Iberia circa 250 BC.

This is a list of the Pre-Roman people of the Iberian peninsula (the Roman Hispania modern Andorra, Portugal and Spain).

Contents

1 Non Indo-European

2 Indo-European

3 See also

4 External links

Non Indo-European

Aquitanians and other Proto-Basques

o Aquitani

o Autrigones

o Cantabri

o Caristii

o Varduli

o Vascones

Iberians

o Ausetani

o Bastetani

o Bastuli

o Cassetani

o Contestani

o Edetani

o Ilercavones

o Ilergetes

o Indigetes

o Laietani

o Oretani - some consider them Celtic [1].

Tartessians

o Turdetani

Cynetes or Conii - originally probably Tartessians or

similar, later celtized by the Celtici.

Indo-European

Indo-European peoples

o Proto-Celtic & Celtic

Astur

Bletonesii

Bracari

Gallaecians or Callaici

Carpetani

Celtiberians

Celtici

Coelerni

Equaesi

Grovii

Interamici

Leuni

Limici

Luanqui

Lusitanians

Lusones

Narbasi

Nemetati

Paesuri

Quaquerni

Seurbi

Tamagani

Tapoli

Turduli Veteres

Turduli

Turdulorum Oppida

Turodi

Vacceos

Vettones

Zoelae

Prehistoric Iberia

The Prehistory of the Iberian peninsula begins with the arrival of the first

hominins c.900,000 BP and ends with the Punic Wars, when the territory

enters the domains of written history. In this long period, some of its most

significative landmarks were to host the last stand of the Neanderthal people,

to develop some of the most impresive Paleolithic art, alongside with southern

France, to be the seat of the earliest civilizations of Western Europe and

finally to become a most desired colonial objective due to its strategical

position and its many mineral riches.

Lower and Middle Paleolithic

Hominin inhabitation of the Iberian Peninsula dates from the Paleolithic. Early

hominin remains have been discovered at a number of sites on the peninsula.

Significant evidence of an extended occupation of Iberia by Neandertal man

has also been discovered. Homo sapiens first entered Iberia towards the end of

the Paleolithic. For a time Neanderthals and modern humans coexisted until

the former were finally driven to extinction. Modern man continued to inhabit

the peninsula through the Mesolithic and Neolithic periods.

Homo neanderthalensis La Ferrassie 1

Iberia has a wealth of prehistoric sites. Many of the best preserved prehistoric

remains are in the Atapuerca region, rich with limestone caves that have

preserved a million years of human evolution. Among these sites is the cave of

Gran Dolina, where six hominin skeletons, dated between 780,000 and one

million years ago, were found in 1994. Experts have debated whether these

skeletons belong to the species Homo erectus, Homo heidelbergensis, or a

new species called Homo antecessor. In the Gran Dolina, investigators have

found evidence of tool use to butcher animals and other hominins, the first

evidence of cannibalism in a hominin species. Evidence of fire has also been

found at the site, suggesting they cooked their meat.

Also in Atapuerca, is the site at Sima de los Huesos, or "Pit of Bones".

Excavators have found the remains of 30 hominins dated to about 400,000

years ago. The remains have been tentatively classified as Homo

heidelbergensis and may be ancestors of the Neanderthals. No evidence of

habitation has been found at the site except for one stone hand-ax, and all of

the remains at the site are of young adults or teenagers. The age similarity

suggests the remains were not the result of accidents. The seemingly

deliberate placement of remains and lack of habitation may mean that the

bodies were deliberately interred in the pit as a place of burial, which would

make the site the first evidence of hominin burial.

Neanderthals in Europe (simplified).

Around 200,000 BC, during the Lower Paleolithic period, Neanderthals first

entered the Iberian Peninsula. Around 70,000 BC, during the Middle

Paleolithic period the last ice age began and the Neanderthal Mousterian

culture was established. Around 35,000 BC, during the Upper Paleolithic, the

Neanderthal Châtelperronian cultural period began. Emanating from Southern

France this culture extended into Northern Iberia. This culture continued to

exist until around 28,000 BC when Neanderthal man faced extinction, their

final refuge being present-day Portugal.

Neanderthal remains have been found at a number of sites on the Iberian

Peninsula. A Neanderthal skull was found in Forbes's Quarry in Gibraltar in

1848 making Spain the first country where remains of Neanderthals were

found. Neanderthals were not recognized as a separate species until the

discovery of remains in Neandertal, Germany in 1856. Subsequent

Neanderthal discoveries in Gibraltar have also been made including the skull

of a four-year-old child and preserved excrement on top of baked mussel

shells.

In Zafarraya a Neanderthal mandible and Mousterian tools, associated with the

Neanderthal culture, were found in 1995. The mandible was dated to about

28,000 BC and the tools to about 25,000 BC. These dates make the Zafarraya

remains the youngest evidence of Neanderthals and have expanded the

timeline of Neanderthal existence. The more recent dating of the remains also

provides the first evidence for prolonged co-existence between Neanderthals

and modern man. L'Arbreda Cave in Catalonia contains Aurignacian cave

paintings, as well as earlier remains from Neanderthals. Some have also

suggested that the newer remains in Iberia suggest Neanderthals were driven

out of Central Europe by modern man to the Iberian peninsula where they

sought refuge.

Upper Paleolithic

Early Upper Paleolithic

The Chatelperronian culture (typically associated with Neanderthal man) is

found in the Cantabrian region and in Catalonia.

The Aurignacian culture (work of Homo sapiens) succeeds it and has the

following periodization[1]:

Archaic Aurignacian: found in Cantabria (Morín and El Pendo caves),

where it alternates with Chatelperronian, and in Catalonia. The C-14

dates for Morín cave are relatively late in the European context: c.

28,500 BP, but the occupation dates for El Pendo (where it's older than

Chatelperronian layers) must be of earlier date.

Typical Aurignacian: it is found in Cantabria (Morín, El Pendo,

Castillo), the Basque Country (Santimamiñe) and Catalonia. The

radicarbon datations give the following dates: 32,425 and 29,515 BP.

Evolved Aurignacian: it is found in Cantabria (Morin, El Pendo, El

Otero, Hornos de la Peña), Asturias (El Cierro, El Conde) and Catalonia.

Final Aurignacian: in Cantabria (El Pendo), after the Gravettian

interlude.

In the Mediterranean area (south of the Ebro), Aurignacian remains have been

found sparsely distributed in the Lands of Valencia (Les Mallaetes) and

Murcia (Las Pereneras) and Andalusia (Higuerón), as far west as Gibraltar

(Gorham's Cave). The radiocarbon dates available are: 29,100 BP (Les

Mallaetes), 28,700 BP and 27,860 BP (Gorham's Cave).

Middle Upper Paleolihic

Gravettian

The Gravettian culture followed the steps of the Aurignacian expansion but its

remains are not very aboundant in the Cantabrian area (north), while in the

southern region they are more common.

In the Cantabrian area all Gravettian remains belong to late evolved phases

and are found always mixed with Aurignacian technology. The main sites are

found in the Basque Country (Lezetxiki, Bolinkoba), Cantabria (Morín, El

Pendo, El Castillo) and Asturias (Cueto de la Mina). It is archeologically

divide in two phases characterized by the amount of Gravettian elements: the

phase A has a C-14 date of c.20,710 BP and the phase B is of later date.

The Cantabrian Gravettian has been paralleled to the Perigordian V-VII of the

French sequence. It eventually vanishes from the archaeological sequence and

is replaced by an "Aurignacian renaissance", at least in El Pendo cave. It is

considered "intrusive", in contrast with the Mediterranean area, where it

probably means a real colonization[1].

In the Mediterranean region, the Gravettian culture also had a late arrival.

Nevertheless, the south-east has an important number of sites of this culture,

specially in he Land of Valencia (Les Mallaetes, Parpaló, Barranc Blanc,

Meravelles, Coba del Sol, Ratlla del Musol, Beneito). It is also found in the

Land of Murcia (Palomas, Palomarico, Morote) and Andalusia (Los

Borceguillos, Zájara II, Serrón, Gorham's Cave).

The first indications of modern human colonization of the interior and the

west of the peninsula are found only in this cultural phase, with a few late

Gravettian elements found in the Manzanares valley (Madrid) and Salemas

cave (Alemtejo, Portugal).

Solutrean

The Solutrean culture shows its earliest appearances in Laugerie Haute

(Dordogne, France) and Les Mallaetes (Land of Valencia), with radiocarbon

dates of 21,710 BP and 20,890 BP respectively[1]. In the Iberian peninsula it

shows three different facies:

The Iberian (or Mediterranean) facies is defined by the sites of Parpalló and

Les Mallaetes in the province of Valencia. They are found immersed in

important Gravettian perdurations that would eventually redefine the facies as

"Gravettizing Solutrean"[1]. The archetypical sequence, that of Parpalló and

Les Mallaetes caves, is:

Initial Solutrean.

Full or Middle Solutrean, dated in its lower layers to 20,180 BP.

An sterile layer with signs of intense cold that is related to the Last

Glacial Maximum.

Upper or Evolved Solutrean, including bone tools and also needles of

this material.

These two caves are surrounded by many other sites (Barranc Blanc,

Meravelles, Rates Penaes, etc.) that show only a limited impact of Solutrean

and instead have many Gravettian perdurations, showing a convergence that

has been named as "Gravetto-Solutrean".

Solutrean is also found in the Land of Murcia, Mediterranean Andalusia and

the lower Tagus (Portugal). In the Portuguese case there are no signs of

Gravettization.

The Cantabrian facies shows two markedly different tendencies in Asturias

and the Vasco-Cantabrian area. The oldest findings are all in Asturias and lack

of the initial phases, beginning with the full Solutrean in Las Caldas (Asturias)

and other nearby sites, followed by evolved Solutrean, with many unique

regional elements. Radiocarbon dates oscilate between 20,970 and 19,000

BP[1].

In the Vasco-Cantabrian area instead the Gravettian influences seem persistent

and the typical Solutrean foliaceous elements are minority. Some transitional

elements that prelude the Magdalenian, like the monobiselated bone spear

point, are already present. Most important sites are Altamira, Morín, Chufín,

Salitre, Ermittia, Atxura, Lezetxiki, and Santimamiñe.

In northern Catalonia there is an early local Solutrean, followed by scarce

middle elements but with a well developed final Solutrean. It is related to the

French Pyrenean sequences. Main sites are Cau le Goges, Reclau Viver and

L'Arbreda.

In the region of Madrid there were some findings attributed to Solutrean that

are today missing.

Late Upper Paleolithic

This phase is defined by the Magdalenian culture, even if in the Mediterranean

area the Gravettian influence is still persistent.

In the Cantabrian area, the early Magdalenian phases show two different

facies: the "Castillo facies" evolves locally over final Solutrean layers, while

the "Rascaño facies" appears in most cases directly over the natural soil (no

earlier occupations of these sites).

In the second phase, the lower evolved Magdalenian, there are also two facies

but now with a geographical divide: the "El Juyo facies" is found in Asturias

and Cantabria, while the "Basque Country facies" is only found in this region.

The dates for this early Magdalenian period oscilate between 16,433 BP for

Rascaño cave (Rascaño facies), 15,988 and 15,179 BP for the same cave (El

Juyo facies) and 15,000 BP for Altamira (Castillo facies). For the Basque

Country facies the cave of abauntz has given 15,800 BP[1].

The middle Magdalenian shows less aboundance of findings.

The upper Magdalenian is closely related to that of southern France

(Magdalenian V and VI), being characterized by the presence of harpoons.

Again there are two facies (called A and B) that appear geographically

interwined, though the facies A (dates: 15,400-13,870 BP) is absent in the

Basque Country and the facies B (dates 12,869-12,282 BP) is rare in Asturias.

In Portugal there have been some findings of the upper Magdalenian north of

Lisbon (Casa da Moura, Lapa do Suão). A possible intermediate site is La

Dehesa (Salamanca, Spain), that is clearly associated with that of the

Cantabrian area.

In the Mediterranean area, Catalonia again is directly connected with the

French sequence, at least in the late phases. Instead the rest of the region

shows a unique local evolution known as Parpallense.

The sometimes called Parpalló "Magdalenian" (extended by all the south-east)

is actually a continuity of the local Gravetto-Solutrean. Only the late upper

Magdlenian actually includes true elements of this culture, like protoharpoons. Radicarbon dates for this phase are of c. 11,470 BP (Borran Gran).

Other sites give later dates that actually approach the Epi-Paleolithic[1].

Paleolithic art

Altamira cave ceiling

Together with France, the Iberian peninsula is one of the prime areas of

Paleolithic cave paintings. This artistic manifestation is found most

importantly in the northern Cantabrian area, where the earliest manifestations

(Castillo, El Conde) are as old as Aurignacian times, even if rare.

The practice of this mural art increases in frequency in the Solutrean period,

when the first animals are drawn, but it is not until the Magdalenian cultural

phase when it becomes truly widespread, being found in almost every cave.

Most of the representations are of animals (bison, horse, deer, bull, reindeer,

goat, bear, mammouth, moose) and are painted in ochre and black colors but

there are exceptions and human-like forms as well as abstract drawings also

appear in some sites.

In the Mediterranean and interior areas, the presence of mural art is not so

aboundant but exists as well since the Solutrean.

Also, several examples of open-air art exist, such as the monumental Côa

Valley (Portugal), Domingo García and Siega Verde (both in Spain).

Archaeogenetics

World map of human migrations

Around 40,000 BC the first large settlement of Europe by modern humans,

nomadic hunter-gathereres came from the steppes of Central Asia,

characterized by the M173 mutation in the Y chromosome, defining them as

an haplogroup R population. When the last ice age reached its maximum

extent, these modern humans took refuge in Southern Europe, namely in

Iberia, and in the steppes of southern Ukraine and Russia.

From around 32,000 to 21,000 BC the modern human Aurignacian culture

dominated Europe. Around 30,000 BC a new wave of modern humans made

their way from Southern France into the Iberian peninsula. Here, this

genetically homogenous population (characterized by the M173 mutation in

the Y chromosome), developed the M343 mutation, giving rise to the R1b

Haplogroup, still dominant in modern Portuguese and Spanish populations.

Around 28,000 BC the Gravettian culture began to succeed the Aurignacian.

Epipaleolithic

Around 10,000 BC an interstadial deglaciation called the Allerød Oscillation

occurred, weakening the rigorous conditions of the last ice age. This climatic

change also represents the end of the Upper Palaeolithic period, beginning the

Epipaleolithic.

As the climate became warmer, the late Magdalenian peoples of Iberia

modified their technology and culture. The main techno-cultural change is the

process of microlithization: the reducton of size of stone and bone tools, also

found in other parts of the World. Also the cave sanctuaries seem to be

abandoned and art becomes rarer and mostly done on portable objects, such as

peebles or tools.

It also implies changes in diet, as the megafauna virtually disappears when the

steppe becomes woodlands. In this period, hunted animals are of smaller size,

typically deer or wild goats, and seafood becomes an important part of the diet

Azilian

The first Epipaleolithic culture is the Azilian, also known as microlaminar

microlithism in the Mediterranean. This culture is the local evolution of

Magdalenian, parallel to other regional derivatives found in Central and

Northern Europe. Original from the Franco-Cantabrian region, it eventually

expands to Mediterranean Iberia as well.

An archetypical Azilian site in the Iberian peninsula is Zatoya (Navarre),

where it is difficult to discern the early Azilian elements from those of late

Magdalenian (this transition dated to 11,760 BP [1]). Full Azilian in the same

site is dated to 8,150 BP, followed by appearance of geometric elements at a

later date, that continue until the arrival of pottery (subneolithic stage).

In the Mediterranean area, virtually this same material culture is often named

microlaminar microlithism because it lacks of the bone industry typical of

Franco-Cantabrian Azilian. It is found in parts of Catalonia, Lands of Valencia

and Murcia and Mediterranean Andalusia. It has been dated in Les Mallaetes

at 10,370 BP[1].

Geometrical microlithism

In the late phases of the Epipaleolithic a new trend arrives from the north: the

geometrical microlithism, directly related to Sauveterrian and Tardenoisian

cultures of the Rhin-Danube region.

While in the Franco-Cantabrian region it has a minor impact, not altering the

Azilian culture substantially, in Mediterranean Iberia and Portugal its arrival is

more noticeable. The Mediterranean geometrical microlithism has two facies:

The Filador facies is directly related to French Sauveterrian and is found

in Catalonia, north of the Ebro river.

The Cocina facies is more widespread and, in many sites (Málaga,

Portugal), shows a strong dependence of fishing and seafood gathering.

The Portuguese sites (south of the Tagus, Muge group) have given dates

of c.7350 BP[1].

Asturian

An rather mysterious exception to generalized microlithism is the so called

Asturian culture, actually identified by a single fossil: the Asturian pick-axe,

and found only in coastal locations, specially in Eastern Asturias and Western

Cantabria. It is believed that the Asturian tool was used for seafood gathering.

Neolithic

In the 6th millennium BCE Andalusia experiences the arrival of the first

agriculturalists. Their origin is uncertain (though North Africa is a serious

candidate) but they arrive with already developed crops (cereals and legumes).

The presence of domestic animals instead is unlikely, as only pig and rabbit

remains have been found and these could belong to wild animals. They also

consumed large amounts of olives but it's uncertain too wether this tree was

cultivated or merely harvested in its wild form. Their typical fossil is the La

Almagra style pottery, quite variegated[1].

The Andalusian Neolithic also influenced other areas, notably Southern

Portugal, where, soon after neolithization, the first dolmen tombs begin to be

built c.4800 BCE, being possibly the oldest of their kind anywhere[1].

C.4700 BCE Cardium Pottery Neolithic culture (also known as Mediterranean

Neolithic) arrives to Eastern Iberia. While some remains of this culture have

been found as far west as Portugal, its distribution is basically Mediterranean

(Catalonia, Valencian region, Ebro valley, Balearic islands).

The interior and the northern coastal areas remain largely marginal in this

process of spread of agriculture. In most cases it would only arrive in a very

late phase or even already in the Chalcolithic age, together with Megalithism.

Chalcolithic

An interpretation of the developement of the European Megalithic Culture

The Chalcolithic or Copper Age is the earliest phase of metallurgy. Copper,

silver and gold started to be worked then, though these soft metals could

hardly replace stone tools for most purposes. The Chalcolithic is also a period

of increased social complexity and stratification and, in the case of Iberia, that

of the rise of the first civilizations and of extense exchange networks that

would reach to the Baltic and Africa.

The conventional date for the beginning of Chalcolithic in Iberia is c. 3000

BCE. In the following centuries, specially in the south of the peninsula, metal

goods, often decorative or ritual, become increasingly common. Additionally

there is an increased evidence of exchanges with areas far away: ambar from

the Baltic and ivory and ostrich-egg products from Northern Africa[1].

It is also the period of the great expansion of Megalithism, with its associated

collective burial practices. In the early Chalcolithic period this cultural

phenomenon, maybe of religious undertones, expands along the Atlantic

regions and also through the south of the peninsula (additionally it's also found

in virtually all European Atlantic regions). In contrast, most of the interior and

the Mediterranean regions remain refractary to this phenomenon.

Another phenomenon found in the early chalcolithic is the development of

new types of funerary monuments: tholoi and artificial caves. These are only

found in the more developed areas: southern Iberia, from the Tagus estuary to

Almería, and SE France.

Eventually, c. 2600 BCE, urban communities begin to appear, again specially

in the south. The most important ones are Los Millares in SE Spain and

Zambujal (belonging to Vila Nova de São Pedro culture) in Portuguese

Estremadura, that can well be called civilizations, even if they lack of the

literary component.

Extent of the Beaker culture

It is very unclear if any cultural influence originated in the Eastern

Mediterranean (Cyprus?) could have sparked these civilizations. On one side

the tholos does have a precedent in that area (even if not used yet as tomb) but

on the other there is no material evidence of any exchange between the

Eastern and Western Mediterranean, in contrast with the aboundance of goods

imported from Northern Europe and Africa[1].

Since c. 2150 BCE, the Bell Beaker culture intrudes in Chalcolithic Iberia.

After the early Corded style beaker, of quite clear Central European origin, the

peninsula begins producing its own types of Bell Beaker pottery. Most

important is the Maritime or International style that, associated specially with

Megalithism, is for some centuries aboundant in all the peninsula and southern

France.

Since c. 1900, the Bell Beaker phenomenon in Iberia shows a regionalization,

with different styles being produced in the various regions: Palmela type in

Portugal, Continental type in the plateau and Almerian type in Los Millares,

among others[1].

Like in other parts of Europe, the Bell Beaker phenomenon (speculated to be

of trading or maybe religious nature) does not significatvely alter the cultures

it inserts itself in. Instead the cultural contexts that existed previously continue

basically unchanged by its presence.

Bronze Age

Map of Iberian Middle Bronze Age c. 1500 BCE, showing the main cultures,

the two main cities and the location of strategic tin mines

Early Bronze

The center of Bronze Age technology is in the southeast since c.1800 BCE[1].

There the civilization of Los Millares was followed by that of El Argar,

initially with no other discontinuity than the displacement of the main urban

center some kilometers to the north, the gradual appearance of true bronze and

arsenical bronze tools and some greater geographical extension. The Argarian

people lived in rather large fortified towns or cities.

From this center, bronze technology spread to other areas. Most notable are:

Bronze of Levante: in the Land of Valencia. Their towns were smaller

and show intense interation with their neighbours of El Argar.

South-Western Iberian Bronze: in southern Portugal and SW Spain.

These poorly defined archaeological horizons show the presence of

bronze daggers and an expansive trend in northwards direction.

Cogotas I culture (Cogotas II is Iron Age Celtic): the pastoralist peoples

of the plateau become for the first time culturally unified. Their typical

fossil is a rough troncoconic pottery.

Some areas like the civilization of Vila Nova seem to have remained apart

from the spread of bronze metallurgy remaining technically in the Chalcolithic

Middle Bronze

This period is basically a continuation of he previous one. The most noticeable

change happens in El Argar civilization, that adopts the Aegean custom of

burial in pithos[1]. This phase is known as El Argar B, beginning c.1500 BCE.

In the North-West (Galicia and northern Portugal), a region that held some of

the largest reserves of tin (needed to make true bronze) in Western Eurasia

became a focus for mining, incorporating then the bronze technology. Their

typical fossil are bronze axes (Group of Montelavar).

The semi-desertic region of La Mancha shows its first signs of colonization

with the fortified scheme of the Motillas (hillforts). This group is clearly

related to the Bronze of Levante, showing the same material culture[1].

Late Bronze

Map of Iberian Late Bronze Age since c. 1300 BCE, showing the main

cultural areas. Dots show isolated remains of these cultures outside their main

area

C. 1300 BCE several major changes happen in Iberia, among them:

The Chalcolithic culture of Vila Nova vanishes, possibly in direct

relation to the silting of the canal connecting the main city Zambujal

with the sea [2]. It is replaced by a non-urban culture, whose main fossil

is an externally burnished pottery.

El Argar also disappears as such, what had been a vey homogeneous

culture, a centralized state for some, becomes an array of many postArgaric fortified cities.

The Motillas are abandoned.

The proto-Celtic Urnfield culture appears in the North-East, conquering

all Catalonia and some neighbouring areas.

The Lower Guadalquivir valley shows its first clearly differentiated

culture, defined by internally burnished pottery. This group might have

some relation with the semi-historical, yet-to-be-found, Tartessos.

Western Iberian Bronze cultures show some degree of interaction, not

just among them but also with other Atlantic cultures in Britain, France

and elsewhere. This has been called the Atlantic Bronze complex[1].

Iron Age

The Iron Age in the Iberian peninsula has two focus: the Hallstatt-related Iron

Age Urnfields of the North-East and the Phoenician colonies of the South.

Indo-European (Celtic) expansion

Approximate extension of Celts c.400 BCE

Since the late 8th century BCE, the Urnfield culture of North-East Iberia

begins to incorporate Iron metallurgy and, eventually, elements of the Hallstatt

culture. In this period it experiences a clear expansion mainly oriented

upstream along the Ebro river, arriving to La Rioja and (in a hybrid local

form) also to Alava, but also southwards into Castelló, with less marked

influences arriving further south. Some offshots are also detected along the

Iberian mountains, in what can be a prelude of the formation of the Celtiberi[1].

In this period the social differentiation is more visible and there is also

evidence of the existence of local chiefdoms and a horse-riding elite. It is

possible that these transformations represent the arrival of new waves from

Central Europe.

A Castro village in Castro de Baroña, Galicia, Spain

From these outposts in the Upper Ebro and the Iberian montains, the Celtic

culture expanded into the plateau and the Atlantic coast. Several groups can be

described[1]:

The Bernorio-Miraveche group (northern Burgos and Palencia

provinces), that would influence the peoples of the northern fringe.

The Duero group, probable precursor of the Vaccei.

The Cogotas II culture, likely precursor of the Vettones, of marked

cattle-herder nature, that would gradually expand southwards into

Extremadura.

The Lusitanian Castros group, in Central Portugal, precursor of the

Lusitani.

The North-West Castros culture, in Northern Portugal and Galicia,

related to the previous one but with strong peculiarities due to the clear

persistence of the Atlantic Bronze substrate.

All these Indo-European groups have some common elements, like combed

pottery since the 6th century and uniform weaponry.

Since c.600 BCE the Urnifields of the North-East are replaced by the Iberian

culture, in a process that won't be completed until the 4th century BCE[1]. This

physical separation from their continental relatives would mean that the Celts

of the Iberian peninsula never received the cultural influences of La Tène

culture, including Druidism.

Phoenician colonization and influence

Phoenician sarcophagus found in Cadiz

The Phoenicians of Asia, Greeks of Europe, and Carthaginians of Africa all

colonized parts of Iberia to facilitate trade. During the tenth century BC the

first contacts between Phoenicians and Iberia (along the Mediterranean coast)

were made. This century also saw the emergence of towns and cities in the

southern littoral areas of eastern Iberia.

The Phoenicians founded colony of Gadir (modern Cádiz) near Tartessos. The

foundation of Cádiz, the oldest continuously-inhabited city in western Europe,

is traditionally dated to 1104 BC, although, as of 2004, no archaeological

discoveries date back further than the ninth century BC. The Phoenicians

continued to use Cádiz as a trading post for several centuries leaving a variety

of artifacts, most notably a pair of sarcophaguses from around the fourth or

third centuries BC Contrary to myth, there is no record of Phoenician colonies

west of the Algarve (namely Tavira), even though there might have been some

voyages of discovery. Phoenician influence in what is now Portuguese

territory was essentially through cultural and commercial exchange with

Tartessos.

During the ninth century BC the Phoenicians (from the city-state of Tyre

founded the colony of Carthage (in North Africa). During this century

Phoenicians also had great influence on Iberia with the introduction the use of

Iron, of the Potter's wheel, the production of Olive oil and Wine. They were

also responsible for the first forms of Iberian writing, had great religious

influence and accelerated urban development. However, there is little evidence

to support the myth of a Phoenician foundation of the city of Lisbon as far

back as 1300 BC, under the name Alis Ubbo ("Safe Harbour"), even if in this

period there are organized settlements in Olissipona (modern Lisbon, in

Portuguese Estremadura) with clear Mediterranean influences.

There was strong Phoenician influence and settlement in the city of Balsa

(modern Tavira in the Algarve) in the eighth century BC. Phoenician

influenced Tavira was destroyed by violence in the sixth century BC. With the

decadence of Phoenician colonization of the Mediterranean coast of Iberia in

the sixth century BC many of the colonies are deserted. The sixth century BC

also saw the rise of the colonial might of Carthage, which slowly replaced the

Phoenicians in their former areas of dominion.

Greek colonization

The Greek colony at what now is Marseilles began trading with the

Celtiberians on the eastern coast around the eighth century BC. The Greeks

finally founded their own colony at Ampurias, in the eastern Mediterranean

shore (modern Catalonia), during the sixth century BC beginning their

settlement in the Iberian peninsula. There are no Greek colonies west of the

Strait of Gibraltar, only voyages of discovery. There is no evidence to support

the myth of an ancient Greek founding of Olissipo (modern Lisbon) by

Odysseus.

Contents

1 Early hominids

2 Stone Age Modern Man

3 The Metal Ages

4 External links

Early hominids

Spain has a wealth of prehistoric sites. Many of the best preserved prehistoric

remains are in the Atapuerca region, rich with limestone caves that have

preserved a million years of human evolution. Among these sites is the cave of

Gran Dolina, where six hominin skeletons, dated between 780,000 and 1

million years ago, were found in 1994. Experts have debated whether these

skeletons belong to the species Homo erectus, Homo heidelbergensis, or a

new species called Homo antecessor. In the Gran Dolina, investigators have

found evidence of tool use to butcher animals and other hominins, the first

evidence of cannibalism in a hominin species. Evidence of fire has also been

found at the site, suggesting they cooked their meat.

Also in Atapuerca, is the site at Sima de los Huesos, or "Pit of Bones".

Excavators have found the remains of 30 hominins dated to about 400,000

years ago. The remains have been tentatively classified as Homo

heidelbergensis and may be ancestors of the Neanderthals. No evidence of

habitation has been found at the site except for one stone hand-ax, and all of

the remains at the site are of young adults or teenagers. The age similarity

suggests the remains were not the result of accidents. The seemingly

deliberate placement of remains and lack of habitation may mean that the

bodies were deliberately interred in the pit as a place of burial, which would

make the site the first evidence of hominin burial.

Spain was also the first country where remains of Neanderthals were found

when a Neanderthal skull was found in Forbes’s Quarry in Gibraltar in 1848.

However, Neanderthals were not recognized as another species until the

discovering of remains in Neandertal, Germany in 1856. Subsequent

Neanderthal discoveries in Gibraltar have also been made including the skull

of a 4 year old child and preserved excrement on top of baked mussel shells.

Neanderthal remains have been found at other sites within Spain including

Zafarraya where a Neanderthal mandible and Mousterian tools, associated

with the Neanderthal culture, were found in 1995. The mandible was dated to

30,000 years ago and the tools to 27,000. These dates make the Zafarraya

remains the youngest evidence of Neanderthals and have expanded the

timeline of Neanderthal existence. The more recent dating of the remains also

provides the first evidence for prolonged co-existence between Neanderthals

and modern man. Some have also suggested that the newer remains in Spain

suggest Neanderthals were driven out of Central Europe by modern man to the

Iberian peninsula where they sought refuge.

Stone Age Modern Man

Dolmen de Menga (c.2500 BC), Antequera, Andalucia, Spain

Modern men appeared in Spain about 35,000 years ago. At this time, the

Aurignacian culture dominated Europe. L'Arbreda Cave in Catalonia contains

Aurignacian cave paintings, as well as earlier remains from Neanderthals.

Around 20,000 years ago the Aurignacian culture was replaced by that of the

Solutreans, who produced some of the finest flint work of the Stone Age

allowing them to produce lighter projectile weapons, among other advantages.

Despite the superior production abilities of the Solutrean culture, it was

replaced by the Magdalenian culture around 17,000 years ago. The

Magdalenians period marked the height of cave painting.

By far the most significant cave painting site in Spain is Altamira, dated from

about 16,000 to 9,000 BC. Altamira is part of the Cantabrias region where

many more caves with paintings have been found. In Altamira, excavators

have found evidence of human occupation alongside the paintings. These

artifacts include evidence of Solutrean occupation in addition to the

Magdalenians, to whom most of the painting is attributed. The Magdalenians

used charcoal, ochre, haematite, and animal fat to produce the elaborate

display in the cave, the most noteworthy part of which is the Polychrome

Ceiling, with many images of bison and other animals. In addition to the grand

scale of the paintings, the Stone Age artists also used comparatively advanced

artistic techniques. Because of the cave paintings' scale and quality, some have

called Altamira the "The Sistine Chapel of Quaternary art".

The Magdalenians were replaced by the Azilian culture around 10,000 years

ago. The Azilians were the final Paleolithic culture to occupy Spain and

extended their time span into the Mesolithic age. During the Mesolithic

period, cave art continued to advance, especially in the Levant area of Spain.

Spain has many ruins of megalithic monuments created during the Neolithic

period and continued into the Chalcolithic or Copper Age. The monuments

share many similarities with other Megalithic structures throughout Europe,

including those in Brittany and Malta. Dolmens are an especially common

structure built by the Neolithic Spaniards.

The Metal Ages

Phoenician sarcophagus found in Cadiz

Several different cultural groups inhabited Spain before the arrival of

colonizers, and eventually, the Romans.

The Beaker People spread throughout Europe c. 2000 BC and carried with

them knowledge of metal work and their unique pottery designs. The group

may have originated in Spain or Portugal.

The Vascon people inhabited northern Spain from an unknown date. The

Vascons were mentioned by the Romans upon their arrival to Spain. The

Vascons were likely the ancestors of the modern Basque people whose

language, probably the descendent of the Vascon language, has been a

linguistic enigma. The language is outside the regionally dominant family of

Indo-European languages and has no known similarities with other language

families.

The Los Millares culture developed in the third millennium B.C. Centered on

the Los Millares site, the culture spread throughout Andalucia and eastern

Spain. The Los Millares site contained a complex defensive system with

multiple rings of walls and a necropolis with a false dome.

The Los Millares culture fell to the El Argar culture, which lasted from c.

1800 B.C. to c. 1400 B.C. The El Argar mined extensively for their metal

working, including bronze work. The culture disappeared abruptly in 1400

B.C.

Another Spanish lost civilization were the Tartessos, now known only through

historical references and scattered artifacts. The Tartessos people had

advanced knowledge of both metal working and navigation. They sailed to the

British isles to trade for tin and other metals. They then traded these with

Phoenicians who, possibly as early as 1100 B.C., established the city of Cadiz

as a trading post. Tartessos disappeared in the sixth century B.C. Nothing of

Tartessos remains except scattered artifacts and historical references by

classical civilizations. The city is thought to have been at the mouth of the

Guadalquivir river and now likely lies beneath its marshy delta.

The Lady of Baza, made by Iberians

The Iberians arrived in Spain sometime in the third millennium B.C. Most

scholars believe the Iberians came from somewhere farther east in the

Mediterranean, although some have suggested that they originated in North

Africa. The Iberians settled along the eastern coast of Spain. The Iberians

lived in isolated communities structured as tribes. They also had a knowledge

of metal working, including bronze, and agricultural techniques. In later years,

the Iberians evolved into a more complex civilization with urbanized

communities and social stratification. They traded metals with the

Phoenicians, Greeks, and Carthaginians.

The Celts of Europe entered Spain through two separate migrations in the

ninth and seventh centuries B.C. They generally settled along the northern part

of Spain and assimilated various other groups into Celtic culture. The Celts

mixed with the Iberians to form the Celtiberians who integrated the Celtic

tradition and knowledge of iron working with Iberian culture.

The Phoenicians of Asia, Greeks of Europe, and Carthaginians of Africa all

colonized parts of Spain to facilitate trade. The Phoenicians founded Cadiz,

the oldest city in Western Europe, in 1,100 B.C. The Phoenicians continued to

use Cadiz as a trading post for several centuries and left a variety of artifacts,

most notably a pair of sarcophaguses from around the fourth or third centuries

B.C. The Greek colony at what now is Marseilles began trading with the

Celtiberians on the eastern coast around the eight century B.C. The Greeks

finally founded their own colony at Ampurias during the sixth century B.C.

After their defeat by Rome in the First Punic War (which ended in 241 B.C.),

the African based Carthaginians began to extend their conquest of Spain to

expand their empire further into Europe. In the Second Punic War, Hannibal

marched his armies, which included Iberians, from Africa through Spain to

cross the Alps and attack the Romans in Italy. In 202 B.C., At the end of the

Second Punic War, Carthage had lost Spain, and Rome began its conquest and

occupation of the Iberian peninsula, thus beginning the era of Roman Spain.

200 B.C.

Hispania Tarraconensis

Hispania Tarraconensis was een Romeinse provincie in het huidige Spanje.

Tarraconensis besloeg heel het gebied dat Spanje nu is (behalve de

Extremadura en Andalusië) en een deel van het huidige Portugal. Het staat

ook bekend onder zijn (oudere) naam Hispania Citerior.

Inhoud

1 Grenzen

2 Geschiedenis

o 2.1 Bronstijd

o 2.2 Kelten

o 2.3 Grieken en Feniciërs

o 2.4 Carthago en Rome

o 2.5 Hispania Citerior

o 2.6 Hispania Tarraconensis

o 2.7 Tarraconensis na de Romeinen

2.7.1 Vandalen

2.7.2 Visigoten

2.7.3 Moren

3 Volk

4 Religie

5 Economie

Grenzen

Ten oosten van Hispania Tarraconensis lag de Middellandse Zee, wat de

Romeinen passend de Mare Nostrum (Latijn: onze zee). In het zuiden had de

provincie een grens met Hispania Baetica, wat grofweg overeenkomt met het

huidige Andalusia. In het westen lag de Atlantische Oceaan en in het

zuidwesten grensde Tarraconensis aan een andere provincie: Hispania

Lusitania, wat ongeveer overeenkomt met het huidige Portugal.

Geschiedenis

Bronstijd

De Kelten bewoonden heel het Iberische schiereiland: in de bronstijd

behoorden de Keltische nederzettingen (zoals Cortes de Navarra) tot de

Klokbeker-culturen. In de bronstijd was Tin een zeer belangrijke grondstof.

Aangezien de gebieden in het westen van het latere Tarraconensis rijke

voorraden hadden, was de regio een belangrijke handelspartner. Hiervan

getuigt het scheepswrak uit circa 800 v. Chr., gevonden bij Huelva, waar vele

bronzen wapens in zaten, gefabriceerd in Frankrijk.

Kelten

Tegen de 5de eeuw v. Chr. beheersten de Kelten een groot deel van West- en

Centraal Europa, dus ook in Spanje en Hispania Tarraconensis. De Keltische

volkeren waren politiek niet één volk, maar voelden zich cultureel wel

verbonden. Zo was de Hallstatt-cultuur tegen de 5de eeuw v. Chr. in heel

Tarraconensis verspreid. De Keltische volkeren die er woonden heetten:

Gallaeci, Keltiberiërs en Iberiërs, en hadden hun hoofdsteden in Brigantium en

Numantia.

Grieken en Feniciërs

De Grieken stichtten koloniën in het hele Mediterrane gebied, waaronder in

Tarraconensis: tussen 800 en 480 v. Chr. stichtten zij Hemeroskopeion en

Emporion. De rest van de oostkust van Tarraconensis bleef in Keltische

handen. In het zuiden van Hispania werden Fenicische koloniën gesticht: de

beroemdste daarvan is Gades, het huidige Cadiz.

Carthago en Rome

De Feniciërs die met hun hoofdstad in Carthago een zelfstandige mogendheid

waren geworden, waren beter bekend Carthagers. Zij kwamen in het

vaarwater, soms letterlijk, van de Romeinen. Na de Eerste Punische Oorlog

(264-241 v. Chr.) werden Sicilië, Corsica en Sardinië Romeins; de Carthagers

reageerden door hun koloniën in Hispania fors uit te breiden. In 229 v. Chr.

(of 228?) veroverden de Romeinen het noordelijkste deel van Tarraconensis

en in 226 v. Chr. kwamen de partijen overeen de rivier Ebro voortaan als

grens te beschouwen. De Carthaagse koloniën reikten toen al tot aan die rivier

en tot ver in het binnenland, tot aan Numantia.

De Tweede Punische Oorlog (219-201 v. Chr.) veranderde veel voor de regio.

Deze oorlog begon er zelfs: Hannibal viel de vestingstad Saguntum aan, die

Romeins-gezind was terwijl het in de Carthaagse invloedssfeer lag.

De Romeinen reageerden met een tegenaanval: heel Hispania stond op het

spel, en bij nader inzien zelfs hun eigen voortbestaan. De Carthagers vielen

onder Hannibal via Hispania, Gallië en de Alpen het noorden van Italië

binnen. Vandaar ging het verder naar het zuiden, waar zij de Romeinen een

hele tijd het leven zuur maakten. Ondertussen probeerden de Romeinen

Hannibal reeds vanaf (218 v. Chr., Slag bij Cissa), van zijn uitvalbasis te

isoleren door op te marcheren in Hispania.

Rond 210 v. Chr. hadden zij tal van Carthaagse gebieden in Tarraconensis

veroverd en waren tot in Baetica opgemarcheerd. De campagne verliep verder

voorspoedig: onder leiding van Scipio Africanus kwam het leger vanuit Ostia

in 210 in Tarraco, de hoofdstad van het Romeinse Tarraconensis, aan en trok

naar het zuiden. Hannibal zat vast in Zuid-Italië en vele steden vielen zonder

slag of stoot (o.a. Carthago Nova). In 208 stootte Scipio op een Carthaags

leger in Baecula, dat meer landinwaarts lag, maar versloeg het. Twee jaar

later, in 206, gebeurde dat opnieuw, ditmaal in Ilipa. Vandaar uit kon Scipio

Gades innemen; de Carthaagse koloniën in Hispania waren Romeins bezit

geworden: Hispania Citerior. Deze provincie omvatte slechts de kuststreek; de

binnenlanden, waaronder bv. Numantia, waarvan sommige door de Carthagers

waren onderworpen, werden of bleven autonoom.

(voor het verdere verloop van de Punische Oorlogen tussen Rome en

Carthago: zie derde Punische Oorlog)

Hispania Citerior

Na de militaire Romeinse overwinningen op Carthago en Macedonia in 146 v.

Chr. konden de Romeinen meer tijd vrijmaken voor de verdere verovering van

Hispania. In 133 v. Chr. werd Numantia, na een beleg van 20 jaar, door de

Romeinen ingenomen. Dit betekende de ondergang voor de Keltiberiërs, die

daarmee hun hoofdstad verloren. Het verval van de Kelten in Spanje werd pas

echt duidelijk toen de La Tène-periode in de 2de eeuw v. Chr. niet doordrong

tot in Hispania. Tegen 60 v. Chr. werden ook de Lusitanii onderworpen, maar

de Gallaeci (met hoofdstad Brigantium) bleven zich hardnekkig verzetten.

Hispania Tarraconensis in het Romeinse Rijk

Het kustgedeelte (reeds onderworpen) werd rijk. Vanuit de hoofdstad Tarraco

werden heirbanen aangelegd en het gebied traag gekoloniseerd. In 63 v. Chr.

werd Julius Caesar de consul van Hispania Citerior.

Hispania Tarraconensis

In 27 v. Chr. reorganiseerde keizer Augustus Hispania Citerior. Hierbij splitste

hij de provincie in drieën: Hispania Tarraconensis, Hispania Baetica en

Hispania Lusitania. Tijdens de Cantabrische oorlog (29-19 v. Chr. vielen ook

de laatste delen van het Iberische schiereiland: de Cantabrii, inwoners van

Cantabria waren de laatste Kelten die zich in 19 v. Chr. moesten overgeven.

Cantabria werd bij Tarraconensis ingelijfd.

Tarraconensis werd een keizerlijke provincie (d.w.z. dat de keizer een persoon

koos als gouverneur).

Tarraconensis na de Romeinen

Hispania Tarraconensis bleef deel van het Romeinse Rijk tot de grote

volksverhuizingen van de 5de eeuw. Daarna spreekt men eigenlijk niet meer

van Tarraconensis, maar van Spanje.

Vandalen

In 409-410 trokken de Vandaalse Asdingen en Silingen, samen met de Alanen

en Sueven de Pyreneeën over en bereikten Spanje. De in allerijl door de

Romeinen opgeworpen steunpunten ontwijkend, vestigden deze stammen zich

aanvankelijk onder de inheemse bevolking in Noordwest-Spanje. Maar

spoedig verspreidden zij zich van daaruit over Spanje. De Silingen drongen

Baetica binnen en de Asdingen het zuiden van Galicië. De Romeinse keizer

Honorius

zag in de Vandalen bondgenoten tegen zijn rivaal Constantius III en sloot in

411 verdragen. Ondanks deze verdragen werden de twintiger jaren een periode

van wrijving en oorlog. De Romeinen lieten daarom in 415 de Visigoten

overkomen vanuit Gallië naar Spanje om de eerder aangekomen stammen te

vernietigen. In twee jaar tijd werden de Silingen praktisch uitgeroeid en de

Alanen zodanig verzwakt dat deze zich moesten verbinden met de Asdingen.

In 418 verlieten de Visigoten Spanje en bleven de Asdingen en Sueven

gespaard. De Asdingen kregen vaste voet in Andalusië. In 422 versloegen zij

het Romeinse leger en veroverden Carthagena. Ze bouwden een vloot en

veroverden de Balearen. In 429 gingen zij scheep naar Afrika.

Visigoten

In 409 begonnen deze grote volksverhuizingen en dit leidde tot een opstand

van de Basken en de Cantabrii. Na het vertrek van de Vandalen verschenen de

Visigoten. Het uitgeputte West-Romeinse Rijk kon niet meer reageren en het

Visigotische koninkrijk in Hispania was een feit. Deze regering was (mede

met de Ostrogoten) verantwoordelijk voor de echte val van het WestRomeinse Rijk in 476. De Visigotische koningen heersten over heel Spanje en

Portugal en een stukje zuid-Frankrijk, behalve het Suevenkoninkrijk in het

noordwesten, dat veroverd werd in 585 en Baskenland, dat nooit veroverd

werd. Het bestuur had veel innerlijke twisten, waardoor Justinianus I in 554

het zuidelijk deel van Tarraconensis en Baetica kon veroveren. Tegen 620

waren de laatste Byzantijnse bezittingen verloren gegaan.

Moren

Volk

Toen de Romeinen in de 2de eeuw v. Chr. interesse begonnen te tonen voor de

regio, was de oorspronkelijke bevolking, zoals de Basken, (zie 2.1) al eeuwen

gemengd met de Keltische (zie 2.2). Verder waren er ook

Fenicische/Carthaagse bevolkingsgroepen te vinden, aangezien zij de

bewoners van de meeste kolonies waren. Vanaf de 2de eeuw v. Chr. werden er

ook Romeinse invloeden, aan de kust was die er al lang. In het opstandige

binnenland kwam die vooral van het legioen dat de Romeinen in centraal

Tarraconensis legerden (nabij Legio). Na de Romeinse overheersing kwamen

daar nog eens Germaanse stammen, Noord-Afrikaanse (de Moren) en veel

Joden bij.

Religie

Economie

Tarraconensis was een rijk land: vanuit het binnenland kwamen vele goederen

op de Romeinse markt terecht: hout, goud, ijzer, tin, lood, aardewerk,

vermiljoen, koper, marmer, wijn en olijfolie.

Hispania Baetica

De Romeinse provincie Hispania Baetica

.

Hispania Baetica (of gewoonweg Baetica) was de Latijnse naam van een

Romeinse provincie, gelegen in het zuiden van het huidige Spanje.

Inhoud

1 Ligging

2 Geschiedenis

o 2.1 Voor-Romeins

o 2.2 Romeins Baetica

o 2.3 Na de Romeinen

3 Beroemde Romeinen uit Baetica

4 Economie

5 Steden

Ligging

Op het Iberische schiereiland lagen er 3 Romeinse provincies: Hispania

Baetica, Hispania Lusitania ten opzichte van Baetica in het westen gelegen en

Hispania Tarraconensis, in het noorden en noordoosten. In het zuiden had

Hispania Baetica een lange kustlijn met de Middellandse Zee, die bij de Zuilen

van Hercules, de oude benaming voor de straat van Gibraltar, uitmondde in de

Atlantische Oceaan.

Geschiedenis

Voor-Romeins

Voordat Rome haar macht op de regio te pakken kreeg, was het gebied al

eeuwen eerder bewoond. In de bergachtige binnenland van wat Baetica zou

worden hadden zich verschillende Iberische stammen gevestigd en de

Keltische invloeden waren hier niet zo sterk als in het Keltiberische noorden

van Spanje.

De Griekse geschiedschrijver Herodotos verhaalde over de rijke handelsstad

Tartessos aan de monding van de Guadalquivir die in de bronstijd de handel in

de westelijke middellandse zee beheerste voordat de Feniciërs hun invloed

naar Spanje uitbreidden.

Volgens Claudius Ptolemaeus, een geograaf uit de oudheid, waren er drie

belangrijke groepen inheemse stammen. Eenderzijds waren er de machtige

Turdetani die in het westelijk deel van Baetica woonde, vooral in de vallei van

de Guadalquivir. Volgens sommige schrijvers (zoals Strabo) waren de

Turdetani afstammelingen van de eerdere bewoners van Tartessos. Andere

weerspraken dit. Daarnaast waren er de Bastetani, die rond de Almeria en in

het huidige Granada woonden. De derde groep waren de Turduli, die deels

gehelleniseerd waren en die vooral gevestigd waren in de vlaktes achter de

kust. Hun hoofdstad was Baelon. Verder gaf Ptolemaeus nog een volk aan: de

Bastuli die woonden aan de kust. Dat waren geen inheemse stammen, maar

Fenicische kolonisten die in de kolonies aan de kust woonden. Baetica was

een belangrijke handelsstreek voor de Feniciërs en de steden waren talrijk:

Gadira (het huidige Cadiz), dat op een eiland voor de Baetische kust lag; meer

naar het noordoosten lagen Cartago Nova (het huidige Cartagena) en Malaca

(het huidige Malaga).

Sommige steden in Baetica behielden hun pré-Indo-Europese benamingen

doorheen de Romeinse tijd: Granada werd door de Romeinen Eliberri,

Illiberis of Illiber genoemd en in de Baskische taal betekent "iri-berri" of "iliberri"nog altijd "nieuwe stad".

Heel de kust van Hispania, maar vooral Hispania Baetica, waren rijk aan

grondstoffen en speelde een belangrijke rol in de mediterrane handel. Daarom

toonden de Carthagers (die eigenlijk Fenicisch waren) veel interesse in de

regio. Toen de twee supermachten van het westelijke deel van de

Middellandse Zee, Carthago en Rome, met elkaar in botsing kwamen, is het

dan ook niet zo verwonderlijk dat het conflict al snel over deze streken zou

gaan.

Tijdens de Eerste Punische Oorlog (264 - 241 v. Chr.) werd er niet

rechtstreeks in Hispania Baetica gevochten, maar toen Carthago de eilanden

Sicilië, Corsica en Sardinië kwijtspeelde aan Rome, compenseerde het zijn

verlies door de kolonies in Hispania sterk uit te breiden. Hierdoor stonden de

meeste stammen in Baetica onder Carthaagse heerschappij. Lang duurde dat

echter niet, want tijdens de Tweede Punische Oorlog (218 - 204 v. Chr.) kon

Scipio Africanus tijdens zijn 4-jarige Spaanse veldtocht de meeste Fenicische

bezittingen innemen. Zo vielen de steden Baecula in 208 en Ilipa, nabij de

Guadalquivir, in 206 v. Chr..

Romeins Baetica

De nieuwe gebieden die door Scipio waren veroverd, werden door de

Romeinen in 2 provincies verdeeld. Hispania Citerior in het noorden en

Hispania Ulterior in het zuiden. Tijdens de 2de eeuw v. Chr. werd de regio

sterk geromaniseerd, maar niet alle stammen waren daar even gelukkig mee:

de Turdetani kwamen in 197 v. Chr. in opstand en de Keltiberische stammen

in Hispania Citerior volgden snel. Het koste Marcus Porcius Cato, die in 195

v. Chr. consul was geworden, veel moeite en een jaar tijd om de noordelijke

stammen te verslaan en in 194 v. Chr. werden ook de Turdetani onder de voet

gelopen. Cato keerde in datzelfde jaar nog naar Rome terug en stelde twee

praetors aan over de twee Spaanse provincies.

M. Cato

Na de opstanden bleef het in Baetica rustig, in tegenstelling tot Hispania

Citerior, waar de veroveringsoorlog bleef doorgaan tot in 19 v. Chr.

In 14 v. Chr., onder Augustus, werd het rijk gereorganiseerd. Augustus splitste

Hispania Ulterior in twee (Hispania Baetica en Hispania Lusitania) en

hernoemde Hispania Citerior tot Hispania Tarraconensis. Baetica werd vanaf

dan door een proconsul geregeerd, die voordien een praetor was geweest.

Hispania Baetica lag ver van gevaarlijke staatsgrenzen en had daarom geen

legioenen op haar grondgebied gevestigd. Doordat de provinciegouverneur

geen legers had, en daarom onschadelijk was voor de keizer in Rome, kon de

Senaat de provinciegouverneur kiezen. Indien deze toch problemen ondervond

in zijn provincie, kon hij nog altijd beroep doen op Legio VII Gemina, dat in

Hispania Tarraconensis in het noorden, permanent gevestigd was.

Hispania Baetica werd ook in vier conventi verdeeld: Gaditanus, Cordubensis,

Astigitanus en Hispalensis. Dit was een administratieve verdeling van het

gehele grondgebied, dat vooral voor juridische doeleinden werd gebruikt:

éénmaal per jaar kwamen de hoofdmannen van verschillende dorpen bijeen

onder toezicht van de proconsul om juridische aangelegenheden te bespreken.

In het late Romeinse Rijk, toen de steden het centrum van de juridische macht

werd, verloren de conventi hun bedoeling en werden ze afgeschaft.

De term conventus bleef in het later Romeinse Rijk bestaan, maar als de naam

voor een groep Romeinse burgers die woonden in een provincie en stemrecht

hadden. Zij representeerden het Romeinse volk als een soort landeigenaars.

Uit deze klasse namen de gouverneurs vaak hun medewerkers. Buiten enkele

sociale opstandjes, zoals toen Septimus Severus een aantal belangrijke

Baetische mannen en vrouwen terechtstelde, bleef de Baetische elite door de

eeuwen heen een stabiele klasse.

Baetica was rijk en sterk geromaniseerd. Daarom verleende keizer

Vespasianus aan de burgers van Hispania Baetica de Ius latii: daarmee

verkregen alle vrije burgers van Hispania Baetica het Romeinse

staatsburgerschap: een eer die de loyaliteit van de Baetische elite en

middelklasse kon veilig stellen.

Vespasianus

Na de Romeinen

Baetica bleef een Romeinse provincie tot de Vandalen en de Alanen in de 5e

eeuw Hispania binnenvielen. Zij werden kort daarop gevolgd door de

Visigoten, die er een koninkrijk stichtten. De katholieke bisschoppen van

Baetica, die sterk werden gesteund door de bevolking van Baetica, kon de

Ariaanse Visigotische koning Reccared en diens edelen bekeren.

Door een burgeroorlog in het Visigotische koninkrijk, kon de Byzantijnse

Justinianus in 554 Hispania Baetica van de Visigoten afsnoepen. Lang duurde

dat echter niet, want in 620 waren de laatste Byzantijnse bezittingen in

Hispania verloren gegaan. In de 8e eeuw stichtten de islamitische Berbers (de

Moren) uit Noord-Afrika het Kalifaat van Cordoba. Hispania Baetica werd

door de Moren herdoopt tot "Andalusië" ("land van de Vandalen" is een van

de mogelijke etymologische verklaring van Andalusië), de naam die de regio

nu nog draagt.

De 20ste eeuwse componist Manuel de Falla schreef de Fantasia Baetica voor

de piano, waarvoor hij Andalusische melodieën gebruikte.

Beroemde Romeinen uit Baetica

1. Columella, die een 12-delig essay over alle aspecten van het Romeinse

landbouwsysteem schreef, en die ook een uitgebreide kennis over de

wijnbouwcultuur had, was afkomstig uit Baetica.

2. Trajanus, de eerste keizer afkomstig uit de provincies, was geboren in

Hispania Baetica.

3. Ook Hadrianus was afkomstig uit Hispania Baetica.

Economie

Tijdens de hele Romeinse tijd was Hispania Baetica een rijke provincie (de

Romeinen noemden ze soms ook wel Baetica Felix, het gelukkige Baetica).

Een dynamisch economisch systeem heerste hier, geleid door de rijke elite (de

equites) met daaronder het gewone volk en de vrijgelatenen. Daaronder

stonden de slaven, die absoluut geen rechten hadden. De voornaamste pijlers

van de economie waren de mijnbouw van metalen zoals koper, goud en zilver.

Dit was trouwens al duizenden jaren belangrijk in dit met vele soorten ertsen

rijkbedeelde gebied zoals de geschiednis van Tartessos al aangaf. Daarnaast

was er een belangrijke wijnbouw en graancultuur naast vele andere

mediterrane producten.

Gallaecia

Gallaecia of Callaecia was de naam van een Romeinse provincie die een

gebied in het noordwesten van Hispania omvat (ongeveer tegenwoordig

Galicië in Spanje en noord Portugal). De belangrijkste en historische

hoofdstad was Bracara Augusta, het moderne Portugese Braga.

Inhoud

1 Beschrijving

2 Geschiedenis

3 Zie ook

4 Externe links

Beschrijving

De Romeinen noemden het noordwestelijk deel van het Iberisch schiereiland

Gallaecia, naar de Gallaeci (Grieks Kallaikoi) stam die de belangrijkste

vijand in het gebied was geweest. De wilde Gallaecian Kelten schreven hun

eerste geschiedenis in de 1e eeuwse Punica van Silius Italicus over de Eerste

Punische Oorlog:

Fibrarum et pennae divinarumque sagacem

flammarum misit dives Callaecia pubem,

barbara nunc patriis ululantem carmina linguis,

nunc pedis alterno percussa verbere terra,

ad numerum resonas gaudentem plauder caetras. (book III.344-7)

"Rijk Gallaecia zendt haar jeugd, wijs in de kennis van waarzeggen uit de

ingewanden van dieren door veren en vlammen, die, met hun barbaarse

gezang in hun eigen taal op de grond stampen met de ene en de andere voet in

hun ritmische dansen tot de grond trilt, en die de dit begeleiden met de sonore

caetras" (of gaethas, doedelzakken, misschien hun vroegste vermelding.)

Gallaecia als gebied werd dus door de Romeinen aangeduid voor zijn

gemengde Celtiberische cultuur, de cultuur van de castros of castrexa, de

heuvelforten van Keltische origine, zowel voor de verlokkingen van haar

goudmijnen. Deze beschaving strekte zich uit over het hedendaagse Galicië,

het noorden van Portugal, het westelijk deel van Asturië, de Bierzo, en

Sanabria.

Geschiedenis

Romeins Gallaecia als deel van Tarraconensis onder Caesar Augustus na de

Cantabrische Oorlogen 69 v. Chr.

Romeins Gallaecia onder Diocletianus 293 n. Chr.

Na de Punische oorlogen wilden de Romeinen Iberië veroveren. De stam van

de Gallaicoi 60.000 sterk volgens Paulus Orosius, stond tegenover de

Romeinse legers in 137 v. Chr. in een slag bij de rivier de Douro (Spaans

Duero, Latijn Durius), die uitliep op een grote Romeinse overwinning, en

waardoor de Romeinse proconsul Decimus Junius Brutus als held kon

terugkeren, en hij kreeg de naam Gallaicus ("overwinnaar van de Gallaicoi").

Hierna vochten de Gallaeciers in de Romeinse legioenen, tot plaatsen als

Dacia and Brittannië. Het laatste verzet van de Kelten werd onder Keizer

Octavianus in de gewelddadige Cantabrische Oorlogen tussen 26 en 19 v. Chr.

de kop ingedrukt. De weerstand was verbijsterend: liever collectieve

zelfmoord dan overgave, moeders die hun kinderen doodden alvorens

zelfmoord te plegen, gekruisigde gevangen die liederen zongen, en

gevangenopstanden die hun wachters doodden en terugkeerden naar Gallië.

Voor Rome was Gallaecia een regio die gevormd werd uit twee conventus : de

Lucensis en de Bracarensis; en deze waren duidelijk afgebakend van andere

gebieden zoals Asturica, volgens geschreven bronnen:

Legatus iuridici to per ASTURIAE ET GALLAECIAE.

Procurator ASTURIAE ET GALLAECIAE.

Cohors ASTURUM ET GALLAECORUM.

Plinius: ASTURIA ET GALLAECIA

In de 3e eeuw creëerde Diocletianus een bestuurlijke indeling die de conventus

van Gallaecia, Asturica en misschien Cluniense omvatte. Deze provincie kreeg

de naam Gallaecia omdat Gallaecia de meest bevolkte en het belangrijkste

gebied in de provincie was. In 409, toen de Romeinse macht taande, ging

Romeins Gallaecia (convents Lucense en Bracarense) door overwinningen van

de Suebi over in het Koninkrijk Gallaecia (het Galliciense Regnum

opgetekend door Hydatius en Gregorius van Tours).

In Beatus van Liébana (d. 798) duidt Gallaecia op het Christelijk deel van het

Iberisch schiereiland, terwijl Hispania het moslimdeel aanduidt. De emirs

vonden het niet nodig de bergen te veroveren die vol met legertjes zaten en

zonder wijn of olie waren.

In de tijd van Karel de Grote kwamen bisschoppen uit Gallaecia op de Raad

van Frankfurt in 794. Toen hij in Aquisgran woonde ontving hij afgezanten

van de koningen van Gallaecia (796-798) volgens Frankische kronieken.

Sancho III of Navarre in 1029 refereert aan Vermudo III als Imperator domus

Vermudus in Gallaecia.

Hispania Lusitania

Hispania Lusitania (of kortweg Lusitania) was in de oudheid een Romeinse

provincie. Het omvatte bijna heel het huidige Portugal en een deel van Spanje

(Extremadura). De provincie was genoemd naar de inwoners, de Lusitaniërs,

een volksstam van onzekere afkomst die in de regio woonde voor de komst

van de Romeinen.

Inhoud

1 Geschiedenis

o 1.1 Lusitaniërs

o 1.2 Oorlog tegen Rome

2 Steden

Geschiedenis

Lusitaniërs

Hispania Lusitania was de woonplaats van de Lusitaniërs, een stam die zich in

het gebied vestigde rond de 6e eeuw v. Chr.. Hun herkomst is onzeker, maar

de Alpen worden vaak door historici genoemd. Een door historici veel

gevolgde hypothese is, is dat toen de Kelten het Iberische Schiereiland

binnentrokken, de Lusitaniërs voor enige tijd door de Kelten onderworpen

waren. De Lusitaniërs waren echter geduchte krijgers en zij konden hun

onafhankelijkheid weer afdwingen. Deze hypothese werd voor het eerst door

Avienus gemaakt, die de Ora Maritima schreef. Hij kon zich daarbij nog

baseren op documenten uit de 6e eeuw v. Chr.. die sindsdien voor ons

definitief verloren zijn gegaan.

Hoe dan ook, de Lusitaniërs bezaten ten tijde van de Carthaagse en Romeinse

expansie het gebied dat de Romeinen later als hun provincie Lusitania zouden

zien. De kern van het Lusitanische cultuurgebied was de vallei van de Douro

en de Beira Alta. Van daaruit begon een kleine expansie naar wat nu

Extremadura is en kwamen zo in botsing met de Kelten, die een jammerlijke

nederlaag leden.

Oorlog tegen Rome

Livius vermeldt de Lusitaniërs voor de eerste keer in 218 v. Chr.; de

Lusitaniërs worden beschreven als Carthaagse huurlingen. Tegen 194 v. Chr.

was er sprake van een open oorlog tussen de Republiek Rome en de

Lusitaniërs. Na de Tweede Punische Oorlog waren de Carthaagse belangen in

Hispania Romeins geworden en konden de Romeinen zich toeleggen op de

verovering van de rest van het schiereiland.

In 179 v. Chr. overwon Lucius Postumius Albinus, een praetor, de Lusitani

(hun Latijnse naam) voor het eerst. Deze overwinning kon echter niet

voorkomen dat in 155 v. Chr. de Lusitani onder leiding van Punicus

(misschien een Carthaagse generaal) Gibraltar bereiken. Dit herhaalde zich

onder leiding van Cesarus, maar de Lusitani werden door Lucius Mummius

verslagen.

De oorlog bleef doorduren, en Servius Sulpicius Galba sloot een vals

vredesverdrag. Terwijl de Lusitani dit vierden, werden ze aangevallen door

Romeinse troepen. Overlevers van dit bloedbad werden als slaven verkocht.

Deze tactiek lokte wel een nieuwe opstand uit, onder leiding van Viriathus die

echter snel eindigde nadat deze werd vermoord door verraders. Decimus

Junius Brutus en Marius behaalden in 113 v. Chr. verdere overwinningen,

maar de Lusitani bleven zich verzetten door een guerrilaoorlog, die pas onder

Keizer Augustus helemaal werd onderdrukt.

Fantastische site (helaas in het Spaans) over alle oude Iberische

talen/inscriptie:

http://www.uned.es/geo-1-historia-antiguauniversal/TARTESSOSFUENTENTRADA.htm

Prehistorisch Portugal.

Portugal is al minstens 500.000 jaar bewoond, eerst door Neanderthalers en

later door de Homo sapiens.

Inhoud

1 Paleolithicum

2 Mesolithicum

3 Neolithicum

4 Bronstijd

Paleolithicum

Zo'n 22.000 jaar geleden, in het paleolithicum, trokken de Neanderthalers het

Iberisch schiereiland binnen en brachten ongeveer 9.000 jaar geleden de

Mousterische cultuur tot ontwikkeling. In het begin van het Jongpaleolithicum begon de eerste bewoning van Europa door de moderne mens;

het waren nomaden die uit het steppegebied in Centraal-Azië kwamen.

Ongeveer 5.000 jaar geleden was er sprake van een nieuwe immigratiegolf,

vanuit Zuid-Frankrijk. Terwijl de daarmee de Gravettian cultuur opkwam,

stierf ter zelfdertijd de Neanderthaler uit.

Mesolithicum

Het 10e millennium v. Chr. is het einde van het jonge paleolithicum en het

begin van het mesolithicum. De volken die zich op het Iberisch schiereiland

bevinden, afstammelingen van de Cro-Magnon, trekken Europa in, dat

vanwege het einde van de ijstijd weer bewoonbaar wordt. In Zuid-Frankrijk en

op het Iberisch schiereiland tot aan de monding van de Douro treft men de

Azilian cultuur aan, in de vallei van de Taag de Muge cultuur.

Neolithicum

Rond het 5de millennium v. Chr. begint het neolithicum in het Iberisch

schiereiland. Er ontwikkelt zich landbouw, en de Megalithische cultuur begint

er, die zich over heel Europa verspreidt. Later, in het 3de millennium c. Chr.

ontwikkelt zich rond het gebied waar nu Lissabon ligt de chalcolithische

cultuur van Villanova. De klokbekercultuur breidt zich uit over heel WestEuropa.

Bronstijd

Rond de 10e eeuw v. Chr. trekken de eerste golven van de urnenveldencultuur

(Proto-Kelten) het gebied binnen. Er is een bronscultuur (Indo-Europees) die

handel onderhoudt met Bretagne en de Britse eilanden. De Castro Village

cultuur komt op. In het huidige Andalusië komt de Tartessiaase gemeenschap

op

Pre-Romeins Portugal.

10e eeuw v. Chr.

Eerste contacten tussen de Feniciërs en het Iberië (langs de

Mediterraanse kust).

Ontwikkeling van Tartessos, de eerste Iberische Staat genoemd in

schrift. Tartessos was een gecentraliseerd Koninkrijk onder Fenicische

invloed dat commerciële relaties met wat nu de Algarve heet

onderhield, bewoond door de Cynetes of Cunetes, en Portugese

Estremadura.

Opkomst van steden en dorpen in de zuidelijke kustgebieden van het

westelijke Iberische schiereiland.

9e eeuw v. Chr.

Vestiging van de kolonie Carthago (in Noord Afrika) door de stad-staat

Tyrus).

Vestiging van de Fenicische kolonie Gadir (modern Cádiz) bij

Tartessos. Er zijn geen gegevens dat de Feniciërs ten westen van de

Straat van Gibraltar kwamen. De Fenicische invloed in wat nu Portugees

gebied is liep via culturele en commerciële uitwisseling met Tartessos.

Feniciërs introduceren in het Iberisch schiereiland gebruik van ijzer, het

pottenbakkerswiel, de productie van Olijfolie en Wijn.

Er wonen mensen in Olissipona (modern Lissabon en Estremadura) met

duidelijk Mediterraanse invloeden. De mythe van een Fenicische

stichting van Lissabon in de 13e eeuw v. Chr. onder de naam Alis Ubbo

("Veilige Haven") klopt niet.

8e eeuw v. Chr.

Sterke Fenicische invloed in Balsa (modern Tavira in de Algarve).

7e eeuw v. Chr.

Sterke Tartessian invloed in de Algarve.

Tweede golf van Indo-Europese migratie (Kelten van de Hallstatt

cultuur?) in Portugees gebied.

6e eeuw v. Chr.

Verval van de Fenicische kolonisatie van de Mediterraanse kust van

Iberië.

Val van Tartessos.

Begin van Griekse vestiging op het Iberische schiereiland, op de

oostelijke kust (modern Catalonië). Er zijn geen Griekse colonies ten

westen van de Straat van Gibraltar, alleen ontdekkingsreizen.

Opkomst van Carthago, dat langzaam de Feniciërs in haar vorige

kolonies verdringt.

Fenicisch beïnvloed Tavira wordt door geweld verwoest.

Culturele verschuiving in Zuid-Portugal na de val van Tartessos met een

sterk Mediterraan karakter. Dit treedt vooral in de'Alentejo en de

Algarve op, maar heeft uitbreidingen naar de Taag (de belangrijke stad

Bevipo, modern Alcácer do Sal).

Eerste vorm van schrift in het westelijk Iberisch schiereiland het

Zuidwest script (moet nog ontcijferd worden), dat duidt op sterke

Tartessiaanse invloed en gebruik van gemodificeerd Fenicisch. In deze

geschriften komt het woord Conii (gelijk aan Cunetes of Cynetes, het

volk van de Algarve, regelmatig voor.

Het gedicht Ora Maritima, door Avienus in de 4e eeuw v. Chr. en

gebaseerd op de Massilische Periplus van de 6e eeuw v. Chr., stelt dat

het hele westelijke Iberische schiereiland eens naar haar inwoners de

Oestriminis heette, die later verdreven zijn door een invasie van Saephe

of Ophis (betekent Slangen). Vanaf die tijd zou westelijk Iberia bekend

zijn als Ophiussa (Land van de Slangen). Het gedicht vertaalt misschien

de invloed van de tweede golf van Indo-Europese migraties (Kelten) in

de 7e eeuw v. Chr.. Het gedicht noemt ook verschillende andere

stammen:

De Saephe of Ophis, waarschijnlijk Hallstatt cultuur Kelten, wonen in

heel westelijk Iberia tussen de Douro en de Sado rivieren.

De Cempsi, waarschijnlijk Hallstatt cultuur Kelten, bij de monding van

de Taag en naar het zuiden tot de Algarve.

De Cynetes of Cunetes in het uiterste zuiden en in sommige steden langs

de Atlantische kust.

De Dragani, Kelten of Proto-Keltent van de eerste Indo-Europese golf,

in het berggebied van Galicië, noord Portugal, Asturië en Cantabrië.

De Lusis, misschien de eerste referentie aan de Lusitaniers, net als de

Dragani Kelten van de eerste Indo-Europese golf.

5e eeuw v. Chr.

Verdere ontwikkeling van sterke Centraal-Europese invloed.

Eerste geslagen munten en het gebruik van geld.

Ontdekkingsreizen door de Cathagers in de Atlantische Oceaan.

De Griekse historicus Herodotus van Halicarnassus noemt het woord

Iberia.

Bloei van Tavira.

4e eeuw v. Chr.

De Celtici, een nieuwe golf Kelten van de La Tène cultuur) dringen diep