Seleuciden

Een bijzondere periode uit de geschiedenis is de tijd van het opkomend Hellenisme, grofweg

zo tussen Alexander de Grote en de Romeinse keizers.

De filosofie kreeg toen zijn eerste vorm en de dynastieke problemen zijn vol oorlogen en

intriges.

In Egypte had je de Ptolemaeeen, de laatste farao’s, in Syrië de Seleuciden. Lees en geniet!

http://www.attalus.org/

http://www.seleukidempire.org/index.html

http://www.friesian.com/hist-1.htm

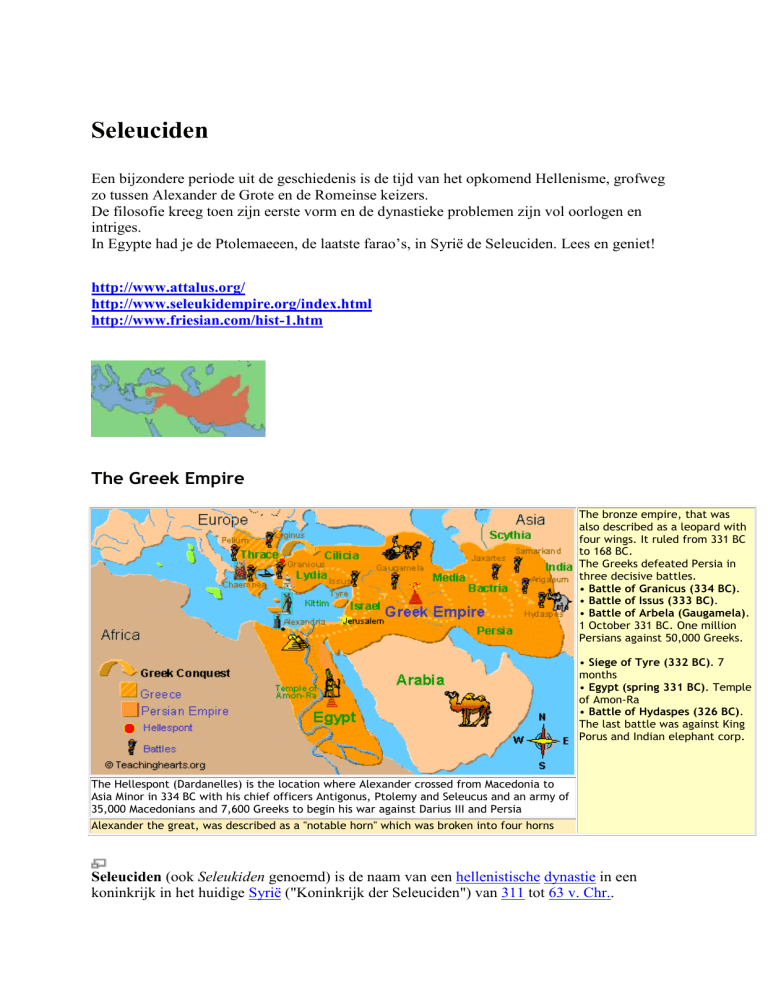

The Greek Empire

The bronze empire, that was

also described as a leopard with

four wings. It ruled from 331 BC

to 168 BC.

The Greeks defeated Persia in

three decisive battles.

• Battle of Granicus (334 BC).

• Battle of Issus (333 BC).

• Battle of Arbela (Gaugamela).

1 October 331 BC. One million

Persians against 50,000 Greeks.

• Siege of Tyre (332 BC). 7

months

• Egypt (spring 331 BC). Temple

of Amon-Ra

• Battle of Hydaspes (326 BC).

The last battle was against King

Porus and Indian elephant corp.

The Hellespont (Dardanelles) is the location where Alexander crossed from Macedonia to

Asia Minor in 334 BC with his chief officers Antigonus, Ptolemy and Seleucus and an army of

35,000 Macedonians and 7,600 Greeks to begin his war against Darius III and Persia

Alexander the great, was described as a "notable horn" which was broken into four horns

Seleuciden (ook Seleukiden genoemd) is de naam van een hellenistische dynastie in een

koninkrijk in het huidige Syrië ("Koninkrijk der Seleuciden") van 311 tot 63 v. Chr..

Het koninkrijk werd gesticht door Seleucus I Nicator (Nicator, "de Overwinnaar") (rond 358281 v. Chr.). Hij was een van de generaals van Alexander de Grote, die na diens dood in 323

v. Chr., zichzelf in Mesopotamië en de hoogvlakte van Iran vestigde, en een gebied beheerste

dat tot aan de rivier de Indus reikte. Hij stichtte Seleucia aan de Tigris (rond 305) als zijn

nieuwe hoofdstad.

Machtsgebied van Alexander de Grote

Later werd de hoofdstad van zijn dynastie echter verplaatst naar Antiochië waardoor het

machtscentrum zich verplaatste van Mesopotamië naar Syrië.

Na een korte expansie onder Antiochus de Grote raakte het rijk van de Seleuciden snel in

verval tijdens de 2e eeuw v. Chr. De Parthen slaagden erin een groot deel van het oosten over

te nemen. Eindeloze conflicten tussen twee linies van het vorstenhuis bepaalden de laatste

decennia en leidden tot de definitieve ondergang in 64 v. Chr., wanneer de Romeinen hier

door het optreden van Pompeius hun gezag vestigden.

Lijst van koningen uit het huis der Seleuciden

Seleucus I Nicator (Satraap 311 - 305 v. Chr. , Koning 305 v. Chr. - 280 v. Chr.)

Antiochus I Soter (mederegent sinds 291, regeerde 280 - 261 v. Chr.)

Antiochus II Theos (261 - 246 v. Chr.)

Seleucus II Callinicus ( 246 - 225 v. Chr.)

Seleucus III Ceraunus (of Soter) ( 225 - 223 v. Chr.)

Antiochus III de Grote (223 - 187 v. Chr.)

Seleucus IV Philopator (187 - 175 v. Chr.)

Antiochus IV Epiphanes (175 - 164 v. Chr.)

Antiochus V Eupator (164 - 162 v. Chr.)

Demetrius I Soter (162 - 150 v. Chr.)

Alexander I Balas (154 - 145 v. Chr.)

Demetrius II Nicator (145 - 138 v. Chr.)

Antiochus VI Dionysus (of Epiphanes) (145 - 140 v. Chr.?)

Diodotus Tryphon (140? - 138 v. Chr.)

Antiochus VII Sidetes (of Euergetes) ( 138 - 129 v. Chr.)

Demetrius II Nicator (opnieuw, 129 - 126 v. Chr.)

Alexander II Zabinas (129 - 123 v. Chr.)

Cleopatra Thea (126 - 123 v. Chr.)

Seleucus V Philometor(126/125 v. Chr.)

Antiochus VIII Grypus (125 - 96 v. Chr.)

Antiochus IX Cyzicenus (114 - 96 v. Chr.)

Seleucus VI Epiphanes Nicator (96 - 95 v. Chr.)

Antiochus X Eusebes Philopator (95 - 92 v. Chr. of 83 v. Chr.)

Demetrius III Eucaerus (of Philopator) (95-87 v. Chr.)

Antiochus XI Ephiphanes Philadelphus (95 - 92 v. Chr.)

Philippus I Philadelphus (95 - 84/83 v. Chr.)

Antiochus XII Dionysus (87 - 84 v. Chr.)

(Tigranes I van Armenië) (83 - 69 v. Chr.)

Seleucus VII Kybiosaktes of Philometor (70s v. Chr. - 60s v. Chr.?)

Antiochus XIII Asiaticus (69 - 64 v. Chr.)

Philippus II Philoromaeus (65 - 63 v. Chr.)

Seleucus I Nicator

http://www.mlahanas.de/Greeks/Persons2a.htm

Seleucus I (358 - 281 v. Chr.), bijgenaamd Nicator (d.i. "overwinnaar", Oud-Grieks:

Σέλευκος Νικατωρ), de stichter van het naar hem genoemde Seleucidenrijk, was aanvankelijk

veldheer onder Alexander de Grote en één der diadochen, onder wie hij doorgaat als de meest

humane en bekwame.

Na de dood van Alexander voerde hij het opperbevel over diens ruiterij. Hij bracht het in 321

tot satraap van Babylon, en in deze functie kreeg hij tijdens en als gevolg van de

diadochenstrijd het oostelijk deel van Alexanders rijk grotendeels in zijn macht. In het jaar

305 nam hij de koningstitel aan, in navolging van Antigonus I Monophthalmus van

Macedonië). Dit was het begin van de dynastie der Seleuciden, die over Syrië zou regeren tot

de Romeinen hier in 64 v. Chr. door het optreden van Pompejus hun gezag zouden vestigen.

Van de Indische vorst Chandragupta Maurya kreeg hij 500 krijgsolifanten cadeau en dit

bezorgde hem het militaire overwicht tegen Antigonus I, die hij met een coalitieleger versloeg

bij Ipsus in 301. Door deze overwinning verkreeg hij Syrië, en hij stichtte het jaar daarop aan

de rivier Orontes de stad Antiochia. Na de stichting van Antiochië richtte hij zijn aandacht

vrijwel uitsluitend op het westen van zijn rijk, en verkreeg ook de macht over het grootste

deel van Klein-Azië, door een overwinning op Lysimachus in de Slag bij Curupedium in 281

v. Chr.

Lysimachus

Antigonus I

Diadochen

De Diadochen (Grieks: Opvolgers) waren de generaals in het leger van Alexander de Grote,

die na zijn dood uiteindelijk zijn gigantische rijk overnamen en in een aantal zgn.

Diadochenrijken verdeelden.

Na Alexanders plotselinge dood op 10 juni 323 v. Chr. trachtte zijn moeder Olympias het rijk

bij elkaar te houden voor haar kleinzoon, de zoon van Alexander en Roxane. Deze was echter

nog erg jong -hij was pas na de dood van Alexander geboren- en tijdelijk nam Alexanders

broer Philippus Aridaeus daarom het koningschap waar. Philippus was echter niet erg

geschikt voor het koningschap en daarom werden de generaals van Alexander steeds

machtiger.

Ph. Arideus

Alexander IV en Roxane

De onderlinge concurentie tussen de generaals leiden tot verschillende oorlogen waarbij de

coalities veel wisselden. Tijdens deze oorlogen geraakte de dynastie van Alexander steeds

meer op de achtergrond. Uiteindelijk werden zijn vrouw, moeder en kind vermoord. De

oorlogen duurden omgeveer 40 jaar (322 v. Chr. tot 281 v. Chr). Belangrijken gebeurtenissen

in deze periode:

323 dood van Alexander de Grote

323 Antipater slaat in Griekenland een opstand tegen het Macedonische gezag neer

320 vermoording van Perdiccas, de rijksregent

317 vermoording van Alexander's broer Philippus

316 vermoording van Olympias

309 vermoording van Alexander's zoon, Alexander IV, en vrouw Roxane

306 Antigonas Monopthalos en Demetrius Poliocertes veroveren Cyprus en nemen de

koningstitel aan

301 Slag bij Ipsus, Antigonas Monopthalos sneuvelt

281 Lysimachus sneuvelt in de slag bij Corupedium

Na deze oorlogen was het idee van de eenheid van het rijk verdwenen en hadden zich vaste

territoria gevormd.

Egypte met Palestina, Cyprus en stukken van Klein-Azië en de Aegeische zee onder

de dynasty van de Ptolemaeën

Klein Azie, Syrië, Mesopotanië en Perzië onder de Seleuciden

Macedonië en Griekenland onder de Antigoniëen

Behalve deze gebieden waren er nog diverse andere gebieden die tot het rijk van Alexander de

Grote hadden gehoord, bijv. Epirus

Pyrrhus van Epirus

Alle rijken werden uiteindelijk door de Romeinen veroverd. Egypte als laatste in 30 v. Chr.

Hellenistische rijken

Demetrius Poliocertes

Door uitgebreide stedenstichtingen verspreidde Seleucus de Griekse cultuur in een oosterse

omgeving. Hij was ook de enige van de diadochen die zijn oosterse echtgenote, Apame, niet

verstootte, maar naast haar trad hij ook in het huwelijk met de veel jongere Stratonice, de

dochter van Demetrius Poliorcetes. Later stond hij deze bereidwillig af aan zijn zoon

Antiochus I, sedert 293 ook zijn mederegent en opvolger. Bij een poging om ook Macedonië

en Thracië in te lijven werd hij door Ptolemaeus Ceraunus, zoon van Ptolemaeus I, gedood.

Kaart

Ong. 280 v. Chr.

Antiochus I Soter

Antiochus I (324 - 261 v. Chr.), bijgenaamd Sotèr (d.i. "redder" of "verlosser", Grieks

Αντίοχος Σωτήρ), was koning van het hellenistische Seleucidenrijk (Syrië) van 280 tot aan

zijn dood.

Hij was de zoon van Seleucus I Nicator, en stond aan het hoofd van diens ruiterij in de Slag

van Ipsus in 301 v. Chr. Toen uitlekte dat Antiochus smoorverliefd was op Stratonice, de

jeugdige echtgenote van zijn vader, stond deze haar probleemloos aan hem af.

In 280 beklom hij de troon, en besloot af te zien van zijn vaders veroveringsplannen met het

oog op het Westen. Hij sloot een vredesverdrag met Antigonus II Gonatas van Macedonië en

huwelijkte aan deze zijn zuster uit. Met dit huwelijk legde hij de grondslag voor een eeuw van

vriendschap met Macedonië.

Antigonus II

Zijn bijnaam dankte hij aan zijn overwinning in de Slag der Olifanten in 276, tegen de

Galaten die zijn rijk waren binnengevallen. In Klein-Azië werkte Pergamon zich van zijn rijk

los onder Eumenes I, tegen wie hij in 262 een nederlaag leed.

Pergamon

Eumenes I

Apame

Antiochus I geldt als de voornaamste stichter van Griekse steden in het Oosten na Alexander

de Grote.

Antiochus II

Antiochus II Theos (286 — 246 v. Chr.) (soms ook Antiochos II Theos gespeld) was koning

van het Rijk der Seleuciden (Syrië) (261-246 v. Chr.). Zijn vader was koning Antiochus I

Soter en zijn moeder de Macedonische prinses Stratonice II.

Toen hij aan de macht kwam was het rijk in oorlog met de Ptolemaeën onder koning

Ptolemaeus II van Egypte. In 258 v. Chr. wist hij Timarchus af te zetten, een pro-Egyptische

tiran van Milete. Het volk van Milete kende hem daarom de titel "God" (Theos) toe.

In ongeveer 250 v. Chr. eindigde de oorlog en Antiochus bezegelde dit door te trouwen met

Berenice, dochter van Ptolemaeus II Philadephus na scheiding van zijn eerste vrouw Laodice.

Ofschoon Berenike hem wel een kind schonk, ging het huwelijk mis en in 246 v. Chr. haalde

Laodice haar man weer terug bij haar. Datzelfde jaar stierf de koning. Geruchten gingen dat

hij door Laodice vergiftigd was zodat haar oudste zoon Seleucus II Callinicus aan de macht

kon komen.

Antiochus II

Seleucus II

Berenice I

Seleucus II Callinicus

Seleucus II (tussen 265 en 260 - 225 v. Chr.), bijgenaamd Callinicus (d.i. "een mooie

overwinning behalend"), was koning van het hellenistische Seleucidenrijk (Syrië) van 246

tot aan zijn dood.

Hij was de oudste zoon van Antiochus II en diens eerste echtgenote Laodice, en beklom de

troon in 246. Tijdens zijn regering gingen voor het Seleucidenrijk aanzienlijke gebiedsdelen

verloren: in het oosten maakten de satrapieën Parthië en Bactrië zich los, terwijl in Klein-Azië

het koninkrijk Pergamon tot stand kwam en zich uitbreidde tot aan de Taurus. Ook in een

oorlog tegen Ptolemaeus III van Egypte gingen gebieden in Klein-Azië verloren: zelfs

Seleucia Pieria, de havenstad van Antiochia, werd door Ptolemaeus bezet en bleef daarna

gedurende 25 jaar in Egyptische handen. Alsof dat nog niet genoeg was profiteerde Seleucus'

jongere broer Antiochus Hiërax van diens langdurige veldtochten om zichzelf als autonoom

heerser in Klein-Aziê te gedragen, hierbij gesteund door zijn moeder.

Antiochus Hierax

Antiochus bracht zijn broer in 239 v. Chr. nabij Ancyra een zware nederlaag toe, en kon pas

tussen 236 en 228 geleidelijk bedwongen worden, en dan nog door Attalus I van Pergamon.

Seleucus II had twee zonen, zijn opvolgers Seleucus III en Antiochus III, en twee dochters.

Hij overleed in 225 als gevolg van een val van zijn paard.

Attalus I

Seleucus III Ceraunus

Seleucus III, bijgenaamd Ceraunus (d.i. "bliksem"), was koning van het hellenistische

Seleucidenrijk (Syrië) van 225 tot 223 v. Chr..

Hij was de oudste zoon van Seleucus II Callinicus. Over zijn kortstondige regering valt

weinig meer te zeggen dan dat hij, om verder onbekende redenen, door hovelingen werd

vergiftigd tijdens een veldtocht tegen Attalus I van Pergamon.

Seleucus III

Antiochus III de Grote

Antiochus III (241 - 187 v. Chr.), bijgenaamd de Grote, was koning van het hellenistische

Seleucidenrijk (Syrië) van 223 tot aan zijn dood. Hij wordt beschouwd als de belangrijkste

vorst uit de dynastie na Seleucus Nicator, energiek en dapper, verbeten in het nastreven van

een vooropgesteld doel, maar ook gewetenloos en wreed, zelfs tegenover zijn familieleden.

Antiochus III was de tweede zoon van Seleucus II. Toen hij in 223 de troon besteeg had hij

onmiddellijk af te rekenen met interne moeilijkheden, veroorzaakt door separatistische

bewegingen in de gebiedsdelen Bactrië en Parthië.

Ong. 190 v. Chr.

Zijn beleid wordt gekenmerkt door een streven naar gebiedsuitbreiding. Na enkele

tegenslagen in Syrië en Palestina tegen zijn rivaal Ptolemaeus IV Philopator, richtte hij zijn

volle aandacht naar het Aziatische binnenland. Hij ondernam een veldtocht naar het oosten

die hem tot in Arabië en India bracht, een prestatie die hem de bijnaam de Grote bezorgde.

Hij won aldus Armenië en consolideerde zijn gezag in Bactrië en Parthië. In 206 moest hij

toch een nederlaag verwerken tegen de Parthen in de vallei van de Kaboel. Antiochus wou

zijn soevereiniteit aan hen opleggen. De Parthische koning Arsaces II mocht wel zijn

koninklijke waardigheden behouden.

Arsaces II

Philippus V

Na deze jaren van succes kwam hij in het westen in conflict met de Romeinen, toen hij in 202

v. Chr. na de nederlaag van zijn bondgenoot Philippus V van Macedonië zoveel mogelijk van

diens gebied wilde annexeren. Vooral zijn invallen (196 v. Chr.) op Europese bodem, met de

bedoeling Thracië en Griekenland te veroveren, schoten bij de Romeinen in het verkeerde

keelgat. Ook verleende hij asiel aan Hannibal (196), om met diens hulp Italië binnen te vallen,

wat echter mislukte. Op verzoek van de Aetolische Bond stak hij daarna als "bevrijder" naar

Griekenland over, maar werd verslagen bij de Thermopylae in 191;

Thermopylae

teruggekeerd naar Azië werd hij nog eens bij Magnesia verslagen door Lucius Cornelius

Scipio Asiaticus. Na deze zware nederlagen, zag hij zich in 188 door de Vrede van Apamea

gedwongen afstand te doen van het gehele westelijke deel van zijn rijk; bovendien legden de

Romeinen hem een enorme oorlogsschatting op en moest hij zijn krijgsvloot en zijn

strijdolifanten uitleveren. Dit betekende het einde van Syrië als Middellandse-Zeemacht, maar

in continentaal Azië zou het nog een rol van betekenis blijven spelen.

Hannibal

Antiochus III

Antiochus III werd in 187 v. Chr. door de bevolking van Elymaïs (ten zuiden van de

Kaspische Zee) vermoord bij de plundering van een plaatselijke tempel van Baäl.

Antiochus III

Seleucus IV Philopator

Seleucus IV, bijgenaamd Philopator (d.i. "die van zijn vader houdt"), was koning van het

hellenistische Seleucidenrijk (Syrië) van 187 tot 175 v. Chr..

Hij was de tweede zoon en opvolger van Antiochus III de Grote, en al tijdens het leven van

zijn vader onderkoning van Thracië. In 190 v. Chr. belegerde hij tevergeefs het met de

Romeinen verbonden Pergamon, en het volgende jaar voerde hij in de Slag bij Magnesia het

bevel over de linker vleugel van Antiochus’ leger tegen de Romeinen. Als koning probeerde

Seleucus IV zich stipt te houden aan de bepalingen van de Vrede van Apamea, waarbij de

Seleuciden elke politieke activiteit in westelijke richting was ontzegd. Om aan de hoge

krijgsschatting te kunnen voldoen, liet hij zijn raadsheer Heliodorus zware belastingen

opleggen aan de joden, hetgeen ernstige conflicten veroorzaakte.

Seleucus IV werd in 175 door deze Heliodorus vermoord.

Seleucus IV

Antiochus IV

Antiochus IV Epiphanes

Antiochus IV Epiphanes (Epiphanes is Grieks voor glorieus) (c. 215 - 163 v. Chr.),

eigenlijke naam Mitrades was van 175 tot 163 v.Chr. koning van de hellenistische

Seleuciden.

Hij was de zoon van Antiochus III de Grote en de broer van Seleucus IV Philopator. Het

gebied van de Seleuciden besloeg toen een groot gebied van het Midden-Oosten, met als

kerngebied het huidige Syrië. Ook Palestina, de Libanon en delen van het huidige Irak

maakten deel uit van zijn rijk.

Hij voerde diverse oorlogen tegen de rivaliserende Ptolemaeën in Egypte, die hij bijna wist te

verslaan. Ingrijpen van de Romeinen, die met hun vloot naar Alexandrië waren overgestoken,

dwong Antiochus echter onverrichter zake terug te keren naar Syrië.

In 168 v. Chr. beval hij om het altaar van Baäl Hasjamaïm (het Syrische equivalent van Zeus)

op te zetten in de joodse tempel te Jeruzalem. De Joodse priester Mattathias en zijn zoon

Judas Makkabeüs leidden de furieuze joden in hun opstand tegen de Seleuciden. Antiochus,

woedend over het verzet van de joden, voerde persoonlijk zijn leger aan en liet duizenden

joden ombrengen. Voor zijn wreedheid noemden de joden hem alsnel Antiochus Epimanes

(grieks voor de gek). Antiochus overleed aan een ziekte tijdens het hoogtepunt van de strijd.

Judas sneuvelde in de strijd, maar zijn broer Simon wist, zo'n twee decennia na de dood van

Antiochus IV, uiteindelijk onafhankelijkheid voor de Joodse staat te verkrijgen. Hij stichtte de

Hasmoneese dynastie, die tot 63 v. Chr. in Judea aan de macht zou blijven.

Na de dood van Antiochus IV werd het rijk van de Seleuciden lange tijd door interne twisten

verscheurd wat een verklaring kan zijn voor de uiteindelijk geslaagde opstand van de joden.

Antiochus IV werd opgevolgd door Antiochus V Eupator, die slechts twee jaar regeerde.

Antiochus V

Antiochus V Eupator

Antiochus V (ca. 173 - 162 v. Chr.), bijgenaamd Eupator (d.i. "[zoon] van een edele

vader"), was koning (onder voogdij van Lysias) van het hellenistische Seleucidenrijk (Syrië)

van 164 tot aan zijn dood.

Hij was een zoon van Antiochus IV Epiphanes en een jaar of negen toen hij koning werd. De

onderdanigheid van het hof jegens de Romeinen ergerde de Griekse steden in Syrië dusdanig

dat de Romeinse gezant Gnaeus Octavius (consul in 165 v. Chr.) in Laodicea vermoord werd

(162 v. Chr.). Na een kortstondige regering van twee jaar werd Antiochus zelf vermoord door

Demetrius, de zoon van Seleucus IV. Hiermee begon een tijdperk van dynastieke strijd die

een tijd van verval inluidde.

Demetrius I Soter

Demetrius I (Grieks Δημήτριος Σωτήρ) (187 – 150 v. Chr.), bijgenaamd Soter (d.i.

Verlosser), was koning van het hellenistische Seleucidenrijk (Syrië) van 162 tot aan zijn

dood.

Hij was de tweede zoon van Seleucus IV, en omdat hij als politiek gijzelaar in Rome werd

vastgehouden zag hij aanvankelijk het koningschap aan zijn neus voorbijgaan ten voordele

van zijn oom Antiochus IV (175 – 164 v. Chr.) en daarna van zijn neef Antiochus V (164 –

162 v. Chr.). Hij wist echter in 162 te ontsnappen en zijn rechtmatige plaats op de troon te

heroveren. Hij versloeg in het Oosten de rebellerende generaal Timarchus en onderwierp in

Palestina de opstandige joden.

Zijn kwaliteiten als heerser maakten hem als vijand geducht bij de naburige grootmachten,

waardoor hij ook de achterdocht van de Romeinen wekte, ook al had de Romeinse senaat in

160 zijn rechten op de troon erkend.

Demetrius I sneuvelde in de strijd tegen een troonpretendent, Alexander Balas, die beweerde

een jongere broer van Antiochus V te zijn, en door de koningen van Pergamon en Egypte was

omgekocht.

Alexander Balas

Alexander I (Grieks Αλέξανδρος), bijgenaamd Balas, was koning van het hellenistische

Seleucidenrijk (Syrië) van 150 tot aan zijn dood in 145 v. Chr.).

Hij beweerde een jongere zoon van Antiochus IV te zijn, en verkreeg in 150 de troon van het

Seleucidenrijk na de nederlaag en de dood van zijn voorganger Demetrius I. Hij was een

marionet in de handen van de koningen van Pergamon en Egypte, en als koning totaal

incompetent, maar hij genoot wel de volle steun van de Romeinse Senaat, omdat men te

Rome een heropleving van de macht der Seleuciden vreesde indien de rechtmatige opvolger

van Demetrius I de troon zou beklimmen.

Aan de regering van Alexander Balas kwam een einde toen hij met geweld verdreven werd en

daarbij omkwam. Zijn bewind kan gezien worden als het begin van een periode van

burgeroorlogen die de desintegratie van het Seleucidenrijk in de hand hebben gewerkt.

Demetrius II Nicator

Demetrius II (ca. 161 - 125 v. Chr.), bijgenaamd Nicator (d.i. Overwinnaar, Grieks

Δημήτριος Νικατωρ), was koning van het hellenistische Seleucidenrijk (Syrië), eerst van 145

tot 141 en vervolgens van 129 v. Chr. tot aan zijn dood.

Hij was de oudste zoon van Demetrius I Soter en besteeg de troon van zijn vader in 145, na de

uitdrijving van zijn voorganger, de pretendent Alexander Balas. Hij werd tijdens een oorlog

tegen de Parthen in 141 door dezen gevangen genomen en verkreeg pas zijn vrijlating in 129,

waarna hij opnieuw zijn plaats op de troon innam. In de tussentijd had zijn broer Antiochus

VII het regentschap waargenomen.

Het bewind van Demetrius II is kenmerkend voor de moeilijkheden waarmee de laatste

Seleuciden af te rekenen hadden. Hij moest zijn koninkrijk veroveren op een eerste

pretendent, verloor vrijwel onmiddellijk een deel ervan aan een tweede, en werd uiteindelijk

vermoord na het verlies aan een derde van wat hem nog restte.

Antiochus VI Dionysus (of Epiphanes) (145 - 140 v. Chr.?)

Diodotus Tryphon (140? - 138 v. Chr.)

Antiochus VII Sidetes (of Euergetes) ( 138 - 129 v. Chr.)

Antiochus, Demetrius's younger brother is proclaimed King and marries

(you've guessed it) Cleopatra Thea. He defeats Tryphon. He then moves on Jerusalem and

ends (for the moment) Jewish independence. By 130 BCE he is ready to take on Parthia and

reconquers Babylonia. The desperate Parthian King releases Demetrius Nicator (bad move)

and stirs revolt amongst Antiochus' new conquests who do not find Seleucid taxes to their

liking (good move). Antiochus is completely wrong footed by the revolt and is caught,

heavily outnumbered, by the Parthian main army and killed. The Parthian king immediately

sends cavalry to recapture Demetrius but too late.

Demetrius II Nicator (opnieuw, 129 - 126 v. Chr.)

Demetrius arrives in Syria at the same time as news of Antiochus' death and

regains both his throne and his wife Cleopatra Thea. (Cleopatra has however taken the

precaution to send her son by Sidetes, Antiochus, to Cyzicus in Asia Minor.) After a botched

invasion of Egypt by Demetrius, Ptolemy Euergetes discovers a son of Balas known as

Antiochus Zabinas. (Is he really the son of Balas? Does anyone care?) Zabinas quickly gains

control of the inland region once held by Tryphon and Syria is again divided. Finally

Demetrius is defeated outside Damascus and retreats to Ptolemais only to find the gates

closed against him by his wife Cleopatra. He takes a ship and is killed on Cleopatra's orders.

Seleucus V Philometor

Seleucus V, bijgenaamd Philometor (d.i. "die van zijn moeder houdt"), was kortstondig

koning van het hellenistische Seleucidenrijk (Syrië) in 126/125 v. Chr..

Hij was een zoon van Demetrius II en diens echtgenote Cleopatra Thea, een dochter van

Ptolemaeus VI van Egypte. Na de dood van zijn vader nam hij in 125 bezit van de troon, maar

dat was tegen de zin van zijn moeder, die hem dan ook kort daarop liet vermoorden.

Antiochus VI

Alexander II Zabinas (129 - 123 v. Chr.)

123: Alexander is defeated, captured, and executed

Cleopatra Thea (126 - 123 v. Chr.)

Cleopatra decides to rule in her own right and Selecus's the eldest son of

Demetrius is killed when he is foolish enough to put forward his claim. As a sop to those

unaccustomed to female rule she associates her rule with her son the pliable Antiochus

Grypus (hooknosed). Zabinas is defeated by Grypus. Antiochus proves to be less and less

pliable. Things come to a head when Cleopatra offers a cup of wine to Antiochus when he has

returned from the hunt. As this is most definitely not her habit Antiochus has a hunch this is

not maternal concern. He insists she drink the wine. She drinks. She dies.

Seleucus V Philometor(126/125 v. Chr.)

Seleucus, who must be somewhere between 15 and 20 years old, tries to become sole ruler,

but is killed; our sources blame Cleopatra

Antiochus VIII Grypus (125 - 96 v. Chr.)

Grypus (ie hook nose) demonstrates the superiority of male rule by spending his time feasting

at Daphne and writing verses on poisonous snakes.

In 116 Antiochus, the son of Sidetes who Cleopatra Thea sent to Cyzicus so as to save him

from Demetrius, arrives in Syria to make a play for the throne. This is helped by the arrival of

Cleopatra a Ptolemid princess who decided to go adventuring after she fell out with her

mother the Queen and who has acquired an army on the way. Cleopatra marries Antiochus

(known as Cyzicenus). As Cyzicenus's half brother Grypus's wife is Tryphaena who is

Cleopatra's sister this gives the civil war an extra incestuous twist. Antioch as usual is held by

the rebel forces of Cyzicenus. Grypus moves on Antioch while Cyzicenus has left it in the

hands of Cleopatra. Antioch falls.

Tryphaena demands the death of Cleopatra. Gryphus refuses. Convinced this is a sign of a

secret desire on the part of Grypus for Cleopatra, she sends troops to the sanctuary in Daphne

where Cleopatra has taken refuge. Cleopatra hangs on to the image of Artemis with such

desperation that the soldiers cannot break her hold so instead the cut through her wrists.

Cleopatra's death is soon avenged when Tryphaena falls into the hands of Cyzicenus and is

executed.

96: Natural death; in order to put an end to the civil war, his wife marries Antiochus IX.

However, a son of Antiochus VIII, Seleucus, continues his father's rule.

Antiochus IX Cyzicenus (114 - 96 v. Chr.)

Antiochus IX and Ptolemy IX Soter support the Samarians against the Hasmonaean king John

Hyrcanus of Judaea

Rome intervenes for the Jews, and against the Samarians and Antiochus IX

103: Antiochus VIII marries to Cleopatra V Selene (daughter of Ptolemy VIII Euergetes

Physcon)

Cleopatra V

S

96: Natural death of Antiochus VIII; his wife marries Antiochus IX, who is now

within reach of reuniting the Seleucid Empire

However, the son of Antiochus VIII, Seleucus VI Epiphanes Nicator, continues the

rule of his father

Early 95: In this struggle, Antiochus IX is defeated and killed

Late 95: a son of Antiochus IX, Antiochus X Eusebes, defeats Seleucus

Disintegration 96-83 BCE

Grypus is murdered by his minister Heracleon who proclaims himself King. However

Grypus's eldest son, Seleucus, inherits most of his father realm with Heracleon retaining a

small principality round Beroea. Seleucus marches on Cyzicenus and kills him in battle.

Cyzicenus' son Antiochus Eusebes is proclaimed King and in turn defeats Seleucus who flees

to Cilicia and establishes himself in Mopsuhestia. The people of Mopsuhestia, unable to

support a King's lifestyle rebel and Seleucus dies in his burning palace. Philip and Antiochus,

the brothers of Seleucus avenge themselves on Mopsuhestia and then march on Antioch

where they are defeated and Antiochus rides his horse into the Orontes and is drowned. A

fourth son of Grypus, Demetrius arrives, backed by Ptolemid troops, and establishes himself

in Damascus. What follows is a period of confused fighting that the historical records do not

do justice. Seleucid "Kings" are now little more than local barons.

Seleucus VI Epiphanes Nicator (96 - 95 v. Chr.)

Antiochus X Eusebes Philopator (95 - 92 v. Chr. of 83 v. Chr.)

It is not clear when the reign of Antiochus X Eusebes came to an end. Perhaps it was in

92, when the Parthians invaded the remains of the Seleucid Empire; alternatively, his

reign was terminated by king Tigranes II the Great in 83.

Demetrius III Eucaerus (of Philopator) (95-87 v. Chr.)

Demetrius intervenes in the Hasmonaean kingdom, against king Alexander Jannaeus.

88: Demetrius and his twin brother Philip start to quarrel.

87: Demetrius is being captured by the Parthian king Mithradates III; he dies in

captivity.

Antiochus XI Ephiphanes Philadelphus (95 - 92 v. Chr.)

92: After a brief reign, Antiochus XI Epiphanes is defeated and killed by Antiochus X

Eusebes of the southern branch. He is unable to overcome the two Seleucids in Damascus.

Philippus I Philadelphus (95 - 84/83 v. Chr.)

83: King Tigranes II the Great of Armenia adds the remains of the Seleucid Empire to his

realm; Philip remains as ruler in Cilicia.

Antiochus XII Dionysus (87 - 84 v. Chr.)

In 84, Antiochus is defeated and killed by the Nabataean Arabs

(Tigranes I van Armenië (83 - 69 v. Chr.)

Tigranes moves into Syria. A faction in Antioch invites him in. Magadates, Tigranes'

governor sits in the Palace in Antioch. The Syrians are soon unhappy with Armenian rule but

Tigranes is not so easy to get rid of as a Seleucid prince. Only a couple of isolated cities still

recognize Seleucid rule (notably Seleucia). But Tigranes is foolish enough to annoy the

Romans and Tigranes is defeated by Lucullus

Seleucus VII Kybiosaktes of Philometor (70s v. Chr. - 60s v.

Chr.?)

Antiochus XIII Asiaticus (69 - 64 v. Chr.)

64: Pompey annexes Syria as province of the Roman Empire and dethrones Antiochus; he

was murdered.

Pompejus

Philippus II Philoromaeus (65 - 63 v. Chr.)

Philip II Philoromaeus continues to rule in Cilicia.

58: Fall of Ptolemy XII Auletes, king of Egypt. Philip tries to obtain the Ptolemaic throne by

marrying Berenice IV, but the Roman governor of Syria, Aulus Gabinius, prevents this.

Berenice IV

Aulus Gabinius

Rome takes over

A son of Antiochus Eusebes establishes himself in Antioch with Lucullus' approval but soon

being challenged Philip son of Philip, son of Grypus. Both are however little more than tools

in the ambitions of minor Arab chieftains. Pompeus arrives and decides to establish Syria as a

Roman Province.

Why did the Seleucid Empire self-destruct?

The Romans did not conquer the Seleucid Empire. After the defeat at Magnesia the empire

was still strong. The Pergamonese and Ptolemids stirred things up for their own ends but

essentially the Seleucids destroyed themselves in bitter and, by the end, continuous civil war.

Why?

Bevan's explanation is folly. The Seleucids had the bad luck to be produce a bunch of tyrants

who squandered the fine empire they inherited from illustrious ancestors. Peter Green's

explanation goes deeper but is essentially the same (though unlike Bevan he regards the

Empire as flawed from the start).

"If the 'degenerate' has any meaning at all the later Seleucids and Ptolemids were

degenerate: selfish, greedy, murderous, weak, stupid, vicious,sensual, vengeful....

In both dynasties we also find the cumulative effect of centuries of ruthless exploitation: a

foreign elite, with no long term economic insight, aiming at little more than the immediate

profits and dynastic self perpetuation, backed (for their own ends) by shrewd local and

foreign businessmen and always able to count on a mercenary army when resentment reached

boiling point."

Peter Green: Alexander to Actium p555

Tot zover dan dus maar!

Seleucia

Seleucia

Location of the city of Seleucia, modern Iraq

Seleucia (Greek: Σελεύκεια) was one of the great cities of the world during Hellenistic and

Roman times. It stood in Mesopotamia, on the west bank of the Tigris River, opposite the

smaller town of Opis (later Ctesiphon).[1]

Contents

1 History

2 Archaeology

3 Notes

4 References

5 External links

History

Seleucia, as such, was founded in about 305 BC, when an earlier city was enlarged and

dedicated as the first capital of the Seleucid Empire by Seleucus I Nicator. Seleucus was one

of the generals of Alexander the Great who, after Alexander's death, divided his empire

between them.[1] Although Seleucus soon moved his main capital Antioch, in northern Syria,

Seleucia became an important center of trade, Hellenistic culture, and regional government

under the Seleucids. Standing at the confluence of the Tigris River with a major canal from

the Euphrates, Seleucia was placed to receive traffic from both great waterways. During the

3rd and 2nd century BC, it was one of the great Hellenistic cities, comparable to Alexandria,

in Egypt, and greater than Syrian Antioch.

necropolis

Polybius (5,52ff) uses the Macedonian peliganes for the council of Seleucia, which implies a

Macedonian colony, consistently with its rise to prominence under Nicator; Pausanias (1,16)

records that Seleucus also settled Babylonians there. Archaeological finds support the

presence of a large population not of Greek culture.

In 141 BC, the Parthians under Mithridates I conquered the city, and Seleucia became the

western capital of the Parthian Empire. Tacitus described its walls, and mentioned that it was,

even under Parthian rule, a fully Hellenistic city. Ancient texts say that the city had 600,000

people, and was ruled by a senate of 300 people. It was one of the largest cities in the Western

world; only Rome and Alexandria were more populous.

In 55 BC, a battle fought near Seleucia was crucial in establishing dynastic succession of the

Arsacid kings. In this battle between the reigning Mithridates III (supported by a Roman army

of Aulus Gabinius, governor of Syria) and the previously deposed Orodes II, the reigning

monarch was defeated, allowing Orodes to reestablish himself as king.

In about 41 BC, Seleucia was the scene of a massacre of around 5,000 Babylonian Jewish

refugees (Josephus, Ant. xviii. 9, § 9).[2]

In 117 AD Seleucia was burned down by the Roman Emperor Trajan during his conquest of

Mesopotamia, but the following year it was ceded back to the Parthians by Trajan's successor,

Hadrian, then rebuilt in the Parthian style. It was finally destroyed by the Roman Empire in

164.

Lucius Verus (161-169)

Over sixty years later a new city, Veh-Ardashir, was built on the site by Ardashir I (ruled

226–241), founder of the Sassanid dynasty. This city eventually faded into obscurity and was

swallowed by the desert sands, perhaps abandoned after the Tigris shifted its course.

The site of Seleucia was rediscovered in the 1920s by archaeologists looking for Opis[3]. It is

now under a suburb of Baghdad, about 18 miles south of the city proper

Antakya

Antakya (Arabic: ان طاك ية, Greek: Ἀντιόχεια Antiókheia or Αντιόχεια Antiócheia) is the seat

of the Hatay Province in southern Turkey, near the border with Syria. In ancient times the

city was known as Antioch and has historical significance for Christianity, being the place

where the followers of Jesus Christ were called Christians for the very first time. The city and

its massive walls also played an important role during the Crusades.

Antioch

Antioch on the Orontes (Greek: Αντιόχεια η επί Δάφνη, Αντιόχεια η επί Ορόντου or

Αντιόχεια η Μεγάλη; Latin: Antiochia ad Orontem; also Antiochia dei Siri, Great Antioch

or Syrian Antioch) was an ancient city on the eastern side (left bank) of the Orontes River,

located on the site of the modern city of Antakya, Turkey.

Founded near the end of the 4th century BC by Seleucus I Nicator, one of Alexander the

Great's generals, Antioch was destined to rival Alexandria as the chief city of the nearer East

and to be the cradle of gentile Christianity. It was one of the four cities of the Syrian

tetrapolis.

History

Antiquity

See Antioch for the long, rich history of this area in the ancient and classical periods, dating

back to the Calcolithic era of 5000 BC (as revealed by excavations of the mound of TellAçana among others). Subsequent rulers of the area include Alexander the Great, who after

defeating the Persians in 333 BC followed the Orontes south into Syria. The city of Antioch

was founded in 300 BC, after the death of Alexander, by the Seleucid King Antiochus Soter,

and went on to play an important part in the history as one of the largest cities in the Roman

Empire and Byzantium, a key location of the early years of Christianity, the Antiochian

Orthodox Church, the rise of Islam and The Crusades.

Prehistory

The settlement of Meroe pre-dated Antioch. A shrine of Anat, called by the Greeks the

"Persian Artemis," was located here. This site was included in the eastern suburbs of Antioch.

There was a village on the spur of Mount Silpius named Io, or Iopolis. This name was always

adduced as evidence by Antiochenes (e.g. Libanius) anxious to affiliate themselves to the

Attic Ionians--an eagerness which is illustrated by the Athenian types used on the city's coins.

At any rate, Io may have been a small early colony of trading Greeks (Javan). John Malalas

mentions also an archaic village, Bottia, in the plain by the river.

Foundation by Seleucus I

Alexander the Great is said to have camped on the site of Antioch, and dedicated an altar to

Zeus Bottiaeus, which lay in the northwest of the future city. This account is found only in the

writings of Libanius, a 4th century AD orator from Antioch, and may be legend intended to

enhance Antioch's status. But the story is not unlikely in itself.[1]

After Alexander's death in 323 BC, his generals divided up the territory he had conquered.

Seleucus I Nicator won the territory of Syria, and he proceeded to found four "sister cities" in

northwestern Syria - Antioch, Seleucia Pieria, Apamea and Laodicea-on-the-Sea - all named

by Seleucus for members of his family. It is said of Seleucus I Nicator that "few princes have

ever lived with so great a passion for the building of cities. He is reputed to have built in all

nine Seleucias, sixteen Antiochs, and six Laodiceas".[2]

Seleucus founded Seleucia Pieria, the port city near Antioch, in 300 BC on a site through

ritual means. An eagle, the bird of Zeus, had been given a piece of sacrificial meat and the

city was founded on the site to which the eagle carried the offering.

Seleucus next founded Antioch on a site chosen through the same means, in the twelfth year

of his reign. Although Seleucia Pieria was at first the Seleucid capital city in northwestern

Syria, Antioch soon rose above it to become the Syrian capital.

Hellenistic age

The original city of Seleucus was laid out in imitation of the "gridiron" plan of Alexandria by

the architect Xenarius. Libanius describes the first building and arrangement of this city (i. p.

300. 17). The citadel was on Mt. Silpius and the city lay mainly on the low ground to the

north, fringing the river. Two great colonnaded streets intersected in the centre. Shortly

afterwards a second quarter was laid out, probably on the east and by Antiochus I, which,

from an expression of Strabo, appears to have been the native, as contrasted with the Greek,

town. It was enclosed by a wall of its own. In the Orontes, north of the city, lay a large island,

and on this Seleucus II Callinicus began a third walled "city," which was finished by

Antiochus III. A fourth and last quarter was added by Antiochus IV Epiphanes (175-164 BC);

and thenceforth Antioch was known as Tetrapolis. From west to east the whole was about 6

km in diameter and little less from north to south, this area including many large gardens.

The new city was populated by a mix of local settlers, Athenians brought from the nearby city

of Antigonia, Macedonians, and Jews (who were given full status from the beginning). The

total free population of Antioch at its foundation has been estimated at between 17,000 and

25,000, not including slaves and native settlers.[1] During the late Hellenistic period and Early

Roman period, Antioch population reached its peak of over 500,000 inhabitants (estimates

vary from 400,000 to 600,000) and was the third largest city in the world after Rome and

Alexandria. By the 4th century, Antioch's declining population was about 200,000 according

to Chrysostom, a figure which again does not include slaves.

About 6 km west and beyond the suburb Heraclea lay the paradise of Daphne, a park of

woods and waters, in the midst of which rose a great temple to the Pythian Apollo, also

founded by Seleucus I and enriched with a cult-statue of the god, as Musagetes, by Bryaxis. A

companion sanctuary of Hecate was constructed underground by Diocletian. The beauty and

the lax morals of Daphne were celebrated all over the western world; and indeed Antioch as a

whole shared in both these titles to fame. Its amenities awoke both the enthusiasm and the

scorn of many writers of antiquity.

Antioch became the capital and court-city of the western Seleucid empire under Antiochus I,

its counterpart in the east being Seleucia on the Tigris; but its paramount importance dates

from the battle of Ancyra (240 BC), which shifted the Seleucid centre of gravity from Asia

Minor, and led indirectly to the rise of Pergamum.

Thenceforward the Seleucids resided at Antioch and treated it as their capital par excellence.

We know little of it in the Greek period, apart from Syria, all our information coming from

authors of the late Roman time. Among its great Greek buildings we hear only of the theatre,

of which substructures still remain on the flank of Silpius, and of the royal palace, probably

situated on the island. It enjoyed a great reputation for letters and the arts (Cicero pro Archia,

3); but the only names of distinction in these pursuits during the Seleucid period, that have

come down to us, are Apollophanes, the Stoic, and one Phoebus, a writer on dreams. The

mass of the population seems to have been only superficially Hellenic, and to have spoken

Aramaic in non-official life. The nicknames which they gave to their later kings were

Aramaic; and, except Apollo and Daphne, the great divinities of north Syria seem to have

remained essentially native, such as the "Persian Artemis" of Meroe and Atargatis of

Hierapolis Bambyce.

We may infer, from its epithet, "Golden," that the external appearance of Antioch was

magnificent; but the city needed constant restoration owing to the seismic disturbances to

which the district has always been peculiarly liable. The first great earthquake is said by the

native chronicler John Malalas, who tells us most that we know of the city, to have occurred

in 148 BC, and to have done immense damage.

The inhabitants were turbulent, fickle and notoriously dissolute. In the many dissensions of

the Seleucid house they took violent part, and frequently rose in rebellion, for example against

Alexander Balas in 147 BC, and Demetrius II in 129 BC. The latter, enlisting a body of Jews,

punished his capital with fire and sword. In the last struggles of the Seleucid house, Antioch

turned definitely against its feeble rulers, invited Tigranes of Armenia to occupy the city in 83

BC, tried to unseat Antiochus XIII in 65 BC, and petitioned Rome against his restoration in

the following year. Its wish prevailed, and it passed with Syria to the Roman Republic in 64

BC, but remained a civitas libera.

Roman period

The Romans both felt and expressed boundless contempt for the hybrid Antiochenes; but their

emperors favoured the city from the first, seeing in it a more suitable capital for the eastern

part of the empire than Alexandria could ever be, because of the isolated position of Egypt.

To a certain extent they tried to make it an eastern Rome. Caesar visited it in 47 BC, and

confirmed its freedom. A great temple to Jupiter Capitolinus rose on Silpius, probably at the

insistence of Octavian, whose cause the city had espoused. A forum of Roman type was laid

out. Tiberius built two long colonnades on the south towards Silpius. Agrippa and Tiberius

enlarged the theatre, and Trajan finished their work. Antoninus Pius paved the great east to

west artery with granite. A circus, other colonnades and great numbers of baths were built,

and new aqueducts to supply them bore the names of Caesars, the finest being the work of

Hadrian. The Roman client, King Herod, erected a long stoa on the east, and Agrippa

encouraged the growth of a new suburb south of this.

This argenteus was struck in Antioch mint, under Constantius Chlorus.

The chief events recorded under the empire are the earthquakes that shook Antioch. One, in

AD 37, caused the emperor Caligula to send two senators to report on the condition of the

city. Another followed in the next reign; and in 115, during Trajan's sojourn in the place with

his army of Parthia, the whole site was convulsed, the landscape altered, and the emperor

himself forced to take shelter in the circus for several days. He and his successor restored the

city; but in 526, after minor shocks, the calamity returned in a terrible form; the octagonal

cathedral which had been erected by the emperor Constantius II suffered and thousands of

lives were lost, largely those of Christians gathered to a great church assembly. Especially

terrific earthquakes on November 29, 528 and October 31, 588 are also recorded.

At Antioch Germanicus died in 19 AD, and his body was burnt in the forum. Titus set up the

Cherubim, captured from the Jewish temple, over one of the gates. Commodus had Olympic

games celebrated at Antioch, and in 256 the town was suddenly raided by the Persians, who

slew many in the theatre.

The Antioch Chalice, first half of 6th century, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Late Antiquity

The chief interest of Antioch under the empire lies in its relation to Christianity. Evangelized

perhaps by Peter, according to the tradition upon which the Antiochene patriarchate still rests

its claim for primacy (cf. Acts xi.), and certainly by Barnabas and Paul. Its converts were the

first to be called Christians (Acts 11:26). This is not to be confused with Antioch in Pisidia,

where the early missionaries later travelled to(Acts 13:14 - 13:50).

A bronze coin from Antioch depicting the emperor Julian. Note the pointed beard.

They multiplied exceedingly, and by the time of Theodosius were reckoned by Chrysostom at

about 100,000 people. Between 252 and 300, ten assemblies of the church were held at

Antioch and it became the seat of one of the four original patriarchates, along with Jerusalem,

Alexandria, and Rome (see Pentarchy). Today Antioch remains the seat of a patriarchate of

the Oriental Orthodox churches. One of the canonical Eastern Orthodox churches is still

called the Antiochian Orthodox Church, although it moved its headquarters from Antioch to

Damascus, Syria, several centuries ago (see list of Patriarchs of Antioch), and its prime bishop

retains the title "Patriarch of Antioch," somewhat analogous to the manner in which several

Popes, heads of the Roman Catholic Church remained "Bishop of Rome" even while residing

in Avignon, France in the 14th Century.

During the 4th century, Antioch was one of the three most important cities in the eastern

Roman empire (along with Alexandria and Constantinople), which led to it being recognized

as the seat of one of the five early Christian patriarchates (see Pentarchy).

When the emperor Julian visited in 362 on a detour to Persia, he had high hopes for Antioch,

regarding it as a rival to the imperial capital of Constantinople. Antioch had a mixed pagan

and Christian population, which Ammianus Marcellinus implies lived quite harmoniously

together. However Julian's visit began ominously as it coincided with a lament for Adonis, the

doomed lover of Aphrodite. Thus, Ammianus wrote, the emperor and his soldiers entered the

city not to the sound of cheers but to wailing and screaming.

Not long after, the Christian population railed at Julian for his favour to Jewish and pagan

rites, and, outraged by the closing of its great church of Constantine, burned down the temple

of Apollo in Daphne. Another version of the story had it that the chief priest of the temple

accidentally set the temple alight because he had fallen asleep after lighting a candle. In any

case Julian had the man tortured for negligence (for either allowing the Christians to burn the

temple or for burning it himself), confiscated Christian property and berated the pagan

Antiochenes for their impiety.

Julian found much else about which to criticize the Antiochenes. Julian had wanted the

empire's cities to be more self-managing, as they had been some 200 years before. However

Antioch's city councilmen showed themselves unwilling to shore up Antioch's food shortage

with their own resources, so dependent were they on the emperor. Ammianus wrote that the

councilmen shirked their duties by bribing unwitting men in the marketplace to do the job for

them.

The city's impiety was also clear when Julian went to attend the city's annual feast of Apollo.

To his surprise and dismay the only Antiochene present was an old priest clutching a chicken.

The Antiochenes in turn hated Julian for worsening the food shortage with the burden of his

billeted troops, wrote Ammianus. The soldiers were often to be found gorged on sacrificial

meat, making a drunken nuisance of themselves on the streets while Antioch's hungry citizens

looked on in disgust. The Christian Antiochenes and Julian's pagan Gallic soldiers also never

quite saw eye to eye.

Even Julian's piety was distasteful to the Antiochenes. Julian's brand of paganism was very

much unique to himself, with little support outside the most educated Neoplatonist circles.

The irony of Julian's enthusiasm for large scale animal sacrifice could not have escaped the

hungry Antiochenes. Julian gained no admiration for his personal involvement in the

sacrifices, only the nickname axeman, wrote Ammianus.

The emperor's high-handed, severe methods and his rigid administration prompted

Antiochene lampoons about, among other things, Julian's unfashionably pointed beard. In

reply Julian published the curious satiric apologia, still extant, which he called Misopogon

(beard hater). Ammianus Marcellinus writes that by the time Julian left the city for his

Persian campaign, the Antiochenes cried that even the Christians had never been this cruel. In

return, Julian appointed over them a magistrate known for his cruelty.

Julian's successor, Valens, who endowed Antioch with a new forum, including a statue of

Valentinian on a central column, reopened the great church of Constantine, which stood till

the Persian sack in 538 by Chosroes.

In 387, there was a great sedition caused by a new tax levied by order of Theodosius I, and the

city was punished by the loss of its metropolitan status.

Justinian I, who renamed it Theopolis ("City of God"), restored many of its public buildings

after the great earthquake of 526, whose destructive work was completed by the Persian king,

Khosrau I, twelve years later. Antioch lost as many as 300.000 people. Justinian I made an

effort to revive it, and Procopius describes his repairing of the walls; but its glory was past.

Antioch gave its name to a certain school of Christian thought, distinguished by literal

interpretation of the Scriptures and insistence on the human limitations of Jesus. Diodorus of

Tarsus and Theodore of Mopsuestia were the leaders of this school. The principal local saint

was Simeon Stylites, who lived an extremely ascetic life atop a pillar for 40 years some 65 km

east of Antioch. His body was brought to the city and buried in a building erected under the

emperor Leo.

Arab period

The ramparts of Antioch climbing Mons Silpius during the Crusades (lower left on the map,

above left)

In 637, during the reign of the Byzantine emperor Heraclius, Antioch was conquered by the

Muslims forces of the Rashidun Caliphate during the Battle of Iron Bridge, and became

known in Arabic as ةنطاكينةAntākiyyah. Later since the Umayyad dynasty was unable to

penetrate the Anatolian plateau, Antioch found itself on the frontline of the conflicts between

two hostile empires during the next 350 years, so that the city went into a precipitous decline.

In 969, the city was recovered for the Byzantine Emperor Nicephorus II Phocas by Michael

Burza and Peter the Eunuch. In 1078, the Seljuk Turks captured Antioch, but held it only

fourteen years before the Crusaders arrived.

Muslims believe that it will be found by Mahdi near the end of times in the city of Antakya or

Antioch.

Crusader era

Capture of Antioch by Bohemond of Tarente in June 1098.

The Siege of Antioch by the Crusaders took place during the First Crusade, during which it

endured frightful suffering. Although it contained a large Christian population, it was

ultimately betrayed by Islamic allies of Bohemund, prince of Taranto, who became its lord. It

remained the capital of the Latin Principality of Antioch for nearly two centuries. It fell at last

to the Egyptian Mamluk Sultan Baibars, in 1268, after another siege. Baibars proceeded to

massacre the Christian population and destroy many of the churches. In addition to the

ravages of war, the city's port had become inaccessible to large ships due to the accumulation

of sand in the Orontes river bed. As a result, Antioch never recovered as a major city, with

much of its former role falling to the port city of Alexandretta (Iskenderun).