Semitische talen

Proto-Semitic Language and Culture

John Huehnergard

The Appendix of Semitic Roots (Appendix II) that follows this essay is designed to allow

the reader to trace English words derived from Semitic languages back to their

fundamental components in Proto-Semitic, the parent language of all ancient and modern

Semitic languages. This introduction to the Appendix provides some basic information

about the structure and grammar of Semitic languages as an aid to understanding the

etymologies of these words. In the text below, terms in boldface are Semitic roots that

appear as entries in Appendix II. Words in small capitals are Modern English derivatives

of Semitic roots. An asterisk (*) is used to signal a word or form that is not preserved in

any written document but that can be reconstructed on the basis of other evidence.

1

The Semitic Language Family

The Semitic language family has the longest recorded history of any linguistic group. The

Akkadian language is first attested in cuneiform writing on clay tablets from ancient

Mesopotamia (modern Iraq) from the mid-third millennium B.C., and Semitic languages

continue to be spoken in the Middle East and in northeastern Africa today.

Modern Semitic languages include Arabic, spoken in a wide variety of dialects by

nearly 200 million people as the official language of over a dozen nations, and in many

other countries as well; Amharic, the official language of Ethiopia; Hebrew, one of the

official languages of Israel; Tigrinya, the official language of Eritrea; Aramaic, the

language of the Jewish Talmud and of Jesus, first attested in inscriptions written three

thousand years ago and still spoken by several hundred thousand people in the Middle

East and elsewhere.

Ancient Semitic languages include Akkadian, the language of the ancient Babylonians

2

3

4

and Assyrians; Phoenician and its descendant Punic, the language of Carthage, the

ancient enemy of Rome; the classical form of Hebrew as recorded in the Hebrew

Scriptures and later Jewish writings; the languages of the neighbors of the ancient

Israelites, such as the Ammonites and Moabites; many early dialects of Aramaic; the

classical Arabic of the Koran and other Muslim writings; Old Ethiopic texts of the

Ethiopian Christian church; and South Arabian languages attested in inscriptions found in

modern Yemen, such as Sabaean, the language of the ancient Sheba of the Bible.

In the same way that English is a member of the sub-family of Germanic languages

within Indo-European, the Semitic languages constitute a sub-family of a larger linguistic

stock, formerly called Hamito-Semitic but now more often called Afro-Asiatic. Other

branches of Afro-Asiatic include ancient Egyptian (and its descendant, Coptic), the

Berber languages of north Africa, the Cushitic languages of northern East Africa (such as

Somali and Oromo), and the Chadic languages of western Africa (such as Hausa in

Nigeria).

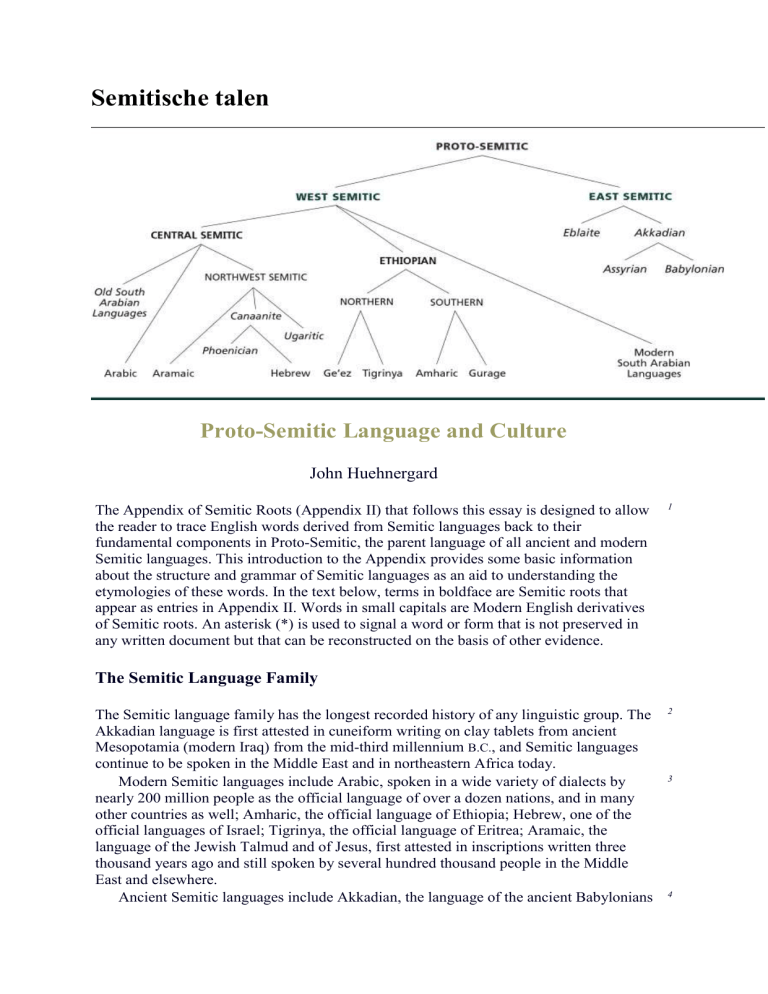

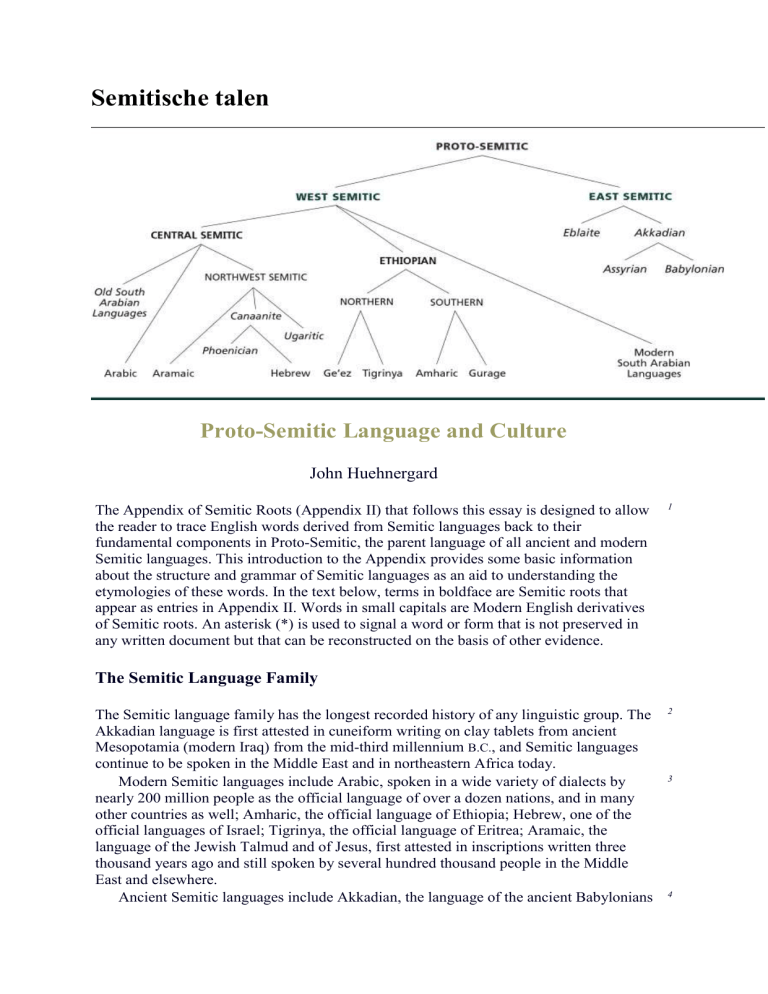

Various significant linguistic features allow us to classify the many Semitic languages

in a way that shows the historical branching off of sub-groups. The ancient ancestor of all

the Semitic languages, like Proto-Indo-European a prehistoric, unwritten language, is

called Proto-Semitic or Common Semitic. The earliest branching, which includes most of

the known Semitic languages, is called West Semitic; the part that remained after this

branching, East Semitic, essentially includes only Akkadian. West Semitic comprises

three branches: the modern South Arabian languages; the ancient and modern languages

of Ethiopia; and Central Semitic. Central Semitic is further subdivided into the South

Arabian inscriptional languages; classical, medieval, and modern forms of Arabic; and

the Northwest Semitic languages, which include Hebrew and Aramaic. See the “Chart of

the Semitic Family Tree”.

5

6

Semitic Words, Roots, and Patterns

A distinctive characteristic of the Semitic languages is the formation of words by the

combination of a “root” of consonants in a fixed order, usually three, and a “pattern” of

vowels and, sometimes, affixes before and after the root. The root indicates a semantic

field, while the pattern both narrows meaning and provides grammatical information. For

example, if we represent the three root consonants abstractly as X’s, in Arabic the pattern

XaXaXa produces a verb form, called the perfect, in the third person masculine singular.

7

Applying this pattern to the root -r-m, indicating the notion of “banning, prohibiting”

(see rm), Arabic forms the perfect third person masculine singular arama, “he

prohibited.” Another pattern, XaX X, yields a derived noun, in this case the word ar m,

“forbidden place,” the source of English HAREM, while the pattern iXX X yields a verbal

noun, i r m, “prohibition,” the source of English IHRAM. The pattern muXaXXaX (with

doubling of the middle root consonant) yields a passive participle, mu arram, English

MUHARRAM. This last pattern is also found, for example, in the personal name

Arabic mu ammad, from the root -m-d, “to praise” (see md).

In most Semitic languages, sound changes have obscured some of the underlying

patterns. For example, Arabic k f, the origin of English KIF, is a dialectal variant of

classical Arabic kayf, a form of the Arabic root k-y-f with the pattern XaXX. Hebrew tôrâ

(TORAH) is historically an example of the pattern taXXaXat; the earlier form was

*tawrawat-, from the root that was originally w-r-w in Semitic (“to guide”; see wrw), and

MUHAMMAD,

8

regular sound shifts in the history of the language changed *tawrawat- to tôrâ.

The prominence of the root-and-pattern system makes it relatively easy to determine

both constituents of most Semitic words. This in turn allows the comparison of individual

roots across languages. Thus, for example, Arabic sal m, “peace, well-being” (English

SALAAM),

from the Arabic root s-l-m, is clearly cognate with Hebrew

9

lôm, which has

the same meaning (English SHALOM), from the Hebrew root -l-m; both reflect the same

Proto-Semitic root, lm. The patterns, too, in this case are cognate; the Proto-Semitic

pattern *XaX X, still seen in the Arabic form, regularly develops into X XôX in Hebrew.

For most words associated with verbal roots, however, the distribution and semantic

function of the various possible patterns are specific to individual languages. The original

patterns of specific words very often shifted to other patterns during the separate histories

of the various languages after they branched off from their ancestral subgroups. For

example, Arabic and Hebrew share a common root, -k-m, “to be wise”; but the attested

form of the adjective meaning “wise” in Arabic has the pattern XaX X, ak m (English

HAKIM1; see km), while in Hebrew it has the pattern X X X (a Hebrew development of

Proto-Semitic *XaXaX), k m.

Because of these pattern shifts, it is usually not possible to reconstruct individual

words back to Proto-Semitic, only individual roots. The Appendix that follows is

therefore a list of Semitic roots rather than of individual words. An important group of

exceptions to this generalization includes words that denote physical objects, such as

“hand,” “rock,” and “house.” While such words may be associated with derived roots of

verbs (as in English to house), the substantives are clearly primary, and it is often possible

to reconstruct them back to Proto-Semitic, or at least to intermediate stages, such as

Proto-Central Semitic or Proto-West Semitic. Such reconstructed forms are given in the

Appendix where appropriate; to facilitate the arrangement of the Appendix, they have

been listed under the consonantal root that can be extracted from the reconstruction,

rather than as entries unto themselves. Thus Proto-Semitic *bayt-, “house,” is listed under

byt. Some of these words have only two consonants, or rarely only one, rather than the

usual three consonants that make up verbal roots; thus, Proto-Semitic * il-, “god,” is

listed under l, Proto-Semitic *yad-, “hand,” under yd, and Proto-Semitic *pi- or *pa-,

“mouth,” under p.

10

Proto-Semitic Sounds and Their Development in the Languages

The Proto-Semitic sound system had three short vowels, a, i, u, and three corresponding

long vowels, , , ; these vowels are preserved essentially unchanged in classical Arabic

but have undergone numerous developments in most of the other Semitic languages, both

ancient and modern.

Proto-Semitic had 29 consonants. These are shown as the first row of sounds in the

Table of Proto-Semitic Sound Correspondences. There were five triads of homorganic

consonants (pronounced in the same area of the mouth); each triad consisted of a voiced,

voiceless, and emphatic consonant. The emphatic consonants are characteristic of

Semitic; in Proto-Semitic they were probably glottalized, that is, produced with a

simultaneous closing of the glottis in the throat; this is how they are still pronounced in

the Ethiopian Semitic languages. (In Arabic, however, emphatics is the name given to

pharyngealized consonants, that is, those pronounced with a constriction of the pharynx

and a raising of the back of the tongue.) The five triads were: (1) the interdental fricatives

11

12

, , and (with and pronounced as th in English then and thin, respectively); (2) the

dental stops t, d, and (with t and d as in English, and , a glottalized t, represented

phonetically as [t’]); (3) the alveolar affricates s, z, , which were pronounced (ts), (dz),

and glottalized (ts’), respectively; (4) the laterals l, , and (with l pronounced as in

English light and as a voiceless l like the Welsh sound written ll); and (5) the velar stops

g, k, q (with g as in English go, k as in kiss, and the q as an emphatic k).

In addition to these triads, there were a number of pairs of consonants that lacked an

emphatic counterpart: two labial stops, voiced b and unvoiced p (the latter becoming f in

Arabic, Ethiopian Semitic languages, and sometimes in Hebrew and Aramaic); two velar

13

fricatives, voiced , pronounced like a French r, and voiceless , pronounced like the ch

in Scottish loch or German Bach; two distinctively Semitic pharyngeals, voiced “ayin,”

indicated by the raised symbol , and unvoiced , both somewhat like h but formed by

constricting the pharynx; and two glottal consonants, the glottal stop (like the catch in

the voice in the middle of English uh-oh), and glottal fricative, h. Finally, there was a

sibilant, transcribed and pronounced sh in Hebrew but as a simple s in Arabic and in

Proto-Semitic; and five additional resonants besides l: m, n, r, w, and y.

All of the 29 Proto-Semitic consonants are preserved as distinct sounds in the Old

South Arabian languages (such as Sabaean), but in the other Semitic languages various

mergers of the original consonants have occurred. Thus Akkadian, the earliest-attested

Semitic language, has only 18 consonants. The outcomes of the Proto-Semitic consonants

in Akkadian, Ethiopic, Arabic, Hebrew, and Aramaic are illustrated in the table "ProtoSemitic Sound Correspondences".

14

Grammatical Forms and Syntax

Semitic nouns exhibit two grammatical genders, masculine and feminine. Masculine

nouns have no special marker, whereas the majority of feminine nouns have an ending

after the masculine stem, usually either -at or -t, as illustrated by the pairs *ba l-, “owner,

lord” (as in BAAL and HANNIBAL) versus *ba lat-, “owner, lady” (see b l), and *bn-,

“son” (as in BENJAMIN) versus *bint- (from *bnt-), “daughter” (as in BAT MITZVAH; see

bn). A few feminine nouns have no such marker, however, such as * imm-, “mother,” and

* ayn-, “eye” (see yn).

The declension of the noun in early Semitic is relatively uncomplicated. There were

three cases, a nominative (for subjects of sentences and for predicates of verbless

sentences), genitive (for possession and after all prepositions), and accusative (for the

direct object of the verb and for sundry adverbial forms). A characteristic feature of

Semitic nouns is the so-called bound form or construct form, an endingless form taken by

a noun when it is followed directly by a possessor noun or by a possessive pronoun

suffix. For example, the Arabic word anabun means “tail,” but the ending -n is dropped

in the possessive phrases anabu asadin, “tail of a lion,” and anabu-hu, “his tail.”

Several English words derived from Semitic phrases, such as the star names DENEBOLA

and FOMALHAUT, come from a word in the bound form.

Both Arabic and Hebrew have a definite article (but no indefinite article); in both, the

article is prefixed to its noun. In Hebrew the form of the article is ha-, usually with

doubling of the first consonant of the noun, as in ha - nâ, “the year” (ROSH HASHANAH)

15

16

17

from nâ, “year” (see n). In Arabic the form of the article is al-; the a of al- is omitted

when a preceding word ends in a vowel, and the l assimilates to many of the consonants it

precedes. The article also causes the final n of forms such as anabun, “tail,” and

asadun, “lion,” to be omitted: a - anabu, “the tail,” al- asadu, “the lion.” When a

construct phrase, such as anabu asadin, “the lion’s tail,” is made definite, the article

appears only on the second member of the phrase: anabu l- asadi, “the lion’s tail.” Many

Arabic nouns were borrowed together with the article into European languages, especially

into Spanish; this is the source of the al- in a number of English words of Arabic origin,

such as ALCOHOL, ALEMBIC, and ALGEBRA, as well as other words where the article has

been altered, such as ARTICHOKE and AUBERGINE.

Most Semitic languages exhibit two types of finite verbs. One type, which is usually

called the perfect and is used for completed action, has a set of endings to indicate the

person, gender, and number of the subject, as in Arabic daras-a, “he studied,“ daras-at,

18

“she studied,” daras-tu, “I studied,“ and Hebrew d ra , “he studied” (with no ending), d

r â, “she studied,” d ra -tî, “I studied” (see dr ). In the other type, the subject is

indicated by prefixes (and, for some forms, endings as well), and the verbal root has a

different pattern of vowels from the perfect, as in Arabic ya-drus-u, “he studies,” ta-drusu, “she studies,” a-drus-u, “I study,” and Hebrew yi-dr , “he studies,” ti-dr , “she

studies,” e-dr , “I study.” The third person masculine singular form of the perfect is

customarily used as the citation form of a verb; traditionally, however, its English

translation is given as an infinitive, and this practice is followed in Appendix I. Thus

under hgr, the Arabic verb hajara is glossed as “to depart,” although the actual meaning

of that form is “he departed.”

In addition to the two forms just noted, Semitic verbs also have a rich variety of

derived stems that variously modify the basic meaning of the verbal root. Thus the Arabic

root k-t-b, expressing the notion of “writing,” forms a verb whose basic (perfect) form is

kataba, “to write”; with a long vowel in the first syllable, k taba, it means “to correspond

(with someone)”; with in- prefixed, it is a passive, inkataba, “it was written”; and with aprefixed, it is causative, aktaba, “to cause to write, to dictate.” For simplicity’s sake,

such derived forms of the verbal root are labeled in the Appendix as “derived stems.”

19

Lexicon and Culture

As in the case of Indo-European, the reconstruction of Proto-Semitic words and roots

offers us a glimpse of the world and the culture of its speakers.

Several kinship terms can be reconstructed, a number of which suggest that ProtoSemitic society was patriarchal. Although the words for “father,” * ab- ( b), and

“mother,” * imm- ( mm), are distinct, the word for “daughter,” *bint-, is the grammatical

feminine of “son,” *bn- (bn), and “sister,” * a t-, is likewise a feminine of the word for

“brother,” * a - ( ). Separate words for “husband’s father,” * am-, and “father’s

kinsman, clan,” * amm- ( mm), are found, but the feminine equivalents are simply

derived from these. Interestingly, the words for “son-in-law, bridegroom,” * atan-, and

“daughter-in-law,” *kallat-, are unrelated to each other. A word for “widow,” * almanat-,

can be reconstructed, but not one for “widower.”

Other Proto-Semitic words provide more glimpses into the social structure. That it

20

21

22

was stratified is shown by the existence of words for “king” or “prince” (two are found,*

arr- and *malk-, the latter of which is associated with the verbal root mlk, “to rule”),

“lord, owner, master,” *ba l- (and the feminine *ba lat- “lady”; see b l), and “female

slave,” * amat-. (No masculine counterpart is reconstructible; slaves were perhaps

acquired as prisoners of war, the males being killed.) Communities had judges who

adjudicated (dyn) over local disputes.

There is no Proto-Semitic word for “religion,” but several religious terms can be

23

reconstructed, such as * b , “to sacrifice”; m , “to anoint”; rm, “to ban, prohibit”; qd

, “to be holy, sacred” (as well as ll, “to be clean, pure, holy”); and * alm-, “(cult)

statue.” There is a Proto-Semtic word for “god,” * il- ( l); the names of the earliest

Semitic gods for the most part denoted natural elements or forces, such as the sun, the

moon, the morning and evening stars, thunder, and the like (see under tr, m , wr ).

There are many Proto-Semitic terms referring to agriculture, which was a significant

24

source of livelihood. Words for basic farming activities are well represented: fields (*

aql-) were plowed (* r ), sown (* r ), and reaped ( d); grain was trampled or threshed

(*dy ) and winnowed ( rw) on a threshing floor (*gurn-), and ground ( n) into flour

(*qam -). Words for several specific grains can be reconstructed, including wheat (* in ), emmer (*kun -), barley (* i r-; West Semitic only, related to Proto-Semitic * a r“hair”), and millet (*du n-). The words for many other agricultural products may provide

clues as to the original homeland of the Semites, though this is a matter of conjecture and

dispute: they were acquainted with figs (*ti n-), garlic (* m-), onion (*ba al-, replaced

in Akkadian by a Sumerian word), palm trees (*tamr- or *tamar-; see tmr), date honey

(*dib -), pistachios (*bu n-), almonds (* aqid-), cumin (*kamm n-; see kmn), and groats

or malt (*baql-), as well as oil or fat (* amn-; see mn). The early Semites cultivated

grapes (* inab-) growing on vines (*gapn-) in vineyards (*karm- or *karn-), from which

they produced wine (*wayn-, akin to Indo-European words for wine and probably a

loanword in Proto-Semitic as well). Another alcoholic beverage, * ikar- ( kr), was also

known; it was stronger than *wayn-, perhaps fermented or distilled.

Also of Proto-Semitic antiquity are the names of a number of domesticated animals

and several words denoting products and activities associated with them. We can

reconstruct separate words for “sheep” (* immar-), “ewe” (*la ir-, see l r), and “shegoat” (* inz-), as well as separate words for “flock of sheep” (* aw-) and “mixed flock of

sheep and goats” (* a n-). Sheep were shorn (*gzz) and the flocks “tended” or “herded”

(r y, with the participle *r iy-, “herder”) and given to drink ( qy, a root also meaning “to

irrigate”). A general word for “bovine” was *li - (feminine *li at-), in addition to which

come * alp-, “ox” ( lp) and * awr- “bull” (the latter perhaps a borrowing of IndoEuropean *tauro-, just as Proto-Semitic *qarn-, “horn” may be of Indo-European origin;

see tauro- and ker-1 in Appendix I). The pig (* zr or * nzr) and the dog (*kalb-) were

domesticated, as were donkeys, for which separate words for the male (* im r-; see mr)

and the female (* at n-) can be reconstructed. Dairy production is shown by *la ad-,

“cream,” and * im at-, “curds, butter.”

25

The level of technology that the reconstructed Proto-Semitic vocabulary points to is

that of the late Neolithic or early Chalcolithic. The early Semites, or at least some of

them, lived in houses (*bayt-; see byt) with doors (*dalt-; see dl), containing at least

26

chairs (*kussi -) and beds (* ar -) for furniture. They dug (*kry) wells (*bi r-), lit (* rp)

fires (* i -), and roasted (qly) food (*la m-; see l m). A number of words dealing with

mining are found: the Semites had learned to smelt ( rp) ores with coal (*pa am-) to

obtain metals (only “silver,” *kasp-, is Proto-Semitic; words for “gold,” “copper,”

“bronze,” and “iron” are not reconstructible). Bitumen (*kupr-) was used for

waterproofing. They also used antimony (*ku l-; see k l) and naphtha (*nap -; see np ),

and manufactured rope (* abl-). The early Semites made use of bows (*qa t-) and arrows

(* a w-). In transactions, they weighed ( ql), measured (*mdd), and otherwise counted

(mnw) things, and sometimes, at least, found time to play music (zmr).

Of particular interest in the reconstruction of the non-material culture of the ProtoSemites is the structure of personal names. Personal names in most Semitic languages

have traditionally consisted of meaningful phrases or sentences that express a religious

sentiment, usually with reference to a deity. Some names are phrases of the type “X of

god,” as in the Hebrew name y dîdy h (Jedidiah), “beloved of Yah” (Yah being a

shortened form of the name of the god of Israel, Yahweh; see dwd, hwy) and the Arabic

name abdull h (Abdullah), “servant of Allah.” In other Arabic names, an epithet of Allah

appears instead, as in abduljabb r (Abdul-Jabbar), “servant of the Almighty,” from

jabb r, “powerful, almighty.” Many Semitic names constitute a complete sentence. Some

of these contain a verb form, as in Hebrew z kary h (Zechariah), “Yahweh has

27

remembered” (that is, has remembered the parents; see zkr) and yô n n (John),

“Yahweh has been gracious” (see nn), and in Akkadian Sîn-a -er ba (Sennacherib),

“(the god) Sin has replaced the (lost) brothers for me” (see r b) and A ur-a a-iddin

(Esarhaddon), “(the god) Ashur has given a brother” (see ntn). Other sentence-names are

simply two words juxtaposed to form a nominal sentence with understood verb “to be,” as

in Hebrew lîy h (Elijah), “Yahweh (is) my god” (see l, hwy) and abr h m (Abraham),

“the (divine) father (is) exalted” (see b, rhm); Akkadian tukult -apil-e arra

(Tiglathpileser), “my trust (is) the heir of Esharra” (see wkl); and Amorite ammu-r pi

(Hammurabi), “the (divine) kinsman is a healer” (see rp ).

28

One-word names also occur, as in Arabic a mad (Ahmed), mu ammad

(Muhammad), and ma m d (Mahmoud), which reflect different forms of a root meaning

“to praise” (see md), asan (Hasan) and usayn (Hussein), both meaning “handsome,

excellent,” and asad (Asad), “lion” (see d); and in Hebrew d w d (David), “beloved”

(see dwd) and yônâ (Jonah), “dove” (see ywn). Most women’s names are of this type; for

example, Arabic f ima (Fatima), “she who weans,”

(Sarah), “princess” (see rr), and r

i a (Aisha), “living,” Hebrew

râ

l (Rachel), “ewe” (see l r).

Semitic Words in English

Since English is an Indo-European language and therefore not genetically related to the

Semitic family, all words of Semitic origin in English are loanwords. Roughly 700 of the

29

words listed in this Dictionary have come into English by way of a Semitic language. For

over 90 percent of these, the Semitic language is Arabic (over 400) or Hebrew (over 250).

Not all such words originated in a Semitic language, however. Some of them are

loanwords into Semitic from another source. In the case of several words that have come

through Arabic, for example, the Arabic word is originally Persian, as in the case of

JULEP, borrowed into Middle English from Old French, into Old French from Late Latin,

and into Late Latin from Arabic jul b; but Arabic jul b itself is from Persian gul b,

“rosewater.” Here, the Indo-European English, French, and Latin have borrowed from the

Semitic Arabic, which in turn has borrowed from another Indo-European language,

Persian. Such words will not be found in this Appendix, but if they are derived from an

Indo-European root, may be found in the Appendix of Indo-European roots preceding. A

number of scientific and technical terms borrowed from Arabic were first borrowed by

Arabic from Greek, such as ALEMBIC, from Old French, from Medieval Latin, from

Arabic al- anb q, “still” (with the Arabic article al-), from Greek ambix, “cup.” Still

others have a more remote or ancient source; the common English word ADOBE, which

came into English from Spanish, came into Spanish from Arabic a - ba, “the brick”

(with the article al-, here assimilated to the - of the noun), but the Arabic word is of

ancient Egyptian origin, Coptic t be and classical Egyptian bt, “brick.” The word

TUNIC, from Latin, entered Latin from a Semitic language akin to Hebrew (perhaps

Punic-Phoenician), which in turn had borrowed it from another Semitic language,

Akkadian, which in turn had borrowed it from Sumerian (gada, linen), a non-Semitic

language of ancient Mesopotamia.

Most of the words that have come into English from a Semitic language, however, are

also Semitic in origin. The following Appendix of Semitic roots lists over 550 such

words. Again, the most common language of origin is Arabic, followed by Hebrew. There

are also a few dozen words that originate in other Semitic languages, especially Aramaic

and Akkadian. In most cases, an Aramaic or Akkadian word has first entered Arabic or

Hebrew, whence it then found its way to English; for example, SOUK, a Middle Eastern

market, is borrowed from Arabic s q, which was borrowed from Aramaic q, which in

turn was borrowed from Akkadian s qu, which meant “street,” from a Semitic root

meaning “to be narrow or tight” (see yq).

Many of the Semitic words that have come into English fall into a few important

semantic categories. The names of the letters of the Hebrew alphabet are of course

Semitic in origin, though for the most part not Hebrew but Phoenician, a close relative of

Hebrew; also of Phoenician origin are the names of Greek letters, such as ALPHA and

BETA, and the word ALPHABET that is derived from the latter (see lp, byt). Many of the

Semitic words are star names, such as ALTAIR, BETELGEUSE, and VEGA, which derive

originally from Arabic words or phrases (see yr, gwz and yd, wq ). Other large semantic

groups are formed by words having to do with religious customs and practices, such as

ABBOT, AMEN, ARMAGEDDON, AYATOLLAH, BAR/BAT MITZVAH, HALLELUJAH, JIHAD,

KOSHER, MOSQUE, MUEZZIN, RABBI, SATAN, TORAH; business terms, such as ABACUS,

ARSENAL, AVERAGE, MINA, SILVER, TARIFF; words for trade goods and similar items,

including plant names such as BALSAM, COTTON, CUMIN, GALBANUM, HASHISH,

HUMMUS, HYSSOP, MYRRH, SAFFLOWER, SESAME, but also many others, such as AMBER,

CANE, CIDER, COFFEE, GYPSUM, HOOKAH, JACKET, JAR, MAT, MATTRESS, MOHAIR,

NAPHTHA, RACKET, REAM, SACK, SEMOLINA, SEQUIN; names of animals, including

ALBACORE, ALBATROSS, BEHEMOTH, CAMEL, GIRAFFE; and, in addition to the star

names mentioned earlier, other scientific terms, such as ALCOHOL, ALGEBRA, ALIDADE,

30

31

ALKALI, CIPHER, NADIR, SODA, ZENITH,

and ZERO. The names of the months of the

Jewish calendar and the months of the Muslim calendar have naturally entered English

from Hebrew and Arabic, respectively, but it is interesting to note that most of the Jewish

month names were originally at home in ancient Mesopotamia and were borrowed into

Hebrew from Akkadian. The Semitic languages are also the origin of many proper names

in English, such as the names of many of the books of the Bible, as well as given names

such as ABRAHAM, ADAM, ANN, JACOB, JACK, and RACHEL. The name MICHAEL, which

comes from Hebrew mîk l, meaning “who is like God?” (see the Appendix under my1,

l), may be humanity’s oldest continuously used name, for it is found not only in the

Hebrew of the Bible but also in Eblaite, a Semitic language closely related to Akkadian,

from about 2300 B.C.

In spite of the fact that the Semitic languages have been known and studied by

scholars for many hundreds of years, the comparative reconstruction of Proto-Semitic is

in many ways still in its infancy. The historical linguistics of the Semitic languages has

not traditionally focused as much on reconstruction as Indo-European historical

linguistics has, and the philological study of the individual languages has remained rather

insular. This Appendix of Semitic Roots, while by no means the first comparative Semitic

glossary, is the first such work to attempt systematically to give reconstructed forms and

meanings for such a wide variety of roots and words. Time and further discoveries will no

doubt result in the modification of some of the material here; new information on the

ancient Semitic languages is constantly coming to light through archaeological finds, and

ongoing linguistic study of the ancient and modern languages is sure to advance our

knowledge as well.

Semitische talen

De Semitische talen vormen een noordoostelijke subfamilie van de Afro-Aziatische talen. De

meest voorkomende Semitische talen zijn Arabisch, Amhaars, Hebreeuws en Tigrinya. Ook

het Maltees is een Semitische taal.

De naam Semitisch is afgeleid van Sem, één van de zonen van Noach. De term "Semitische

taal" komt als zodanig niet in de Thora voor, maar wordt beschouwd als een academische

term.

In Genesis 10 wordt vermeld dat de zonen van Noach Sem, Cham en Jafeth heten. Onder de

zonen van Sem bevinden zich Asshur en Aram, waar de namen voor het Assyrisch en

Aramees van afgeleid zijn.

Opmerkelijk is daarom dat de Semitische taal Hebreeuws in de Bijbel zelf 'taal van Kanaän'

(sefat Kena'an) wordt genoemd. Hebreeuws is ook daadwerkelijk, net als het Fenicisch, een

taal van de streek Kanaän, en geen geïmporteerd Aramees. Kanaän stamt volgens Genesis af

van Cham, net als Kush en Mitsraim (Egypte). Tot voor kort noemde men de Afrikaanse tak

van de Afro-Aziatische talen dan ook de Hamitische talen. Thans ziet men in dat de vier

afdelingen hiervan onderling zo verschillend zijn dat ze elk als een aparte tak moeten worden

beschouwd, op gelijke hoogte als de Semitische tak.

Inhoud

1 Overzicht van talen binnen de taalfamilie

o 1.1 Oost-Semitische talen

o 1.2 Centraal-Semitische talen

1.2.1 Noordwest-Semitische talen

1.2.2 Arabische talen

o 1.3 Zuid-Semitische talen

1.3.1 Westelijk

1.3.2 Oostelijk

2 Gedeelde kenmerken

3 Verschillende kenmerken

Overzicht van talen binnen de taalfamilie

Oost-Semitische talen

Akkadisch -- uitgestorven

Akkadisch

De taal Akkadisch is geattesteerd van de Faraperiode (ca. 2800 v.Chr.) tot de 1e eeuw na

Chr., al werd het als gesproken taal in de laatste eeuwen voor Christus geleidelijk vervangen

door het Aramees en bleef het hoofdzakelijk als geleerde taal verder leven (vgl. het Latijn in

de Middeleeuwen).

Mesopotamië was het thuisland van deze taal, maar op verschillende tijdstippen werd het ook

ver buiten dit gebied gebruikt, gaande van Perzië in het oosten tot Syrië-Palestina en Egypte,

waar het als diplomatieke taal diende, in het westen.

Gedurende die lange periode en verspreid over zo'n immens gebied onderging het uiteraard

wijzigingen. Men onderscheidt dan ook binnen de term Akkadisch verschillende dialecten.

Een overzicht :

Babylonisch

Schrijftaal

Assyrisch

Oud-Akkadisch

(2500-1950)

Oud-Babylonisch

(1950-1530)

Oud-Assyrisch

(1950-1750)

Midden-Babylonisch

(1530-1000)

Midden-Assyrisch

(1500-1000)

Neo-Babylonisch

(1000-625)

Standaard Babylonisch

(1500-500)

Neo-Assyrisch

(1000-600)

Laat-Babylonisch

(625-75 A.D.)

We zien dat er van het begin van het 2e millennium tot het einde van het Assyrische rijk een

indeling bestaat in twee dialecten, Babylonisch en Assyrisch.

Na de Oud-Babylonische periode loopt parallel naast de gesproken taal een artificieel

geschreven vorm van de taal (Standaard Babylonisch), die sterk aansluit bij het OudBabylonische dialect.

Naast deze centrale dialecten zijn er meerdere perifere dialecten geattesteerd. Dit zijn alle

geschreven varianten van het Akkadisch, beïnvloed door verschillende lokale dialecten (Susa,

Boghazköy, Alalah, Nuzi, Ugarit, Amarna).

De teksten, bewaard in het Akkadisch, zijn van velerlei aard: rituelen, gebeden, hymnen,

voorspellingen, literatuur, brieven, contracten, zakelijke bestanden, verdragen, ...

http://xoomer.alice.it/bxpoma/akkadeng/akkadengindex.htm

I.1

e-nu-ma e-lish la na-bu-ú shá-ma-mu

enüma elish lä nabû shamämü

'When above heaven was not (yet) named'

I.2

shap-lish am-ma-tum shu-ma la zak-rat

shaplish ammatum shuma lä zakrat

'(and) below the earth was not pronounced by name'

I.3

zu.ab-ma resh-tu-ú za-ru-shu-un

abzu-ma rështû zärûshun

'and Apsu, the first one/the ancient Apsu, their begetter

.4

mu-um-mu ti-amat mu-al-li-da-at gim-ri-shú-un

Mummu Tiämat mu(w)allidat gimrishun

'(And) maker Tiamat, who bore them all'

.5

a.mesh-shú-nu

ish-te-nish i-hi-qu-ú-ma

mêshunu ishtënish ihïqüma

'(and when they) had mixed their waters together'

I.6

gi-pa-ra la ki-isc-scu-ru scu-sca-a la she-'u-ú

gipa(r)ra lä kiscscurü scuscä lä she'û

'(but when) pastures were not (yet) formed , nor reed-beds were made'

I.7

e-nu-ma dingir.dingir la shu-pu-u ma-na-ma

enüma ilü lä shüpû manäma

'When none of the gods were (yet) manifest

Eblaïtisch -- uitgestorven, is ofwel Oost-Semitisch ofwel Noordwest-Semitisch.

Eblaite language

Eblaite is an extinct, perhaps East Semitic language, which was spoken in the 3rd millennium

BCE in the ancient city of Ebla, in modern Syria. It is considered to be the oldest written

Semitic language.

The language, closely related to Akkadian, is known from about 17,000 tablets written with

cuneiform script which were found between 1974 and 1976 in the ruins of the city of Ebla

(Tell Mardikh). The tablets were first translated by Giovanni Pettinato.

Centraal-Semitische talen

Fragment uit een twaalfde eeuwse Koran in het Arabisch

Noordwest-Semitische talen

Kanaänitische talen

o Hebreeuws

o Moabitisch -- uitgestorven

o Edomitisch -- uitgestorven

o Ammonitisch -- uitgestorven

o Fenicisch (en het jongere Punisch) -- uitgestorven

Aramees

o Syrisch

o Mandees

Mandaïsch

Het Mandaïsch of Mandees is de klassieke taal van de mandaeërs, een religieuze minderheid

die voornamelijk in het grensgebied tussen Iran en Irak woont. Hun aantal is kleiner dan

100.000.

Mandaïsch is een dialect van het Aramees, met sterke invloeden van het Perzisch. Het wordt

voornamelijk als liturgische taal gebruikt. De religieuze geschriften van de mandaeërs zijn

opgesteld in deze taal.

Daarnaast heeft zich een moderne, levende neo-Mandaïsche taal ontwikkeld, die door een

kleine groep mandaeërs in en rond Ahvaz (Iran) gesproken wordt.

Ugaritisch -- uitgestorven

Amoritisch -- uitgestorven

Amorite language

The Amorite language is the term used for the early (North-)West Semitic language, spoken

by the north Semitic Amorite tribes prominent in early Middle Eastern history. It is known

exclusively from non-Akkadian proper names recorded by Akkadian scribes during periods of

Amorite rule in Babylonia (end of the 3rd and beginning of the 1st millennium), notably from

Mari, and to a lesser extent Alalakh, Harmal, and Khafaya. Occasionally such names are also

found in early Egyptian texts; and one place-name — "Snir" ()רִנ ְׂש

יfor Mount Hermon — is

known from the Bible (Deut. 3:9).

Arabische talen

Arabisch

Maltees

Zuid-Semitische talen

Westelijk

Ethiopische talen

o Noorden

Ge'ez of Klassiek Ethiopisch -- uitgestorven

Ge'ez

Ge'ez (ግግግ, /gē-ĕz'/, /gŭ'əz/), ook Gi'iz of Ethiopisch genoemd, is een oude AfroAziatische taal die verwant is met het Amhaars en andere moderne Semitische talen die

worden gesproken in Ethiopië en Eritrea. Ge'ez wordt als liturgische taal in de Ethiopischkoptische Kerk nog gebruikt. De taal is echter als spreektaal uitgestorven. In Ethiopië spreekt

men tegenwoordig het Amhaars en het Tigrinya, waarvan het gebruikte schrift een aanpassing

is van het Ge'ez schrift.

Ethiopisch schrift

Genesis in Ge'ez

Het Ethiopisch schrift of het Ge'ez schrift is een abugida schrift en oorspronkelijk

ontwikkeld om het Ge'ez te schrijven, een antieke Semitische taal. In talen die het schrift

gebruiken wordt het "Fidäl" (ግግግ) genoemd, wat "schrift" of "alfabet" betekend.

De belangrijkste talen die het schrift gebruiken zijn het Amhaars in Ethiopië en het Tigrinya

in Eritrea en de Ethiopische regio Tigray. De talen, en dan vooral het Amhaars, gebruiken

gewijzigde vormen van het oorspronkelijke schrift.

Het schrift wordt ook door andere talen in Ethiopië en Eritrea gebruikt, zoals het Tigre,

Harari, Bilin en het Me'en. Enkele andere talen in de Hoorn van Afrika, zoals het Afaan

Oromo werden vroeger ook in het Ethiopisch schrift geschreven, maar zikn op een ander

schriftsysteem over gestapt. Het Afaan Oromo bijvoorbeeld is overgegaan op het Latijns

schrift.

o

Zuiden

Tigrinya of Tigriñña

Tigre

Transverse

Amhaars

Argobba

Harari

Oost-Gurage-talen

Selti

Wolane

Zway

Ulbare

Inneqor

Outer

Soddo

Goggot

Muher

Westelijke Gurage-talen

Masqan

Ezha

Gura

Gyeto

Ennemor

Endegen

Oud-Zuid-Arabische talen -- uitgestorven

o Sabees -- uitgestorven

o Minees -- uitgestorven

o Qatabaans -- uitgestorven

o Hadramitisch -- uitgestorven

Arabisch

o Oud Arabisch

[[Dedanitisch]

Lihyanitisch

Thamudisch

Safaïtisch

o Oud Literair Arabisch: oudste inscriptie: 328 na Christus.

o

Standaard Arabisch + dialecten: vanaf 500

Arabisch

Het Arabisch kent 4 taalperioden:

1. het Oud of Epigrafisch Zuid-Arabisch (afgekort ESA)

2. het Pre-Klassiek Noord-Arabisch

3. het Klassiek Noord-Arabisch, dat "hèt" Arabisch is en dat vanaf de vierde eeuw van de

gewone jaartelling wordt geschreven. Het is een hoogstaand, literair Arabisch. De Koran is in

deze taal geschreven.

4. de Moderne Arabische dialecten die zich hebben ontwikkeld uit het Klassiek Arabisch.

Elk Arabisch land heeft nu zijn eigen Arabisch dialect en de verschillen zijn zo groot dat de

mensen uit de verschillende Arabische landen en regio's elkaar niet of heel moeilijk kunnen

verstaan. Die verschillende dialecten worden (bijna) alleen gesproken en niet geschreven.

Voor het schrijven gebruikt men een soort kunstmatig Arabisch dat Modern Standaard

Arabisch wordt genoemd. Dit is de officiële taal in de gehele Arabische wereld.

Deze taal is afgeleid van het Arabisch van de Koran en wordt in alle Arabische landen op

dezelfde manier geschreven en gesproken. Niemand heeft het MSA als moedertaal. Het is een

taal die op school geleerd wordt. Zodra er Arabisch geschreven moet worden, doet men dit in

het MSA. Wie MSA kan lezen, heeft dus toegang tot kranten, tijdschriften, boeken etc. uit de

hele Arabische wereld. Gesproken wordt het MSA eigenlijk alleen in formele situaties, soms

op TV, bij officiële toespraken etc. Het spreken van MSA is erg moeilijk en slechts een

enkeling beheerst het perfect.

Het Arabische alfabet bestaat uit 28 letters. De schrijfwijze van een letter hangt af van de

plaats waar hij in een woord voorkomt.

Oostelijk

Soqotri

Mehri

Jibbali

Harsusi

Bathari

Hobyot

Gedeelde kenmerken

Deze talen laten allemaal een patroon van woorden bestaande uit drie medeklinkers zien, met

klinkerveranderingen, voorvoegsels en achtervoegsel om ze te verbuigen. Bij voorbeeld, in

het Hebreeuws:

gdl betekent "groot" geen woordklasse of woord, enkel een stam

gadol betekent "groot" en is een mannelijk bijvoeglijk naamwoord

gdola betekent "groot" (vrouwelijk bijvoeglijk naamwoord)

giddel betekent "hij groeide" (overgankelijk werkwoord)

gadal betekent "hij groeide" (onovergankelijk werkwoord)

higdil betekent "hij vergrootte" (overgankelijk werkwoord)

magdelet betekent "vergroter" (lens)

spr is de stam voor "tellen" of "vertellen"

sefer betekent "boek" (bevat verhalen die verteld worden) (' f ' en ' p ' worden in het

Hebreeuws door dezelfde letter weergegeven)

sofer betekent "schrijver" (Masoretische schrijvers vertelden verzen) of "hij telt"

mispar betekent "getal".

Vele stammen worden gedeeld door meer dan een Semitische taal. Bijvoorbeeld, de stam ktb,

een stam die "schrijven" betekent, bestaat zowel in het Hebreeuws als in het Arabisch ("hij

schreef" wordt katav in het Hebreeuws en kataba in Klassiek Arabisch) (ook hier: ' v ' en ' b '

worden door dezelfde letter weergegeven in het Hebreeuws).

De volgende lijst laat een aantal equivalente woorden zien in Semitische talen.

Akkadisch Aramees Arabisch Hebreeuws Nederlandse vertaling

zikaru

dikrā

ḏakar

zåḵår

mannelijk

maliku

malkā

malik

mĕlĕḵ

koning

imêru

ḥamarā

ḥimār

ḥămōr

ezel

erṣetu

ʔarʿā

ʔarḍ

ʔĕrĕṣ

land, aarde

Andere Afro-Aziatische talen laten vergelijkbare patronen zien, maar meestal met stammen

bestaande uit slechts twee medeklinkers. In bijvoorbeeld het Kabylisch betekent afeg "vlieg!",

terwijk affug "vlucht" betekent, en yufeg "hij vloog".

Verschillende kenmerken

Sommige stammen variëren tussen de verschillende Semitische talen. De stam b-y-ḍ

betekent bijvoorbeeld zowel "wit" als "ei" in het Arabisch, terwijl het in het

Hebreeuws alleen "ei" betekent. De stam l-b-n betekent "melk" in het Arabisch, maar

"wit" in het Hebreeuws.

Vanzelfsprekend is er soms geen relatie tussen de stammen. Bijvoorbeeld, "kennis"'

wordt in het Hebreeuws gepresenteerd met de stam y-d-ʿ maar in het Arabisch met de

stammen ʿ-r-f en ʿ-l-m.

De oud-semitische klank [p] bleef behouden in de noordelijke groep, in de zuidelijke

groep evolueerde deze klank tot [f].

In de Noord-Semitische talen worden gezonde meervouden gebruikt, dat wil zeggen

dat de structuur van het woord behouden blijft, en dat het meervoud gevormd wordt

door het toevoegen van een achtervoegsel. In de Zuid-Semitische talen daarentegen

overheersen de gebroken (interne) meervouden. Hierbij verandert de interne

klankstructuur van het woord wel bij het vormen van een meervoud, daarom wordt er

geen achtervoegsel meer aan toegevoegd.

De [w] in het Zuid-Semitisch is in het Noord-Semitisch een [y]. Bv.: "jongen":

[walad] (Arabisch) en [yeled] (Hebreeuws).