Mineralen van Phital

Waardevolle aanvulling voor groei en ontwikkeling

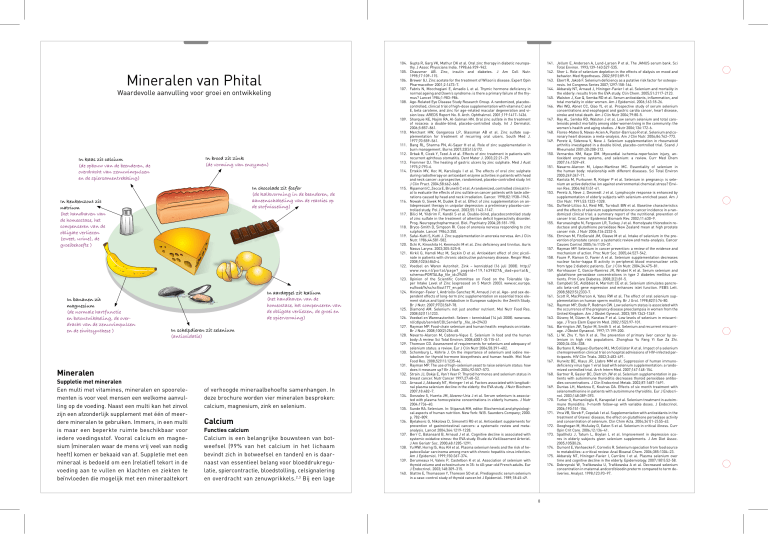

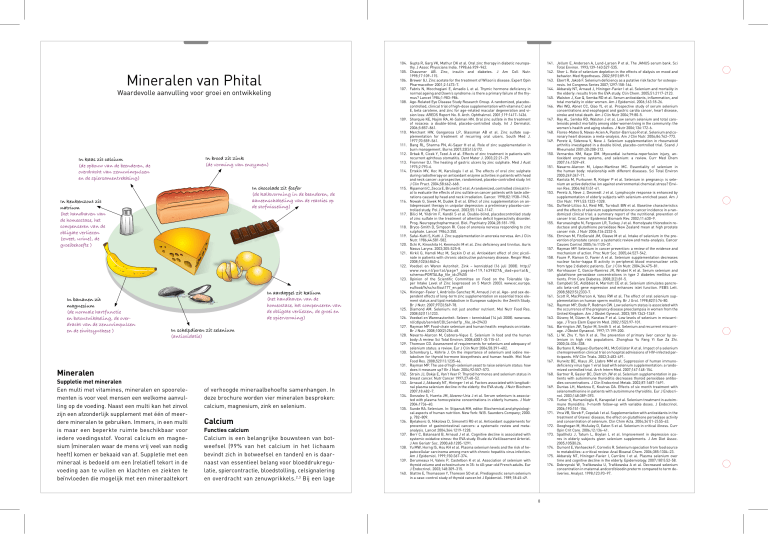

In brood zit zink

(de vorming van enzymen)

In kaas zit calcium

(de opbouw van de beenderen, de

overdracht van zenuwimpulsen

en de spiersamentrekking)

In chocolade zit fosfor

(de kalkvorming in de beenderen, de

aaneenschakeling van de reacties op

de stofwisseling)

In keukenzout zit

natrium

(het handhaven van

de homeostase, het

compenseren van de

obligate verliezen

(zweet, urine), de

groeibehoefte )

In bananen zit

magnesium

(de normale hartfunctie

en botontwikkeling, de overdracht van de zenuwimpulsen

en de eiwitsynthese )

In aardappel zit kalium

(het handhaven van de

homeostase, het compenseren van

de obligate verliezen, de groei en

de spiervorming)

In schelpdieren zit selenium

(antioxidatie)

Mineralen

Suppletie met mineralen

Een multi met vitamines, mineralen en spoorelementen is voor veel mensen een welkome aanvulling op de voeding. Naast een multi kan het zinvol

zijn een afzonderlijk supplement met één of meerdere mineralen te gebruiken. Immers, in een multi

is maar een beperkte ruimte beschikbaar voor

iedere voedingsstof. Vooral calcium en magnesium (mineralen waar de mens vrij veel van nodig

heeft) komen er bekaaid van af. Suppletie met een

mineraal is bedoeld om een (relatief) tekort in de

voeding aan te vullen en klachten en ziekten te

beïnvloeden die mogelijk met een mineraaltekort

of verhoogde mineraalbehoefte samenhangen. In

deze brochure worden vier mineralen besproken:

calcium, magnesium, zink en selenium.

Calcium

Functies calcium

Calcium is een belangrijke bouwsteen van botweefsel (99% van het calcium in het lichaam

bevindt zich in botweefsel en tanden) en is daarnaast van essentieel belang voor bloeddrukregulatie, spiercontractie, bloedstolling, celsignalering

en overdracht van zenuwprikkels. 2,3 Bij een lage

104. Gupta R, Garg VK, Mathur DK et al. Oral zinc therapy in diabetic neuropathy. J Assoc Physicians India. 1998;46:939–942.

105. Chausmer AB. Zinc, insulin and diabetes. J Am Coll Nutr.

1998;17:109–115.

106. Brewer GJ. Zinc acetate for the treatment of Wilson’s disease. Expert Opin

Pharmacother 2001;2:1473–7.

107. Fabris N, Mocchegiani E, Amadio L et al. Thymic hormone deficiency in

normal ageing and Down’s syndrome: is there a primary failure of the thymus? Lancet 1984;1:983–986.

108. Age-Related Eye Disease Study Research Group. A randomized, placebocontrolled, clinical trial of high-dose supplementation with vitamins C and

E, beta carotene, and zinc for age-related macular degeneration and vision loss: AREDS Report No. 8. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2001;119:1417–1436.

109. Sharquie KE, Najim RA, Al-Salman HN. Oral zinc sulfate in the treatment

of rosacea: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Int J Dermatol.

2006;5:857–861.

110. Merchant HW, Gangarosa LP, Glassman AB et al. Zinc sulfate supplementation for treatment of recurring oral ulcers. South Med J.

1977;70:559–561.

111. Bang RL, Sharma PN, Al-Sayer H et al. Role of zinc supplementation in

burn management. Burns 2007;33(S1):S172.

112. Orbak R, Cicek Y, Tezel A et al. Effects of zinc treatment in patients with

recurrent aphthous stomatitis. Dent Mater J. 2003;22:21–29.

113. Frommer DJ. The healing of gastric ulcers by zinc sulphate. Med J Aust

1975;2:793-6.

114. Ertekin MV, Koc M, Karslioglu I et al. The effects of oral zinc sulphate

during radiotherapy on antioxidant enzyme activities in patients with head

and neck cancer: a prospective, randomised, placebo-controlled study. Int

J Clin Pract. 2004;58:662–668.

115. Ripamonti C, Zecca E, Brunelli C et al. A randomized, controlled clinical trial to evaluate the effects of zinc sulfate on cancer patients with taste alterations caused by head and neck irradiation. Cancer. 1998;82:1938–1945.

116. Nowak G, Siwek M, Dudek D et al. Effect of zinc supplementation on antidepressant therapy in unipolar depression: a preliminary placebo-controlled study. Pol J Pharmacol. 2003;55:1143-1147.

117. Bilici M, Yildirim F, Kandil S et al. Double-blind, placebocontrolled study

of zinc sulfate in the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2004;28:181-190.

118. Bryce-Smith D, Simpson RI. Case of anorexia nervosa responding to zinc

sulphate. Lancet 1984;2:350.

119. Safai-Kutti S, Kutti J. Zinc supplementation in anorexia nervosa. Am J Clin

Nutr. 1986;44:581-582.

120. Ochi K, Kinoshita H, Kenmochi M et al. Zinc deficiency and tinnitus. Auris

Nasus Larynx. 2003;30S:S25-8.

121. Kirkil G, Hamdi Muz M, Seçkin D et al. Antioxidant effect of zinc picolinate in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Med.

2008;102(6):840-4.

122. Voedsel en Waren Autoriteit. Zink – kennisblad (16 juli 2008). http://

www.vwa.nl/portal/page?_pageid=119,1639827&_dad=portal&_

schema=PORTAL&p_file_id=29455

123. Opinion of the Scientific Committee on Food on the Tolerable Upper Intake Level of Zinc (expressed on 5 March 2003). www.ec.europa.

eu/food/fs/sc/scf/out177_en.pdf

124. Hininger-Favier I, Andriollo-Sanchez M, Arnaud J et al. Age- and sex-dependent effects of long-term zinc supplementation on essential trace element status and lipid metabolism in European subjects: the Zenith Study.

Br J Nutr. 2007;97(3):569-78.

125. Diamond AM. Selenium: not just another nutrient. Mol Nutr Food Res.

2008;52(11):1233.

126. Voedsel en Warenautoriteit. Seleen – kennisblad (14 juli 2008). www.vwa.

nl/cdlpub/servlet/CDLServlet?p _file_id=29433

127. Rayman MP. Food-chain selenium and human health: emphasis on intake.

Br J Nutr. 2008;100(2):254-68.

128. Navarro-Alarcon M, Cabrera-Vique C. Selenium in food and the human

body: A review. Sci Total Environ. 2008;400(1-3):115-41.

129. Thomson CD. Assessment of requirements for selenium and adequacy of

selenium status: a review. Eur J Clin Nutr 2004;58:391–402.

130. Schomburg L, Köhrle J. On the importance of selenium and iodine metabolism for thyroid hormone biosynthesis and human health. Mol Nutr

Food Res. 2008;52(11):1235-46.

131. Rayman MP. The use of high-selenium yeast to raise selenium status: how

does it measure up? Br J Nutr. 2004;92:557–573.

132. Strain JJ, Bokje E, Van’t Veer P. Thyroid hormones and selenium status in

breast cancer. Nutr Cancer 1997;27:48–52.

133. Arnaud J, Akbaraly NT, Hininger I et al. Factors associated with longitudinal plasma selenium decline in the elderly: the EVA study. J Nutr Biochem

2007;18:482–7.

134. Gonzalez S, Huerta JM, Alvarez-Uria J et al. Serum selenium is associated with plasma homocysteine concentrations in elderly humans. J Nutr

2004:1736–40.

135. Sunde RA. Selenium. In: Stipanuk MH, editor. Biochemical and physiological aspects of human nutrition. New York: W.B. Saunders Company; 2000.

p. 782–809.

136. Bjelakovic G, Nikolova D, Simonetti RG et al. Antioxidant supplements for

prevention of gastrointestinal cancers: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Lancet 2004;364:1219-1228.

137. Berr C, Balansard B, Arnaud J et al. Cognitive decline is associated with

systemic oxidative stress: the EVA study. Etude du Vieillissement Arteriel.

J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:1285-1291.

138. Yu MW, Horng IS, Hsu KH et al. Plasma selenium levels and the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma among men with chronic hepatitis virus infection.

Am J Epidemiol. 1999;150:367-374.

139. Derumeaux H, Valeix P, Castetbon K et al. Association of selenium with

thyroid volume and echostructure in 35- to 60-year-old French adults. Eur

J Endocrinol. 2003;148:309–315.

140. Glattre E, Thomassen Y, Thoresen SO et al. Prediagnostic serum selenium

in a case–control study of thyroid cancer.Int J Epidemiol. 1989;18:45-49.

141. Jellum E, Andersen A, Lund-Larsen P et al. The JANUS serum bank. Sci

Total Environ. 1993;139-140:527-535.

142. Sher L. Role of selenium depletion in the effects of dialysis on mood and

behavior. Med Hypotheses. 2002;59(1):89-91.

143. Ebert R, Jakob F. Selenium deficiency as a putative risk factor for osteoporosis. Int Congress Series 2007;1297:158-164.

144. Akbaraly NT, Arnaud J, Hininger-Favier I et al. Selenium and mortality in

the elderly: results from the EVA study. Clin Chem. 2005;51:2117-2123.

145. Walston J, Xue Q, Semba RD et al. Serum antioxidants, inflammation, and

total mortality in older women. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163:18-26.

146. Wei WQ, Abnet CC, Qiao YL et al. Prospective study of serum selenium

concentrations and esophageal and gastric cardia cancer, heart disease,

stroke and total death. Am J Clin Nutr 2004;79:80-5.

147. Ray AL, Semba RD, Walston J et al. Low serum selenium and total carotenoids predict mortality among older women living in the community: the

women’s health and aging studies. J Nutr 2006;136:172-6.

148. Flores-Mateo G, Navas-Acien A, Pastor-Barriuso R et al. Selenium and coronary heart disease: a meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84:762–773.

149. Peretz A, Siderova V, Neve J. Selenium supplementation in rheumatoid

arthritis investigated in a double blind, placebo-controlled trial. Scand J

Rheumatol 2001;30:208-212.

150. Vernardos KM, Kaye DM. Myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury, antioxidant enzyme systems, and selenium: a review. Curr Med Chem

2007;14:1539–49.

151. Navarro-Alarcon M, López-Martínez MC. Essentiality of selenium in

the human body: relationship with different diseases. Sci Total Environ

2000;249:347–71.

152. Kantola M, Purkunen R, Kröger P et al. Selenium in pregnancy: is selenium an active defective ion against environmental chemical stress? Environ Res. 2004;96(1):51-61.

153. Peretz A, Neve J, Desmedt J et al. Lymphocyte response is enhanced by

supplementation of elderly subjects with selenium-enriched yeast. Am J

Clin Nutr. 1991;53:1323-1328.

154. Duffield-Lillico AJ, Reid ME, Turnbull BW et al. Baseline characteristics

and the effects of selenium supplementation on cancer incidence in a randomized clinical trial: a summary report of the nutritional prevention of

cancer trial. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Rev. 2002;11:630–9.

155. Karunasinghe N, Ferguson LR, Tuckey J et al. Homolysate thioredoxin reductase and glutathione peroxidase New Zealand mean at high prostate

cancer risk. J Nutr 2006;136:2232-5.

156. Etminan M, FitzGerald JM, Gleave M et al. Intake of selenium in the prevention of prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer

Causes Control 2005;16:1125–31.

157. Rayman MP. Selenium in cancer prevention: a review of the evidence and

mechanism of action. Proc Nutr Soc. 2005;64:527-542.

158. Faure P, Ramon O, Favier A et al. Selenium supplementation decreases

nuclear factor-kappa B activity in peripheral blood mononuclear cells

from type 2 diabetic patients. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2004;34:475–81.

159. Kornhauser C, Garcia-Ramirez JR, Wrobel K et al. Serum selenium and

glutathione peroxidase concentrations in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients. Prim Care Diabetes. 2008;2(2):81-5.

160. Campbell SC, Aldibbiat A, Marriott CE et al. Selenium stimulates pancreatic beta-cell gene expression and enhances islet function. FEBS Lett.

2008;582(15):2333-7.

161. Scott R, MacPherson A, Yates RW et al. The effect of oral selenium supplementation on human sperm motility. Br J Urol. 1998;82(1):76-80.

162. Rayman MP, Bode P, Redman CW. Low selenium status is associated with

the occurrence of the pregnancy disease preeclampsia in women from the

United Kingdom. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189:1343-1349.

163. Güvenç M, Güven H, Karatas F et al. Low levels of selenium in miscarriage. J Trace Elem Experim Med. 2002;15(2):97-101.

164. Barrington JW, Taylor M, Smith S et al. Selenium and recurrent miscarriage. J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;17:199-200.

165. Li W, Zhu Y, Yan X et al. The prevention of primary liver cancer by selenium in high risk populations. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi.

2000;34:336–338.

166. Burbano X, Miguez-Burbano MJ, McCollister K et al. Impact of a selenium

chemoprevention clinical trial on hospital admissions of HIV-infected participants. HIV Clin Trials. 2002;3:483-491.

167. Hurwitz BE, Klaus JR, Llabre MM et al. Suppression of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 viral load with selenium supplementation: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:148-154.

168. Gartner R, Gasier BC, Dietrich JW et al. Selenium supplementation in patients with autoimmune thyroiditis decreases thyroid peroxidase antibodies concentrations. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:1687-1691.

169. Duntas LH, Mantzou E, Koutras DA. Effects of six month treatment with

selenomethionine in patients with autoimmune thyroiditis. Eur J Endocrinol. 2003;148:389–393.

170. Turker O, Kumanlioglu K, Karapolat I et al. Selenium treatment in autoimmune thyroiditis: 9-month follow-up with variable doses. J Endocrinol.

2006;190:151-156.

171. Vrca VB, Skreb F, Cepelak I et al. Supplementation with antioxidants in the

treatment of Graves’ disease; the effect on glutathione peroxidase activity

and concentration of selenium. Clin Chim Acta. 2004;341(1-2):55-63.

172. Geoghegan M, McAuley D, Eaton S et al. Selenium in critical illness. Curr

Opin Crit Care. 2006;12:136–41.

173. Spallholz J, Tatum L, Boylan L et al. Improvement in depression scores in elderly subjects given selenium supplements. J Am Diet Assoc.

2005;105(8):26.

174. Dumont E, Vanhaecke F, Cornelis R. Selenium speciation from food source

to metabolites: a critical review. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2006;385:1304–23.

175. Akbaraly NT, Hininger-Favier I, Carrière I et al. Plasma selenium over

time and cognitive decline in the elderly. Epidemiology. 2007;18(1):52-58.

176. Dobrzynski W, Trafikowska U, Trafikowska A et al. Decreased selenium

concentration in maternal andcord bloodin preterm compared to term deliveries. Analyst. 1998;123:93–97.

8

Mogelijke toepassingen voor calciumsuppletie

genoemd in wetenschappelijke literatuur:

• Lage inname van calcium uit voeding (mijden

van zuivel).

• Gebruik van medicijnen die de calciumbehoefte

verhogen waaronder anticonvulsiva (phenytoïne, fenobarbital, carbamazepine), corticosteroïden en lisdiuretica.17-19

• Darmaandoeningen: inflammatoire darmziekten en coeliakie gaan gepaard met verminderde

opname van calcium en/of vitamine D en/of verlies van calcium via calciumbevattende darm­

epitheelcellen.20

• Preventie (en behandeling) osteoporose en botbreuken: een calciuminname (uit voeding en

supplementen) van 1300–1700 mg/dag stopt

leeftijdsgerelateerde botafname en verlaagt de

kans op botbreuken bij ouderen boven 65 jaar

beter dan de aanbevolen calciuminname van

1200 mg/dag.21 Suppletie met 1200 mg calcium

per dag gedurende 4 jaar zorgde voor significante verlaging van de kans op botbreuken bij

oudere proefpersonen. 22 Het aanbieden van

voldoende calcium tijdens de groeispurt van

kinderen helpt bij het bereiken van een hoge

piekbotmassa en is een goede strategie om de

kans op leeftijdsgerelateerde osteoporose te

verkleinen.23,24

• Hypertensie (preventie): calciumsuppletie heeft

mogelijk een licht bloeddrukverlagend effect bij

hypertensie, met name bij een lage calciuminname uit voeding (‹ 800 mg/dag).2,9 Nog belangrijker is dat verbetering van de calciuminname

(maar ook de kalium en magnesium inname) via

een verhoogde consumptie van fruit en groenten de bloeddruk verbetert.10

• Calciumsuppletie lijkt het risico van preeclampsie te verminderen.25

• Diabetes type 2: een optimale inname van calcium (en vitamine D) kan de glycemische controle verbeteren.26

• Premenstrueel syndroom (PMS): suppletie met

1000-1200 mg calcium per dag kan de ernst van

PMS-klachten (stemmings- en gedragsveranderingen, pijn, vochtretentie) met 50% verlagen.7,11

• Calcium speelt mogelijk een rol bij Polycysteuze ovaria.3,27

• Overgewicht: mensen met overgewicht hebben

40% meer kans obees te worden wanneer hun

calciuminname laag is.28

calciuminname uit voeding wordt calcium aan de

botten onttrokken en neemt de renale uitscheiding

van calcium af om de calciumbloedspiegel constant te houden. Vitamine D bevordert de calcium­

absorptie en –depositie; vitamine K2 bevordert de

afzetting van calcium in botweefsel en gaat verkalking van zachte weefsels (bloedvaten, nieren etc.)

tegen.4

Verlaagde calciumstatus

Veel Nederlanders hebben een suboptimale calciuminname. 5,6 Volgens de Gezondheidsraad

bedraagt de adequate inneming van calcium voor

1-3 jaar: 500 mg/dag; 4-8 jaar: 700 mg/d; 9-18 jaar:

1100 mg/dag (jongens) en 1200 mg/d (meisjes);

19-50 jaar: 1000 mg/dag; 51-70 jaar: 1100 mg/dag

en › 70 jaar: 1200 mg/dag.5 De feitelijke (gemiddelde) calciuminname is voor veel groepen (meisjes/vrouwen boven 9 jaar, mannen tussen 9-18 jaar

en boven 70 jaar) 100-300 mg/dag onder de norm.6

Dit zijn gemiddelde innamen: mensen die geen

zuivel consumeren hebben over het algemeen

grote moeite dagelijks de aanbevolen hoeveelheid calcium binnen te krijgen. Melk(producten) en

kaas vormen de belangrijkste bron van calcium in

Nederlandse voeding en leveren circa 70% van het

benodigde calcium. Andere bronnen van calcium

zijn groenten, bonen, noten en zaden. De huidige

aanbevelingen zijn mogelijk te laag voor een optimale calciumstatus en calciumgerelateerde ziektepreventie, met name bij ouderen.3

Hypocalcemie kan zich onder meer uiten in klachten

als vermoeidheid, angst, neerslachtigheid, geheugenproblemen, prikkelbaarheid en spierkrampen.7

Een lage calciuminname leidt tot afname van de

botmineraaldichtheid, waardoor sneller botbreuken optreden, en is mogelijk geassocieerd met een

verhoogd risico op metabool syndroom, overgewicht/obesitas, hoge bloeddruk, hypercholesterolemie, pre-eclampsie, premenstrueel syndroom,

osteoporose en (darm)kanker. 3,8-14,21 Kinderen die

langdurig geen zuivel consumeren, blijven kleiner

en bouwen een minder sterk skelet op.15

Bepalen calciumstatus

Er is (nog) geen goede functionele marker voor het

bepalen van de calciumstatus. De calciumstatus

kan het beste worden afgeleid uit de calciuminname uit voeding en voedingssupplementen.16

2

37. Schulze MB., Schulz M, Heidemann C et al. Fiber and magnesium intake

and incidence of type 2 diabetes: a prospective study and meta-analysis.

Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:956–965.

38. McKeown NM, Jacques PF, Zhang XL et al. Dietary magnesium intake is related to metabolic syndrome in older Americans. Eur J Nutr.

2008;47(4):210-6.

39. Rodríguez-Hernández H, Gonzalez JL, Rodríguez-Morán M et al. Hypomagnesemia, insulin resistance, and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in

obese subjects. Arch Med Res. 2005;36(4):362-6.

40. Barbagallo M, Dominguez LJ. Magnesium metabolism in type 2 diabetes

mellitus, metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2007;458(1):40-7.

41. Fung TT, Manson JE, Solomon CG et al. The association between magnesium intake and fasting insulin concentration in healthy middle-aged

women. J Am Coll Nutr. 2003;22(6):533-8.

42. Resnick LM, Barbagallo M, Bardicef M et al. Cellular-free magnesium

depletion in brain and muscle of normal and preeclamptic pregnancy: a nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopic study. Hypertension.

2004;44:322–326.

43. Sibai BM. Diagnosis, prevention, and management of eclampsia. Obstet

Gynecol. 2005;105(2):402-10.

44. Champagne CM. Magnesium in hypertension, cardiovascular disease,

metabolic syndrome, and other conditions: a review. Nutr Clin Pract.

2008;23(2):142-51.

45. Gontijo-Amaral C, Ribeiro MA, Gontijo LS et al. Oral magnesium supplementation in asthmatic children: a double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trial. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2007;61(1):54-60.

46. Tsai CJ, Leitzmann MF, Willett WC et al. Long-term effect of magnesium

consumption on the risk of symptomatic gallstone disease among men.

Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103(2):375-82.

47. Hantoushzadeh S, Jafarabadi M, Khazardoust S. Serum magnesium levels, muscle cramps, and preterm labor. Int J Gynaecol Obstet.

2007;98(2):153-4.

48. Disorders of Magnesium Metabolism. J Int Fed Clin Chem.

1999;11(2):10-18.

49. Arnaud MJ. Update on the assessment of magnesium status. Br J Nutr.

2008;99(S3):S24-36.

50. Gupta A, Eastham KM, Wrightson N et al. Hypomagnesaemia in cystic fibrosis patients referred for lung transplant assessment. J Cyst Fibros.

2007;6(5):360-2.

51. Schrag D, Chung KY, Flombaum C et al. Cetuximab therapy and symptomatic hypomagnesemia. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97(16):1221-4.

52. Rodríguez-Morán M, Guerrero-Romero F. Oral magnesium supplementation improves insulin sensitivity and metabolic control in type 2 diabetic subjects: a randomized double-blind controlled trial. Diabetes Care.

2003;26(4):1147-52.

53. Yokota K, Kato M, Lister F et al. Clinical efficacy of magnesium supplementation in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Am Coll Nutr.

2004;23:506S–509S.

54. Song Y, He K, Levitan EB et al. Effects of oral magnesium supplementation on glycaemic control in Type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of randomized

double-blind controlled trials. Diabet Med. 2006;23:1050–1056.

55. Rodríguez-Morán M, Guerrero-Romero F. Low serum magnesium levels and foot ulcers in subjects with type 2 diabetes. Arch Med Res.

2001;32(4):300-3.

56. Paolisso G, Sgambato S, Gambardella A et al. Daily magnesium supplements improve glucose handling in elderly subjects. Am J Clin Nutr.

1992;55:1161–1167.

57. Rude RK, Gruber HE. Magnesium deficiency and osteoporosis: animal and

human observations. J Nutr Biochem. 2004;15(12):710-6.

58. Ryder KM, Shorr RI, Bush AJ et al. Magnesium intake from food and supplements is associated with bone mineral density in healthy older white

subjects. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(11):1875-80.

59. Lukaski HC. Magnesium, zinc, and chromium nutriture and physical activity. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;72(2 Suppl):585S-93S.

60. Shechter M, Bairey Merz CN, Stuehlinger HG et al. Effects of oral magnesium therapy on exercise tolerance, exercise-induced chest pain, and

quality of life in patients with coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol.

2003;91(5):517-21.

61. Shechter M, Merz CN, Paul-Labrador M et al. Oral magnesium supplementation inhibits platelet-dependent thrombosis in patients with coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 1999;84(2):152-6.

62. Lichodziejewska B, Kłoś J, Rezler J et al. Clinical symptoms of mitral

valve prolapse are related to hypomagnesemia and attenuated by magnesium supplementation. Am J Cardiol. 1997;79(6):768-72.

63. Stepura OB, Martynow AI. Magnesium orotate in severe congestive heart

failure (MACH). Int J Cardiol. 2008 Feb 15.

64. Almoznino-Sarafian D, Berman S, Mor A et al. Magnesium and C-reactive

protein in heart failure: an anti-inflammatory effect of magnesium administration? Eur J Nutr. 2007;46(4):230-7.

65. Fuentes JC, Salmon AA, Silver MA. Acute and chronic oral magnesium

supplementation: effects on endothelial function, exercise capacity, and

quality of life in patients with symptomatic heart failure. Congest Heart

Fail. 2006;12(1):9-13.

66. Kawano Y, Matsuoka H, Takishita S et al. Effects of magnesium supplementation in hypertensive patients: assessment by office, home, and ambulatory blood pressures. Hypertension. 1998;32(2):260-5.

67. Sanjuliani AF, de Abreu Fagundes VG, Francischetti EA. Effects of magnesium on blood pressure and intracellular ion levels of Brazilian hypertensive patients. Int J Cardiol. 1996;56(2):177-83.

68. Sontia B, Touyz RM. Role of magnesium in hypertension. Arch Biochem

Biophys. 2007;458(1):33-9.

69. Quaranta S, Buscaglia MA, Meroni MG, Colombo E, Cella S. Pilot study of

the efficacy and safety of a modified-release magnesium 250 mg tablet

(Sincromag) for the treatment of premenstrual syndrome. Clin Drug Investig. 2007;27(1):51-8.

70. De Souza MC, Walker AF, Robinson PA et al. A synergistic effect of a daily

supplement for 1 month of 200 mg magnesium plus 50 mg vitamin B6

for the relief of anxiety-related premenstrual symptoms: a randomized, double-blind, crossover study. J Womens Health Gend Based Med.

2000;9(2):131-9.

71. Mauskop A. Complementary and Alternative Treatments for Migraine.

Drug Development Research 2007;68:424–427.

72. Aziz HS, Blamoun AI, Shubair MK et al. Serum magnesium levels and acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a retrospective

study. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2005;35(4):423-7.

73. Maret W, Sandstead HH. Zinc requirements and the risks and benefits of

zinc supplementation. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2006;20(1):3-18.

74. Salgueiro MJ, Zubillaga M, Lysionek A et al. Zinc as an essential micronutrient: a review. Nutr Res. 2000;20(5):737-755.

75. Rink L, Haase H. Zinc homeostasis and immunity. Trends Immunol.

2007;28,:1–4.

76. Voedingscentrum.nl / EtenEnGezondheid / Voedingstoffen / vitamines + en

+ mineralen

77. Hyun TH, Barrett-Connor E, Milne DB. Zinc intakes and plasma concentrations in men with osteoporosis: the Rancho Bernardo Study. Am J Clin

Nutr 2004;80:715-21.

78. Pilz S, Dobnig H, Winklhofer-Roob BM et al. Low serum zinc concentrations predict mortality in patients referred to coronary angiography. Br J

Nutr. 2008:1-7.

79. Ho E. Zinc deficiency, DNA damage and cancer risk. J Nutr Biochem.

2004;15(10):572-8.

80. Golik A, Zaidensttein R, Dishi V et al. Effects of captopril and enalapril on

zinc metabolism in hypertensive patients. J Am Coll Nutr 1998;17:75-8.

81. Neuvonen PJ. Interactions with the absorption of tetracyclines. Drugs

1976;11(1):45-54.

82. Peretz A, Neve J, Famaey JP. Effects of chronic and acute corticosteroid

therapy on zinc and copper status in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Trace

Elem Electrolytes Health Dis 1989;3(2):103-8.

83. Murry JJ, Healy MD. Drug-mineral interactions: a new responsibility for

the hospital dietician. J Am Diet Assoc 1991;91(1):66-73.

84. Herzberg M, Lusky A, Blonder J et al. The effect of estrogen replacement

therapy on zinc in serum and urine. Obstet Gynecol 1996;87:1035–40.

85. Sturniolo GC, Montino MC, Rossetto L et al. Inhibition of gastric acid secretion reduces zinc absorption in man. J Am Coll Nutr 1991;10(4):372-5.

86. Haase H, Mocchegiani E, Rink L. Correlation between zinc status and immune function in the elderly. Biogerontology 2006;7:421–428.

87. Prasad AS, Beck FW, Bao B et al. Zinc supplementation decreases incidence of infections in the elderly: effect of zinc on generation of cytokines

and oxidative stress. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85(3):837-44.

88. Hulisz, D. Efficacy of zinc against common cold viruses: an overview. J Am

Pharm Assoc. 2004;44:94–603.

89. Fischer Walker C, Black RE. Zinc and the risk for infectious disease. Annu

Rev Nutr. 2004;24:255–275.

90. Lukacik M, Thomas RL, Aranda JV. A meta-analysis of the effects of

oral zinc in the treatment of acute and persistent diarrhea. Pediatrics.

2008;121(2):326-36.

91. Sazawal S, Black RE, Jalla S et al. Zinc supplementation reduces the

incidence of acute lower respiratory infections in infants and preschool

children: a doubleblind, controlled trial. Pediatrics. 1998;102:1–5.

92. Mahalanabis D, Lahiri M, Paul D et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebocontrolled clinical trial of the efficacy of treatment with zinc or vitamin

A in infants and young children with severe acute lower respiratory infection. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79:430–436.

93. Karyadi E, West CE, Schultink W et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled

study of vitamin A and zinc supplementation in persons with tuberculosis

in Indonesia: effects on clinical response and nutritional status. Am J Clin

Nutr. 2002;75:720–727.

94. Duggan C, MacLeod WB, Krebs NF et al. Plasma zinc concentrations are

depressed during the acute phase response in children with falciparum

malaria. J Nutr. 2005;135:802–807.

95. Shankar AH, Genton B, Baisor M et al. The influence of zinc supplementation on morbidity due to Plasmodium falciparum: a randomized

trial in preschool children in Papua New Guinea. Am J Trop Med Hyg.

2000;62:663–669.

96. Muller O, Becher H, van Zweeden AB et al. Effect of zinc supplementation

on malaria and other causes of morbidity in west African children: randomised double blind placebo controlled trial. BMJ 2001;322:1567.

97. Van Weyenbergh J, Santana G, D’Oliveira Jr A et al. Zinc/copper imbalance

reflects immune dysfunction in human leishmaniasis: an ex vivo and in

vitro study. BMC Infect Dis. 2004;4:50.

98. Prasad AS, Schoomaker EB, Ortega J et al. Zinc deficiency in sickle cell

disease. Clin Chem. 1975;21:582–587.

99. Stamoulis I, Kouraklis G, Theocharis S. Zinc and the liver: an active interaction. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52(7):1595-612.

100. Zoli A, Altomonte L, Caricchio R et al. Serum zinc and copper in active

rheumatoid arthritis: correlation with interleukin 1 beta and tumour necrosis factor alpha. Clin Rheumatol. 198;17:378–382.

101. Clemmensen OJ, Siggaard-Andersen J, Worm AM et al. Psoriatic arthritis

treated with oral zinc sulphate. Br J Dermatol. 1980;103:411–415.

102. Roussel AM, Kerkeni A, Zouari N et al. Antioxidant effects of zinc supplementation in Tunisians with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Am Coll Nutr

2003;22:316–21.

103. Faure P, Benhamou PY, Perard A et al. Lipid peroxidation in insulin dependant diabetic patients with early retinal degenerative lesions: effect of an

oral zinc supplementation. Eur J Clin Nutr 1995;49:282–8.

7

Mogelijke toepassingen voor seleniumsuppletie

genoemd in wetenschappelijke onderzoeken:

Er zijn aanwijzingen dat een goede seleniumstatus bijdraagt aan de preventie en remming van

leeftijdsgerelateerde degeneratieve aandoeningen.128,135,144-147

Seleniumsuppletie kan een rol spelen bij:

• Lage inname van selenium uit voeding.128

• Verhoogde seleniumbehoefte bij ziekten die

gepaard gaan met toename van oxidatieve

stress (onder meer astma, reumatoïde artritis,

hart- en vaatziekten, ontstekingsziekten, infectieziekten).127,128,149-151

• Zware metalenbelasting (kwik, lood, cadmium),

leverziekten, roken.127,128,152

• Verminderde weerstand bij ouderen.127,153

• Diabetes: preventie micro- en macrovasculaire

diabetescomplicaties158 waaronder diabetische

nefropathie159, ondersteuning functie eilandjes

van Langerhans.160

• Verminderd vruchtbare mannen met een lage

selenium status. Selenium zou de spermamotiliteit kunnen verbeteren en daarmee de kans

op een succesvolle conceptie .161

• Zwangerschap: een lage seleniumstatus is

geassocieerd met pre-eclampsie162 , miskraam163,164 en vroeggeboorte176; Selenium zou

een actieve rol kunnen spelen bij de bescherming van moeder en kind tegen milieutoxines152

• Virale infecties127: verhoging van de seleniumstatus kan de kans op leverkanker bij patiënten

met hepatitis B/C verlagen127,138,165; verhoging

van de seleniumstatus verbetert de prognose

bij een HIV-infectie.127,166,167

• Kritieke ziekte (trauma, sepsis, brandwonden,

ARDS).172

• Depressie (vooral bij een suboptimale seleniumstatus).142,173

Referenties

1.

2.

3.

4.

5. 6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21. 22. 23. 24. 25. 26. 27. Dosering en veiligheid

De Scientific Committee for Food heeft een aanvaardbare bovengrens voor inname (UL=upper

limit) van 300 microgram per dag voor volwassenen vastgesteld. Deze bovengrens geldt ook voor

zwangere en zogende vrouwen.126 In de Verenigde

Staten geldt een UL van 400 mcg per dag.128 Seleniummethionine, een organisch gebonden vorm van

selenium die in voeding voorkomt, heeft een hoge

biologische beschikbaarheid en wordt veel beter

opgenomen dan anorganische vormen zoals natriumseleniet.128,174,175 Langdurige inname van selenium (uit voeding en voedingsupplementen) boven

de UL-waarde moet worden vermeden.

28. 29. 30. 31. 32. 33. 34. 35. 36. 6

Haase H, Overbeck S, Rink L. Zinc supplementation for the treatment or

prevention of disease: current status and future perspectives. Exp Gerontol. 2008;43(5):394-408.

van Mierlo LA, Arends LR, Streppel MT et al. Blood pressure response to

calcium supplementation: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Hum Hypertens. 2006;20(8):571-80.

Heaney RP. Calcium intake and disease prevention. Arq Bras Endocrinol

Metabol. 2006;50(4):685-93.

Adams J, Pepping J. Vitamin K in the treatment and prevention of

osteoporosis and arterial calcification. Am J Health Syst Pharm.

2005;62(15):1574-81.

Gezondheidsraad. Voedingsnormen: calcium, vitamine D, thiamine, riboflavine, niacine, pantotheenzuur en biotine. Den Haag: Gezondheidsraad,

2000;publicatie nr 2000/12.

Zo eet Nederland: resultaten van de Voedselconsumptiepeiling 19971998. Den Haag: Voedingscentrum, 1998.

Thys-Jacobs S. Micronutrients and the premenstrual syndrome: the case

for calcium. J Am Coll Nutr. 2000;19(2):220-7.

Jorde R, Sundsfjord J, Haug E et al. Relation between low calcium

intake, parathyroid hormone, and blood pressure. Hypertension.

2000;35(5):1154-9.

Dwyer JH, Dwyer KM, Scribner RA et al. Dietary calcium, calcium supplementation, and blood pressure in African American adolescents. Am J

Clin Nutr. 1998 Sep;68(3):648-55.

Houston MC, Harper KJ. Potassium, magnesium, and calcium: their role

in both the cause and treatment of hypertension. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2008;10(7 Suppl 2):3-11.

Bertone-Johnson ER, Hankinson SE, Bendich A et al. Calcium and vitamin

D intake and risk of incident premenstrual syndrome. Arch Intern Med.

2005;165(11):1246-52.

Jacqmain M, Doucet E, Després JP et al. Calcium intake, body composition, and lipoprotein-lipid concentrations in adults. Am J Clin Nutr.

2003;77(6):1448-52.

DeJongh ED, Binkley TL, Specker BL. Fat mass gain is lower in calciumsupplemented than in unsupplemented preschool children with low dietary calcium intakes. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84(5):1123-7.

Lappe JM, Travers-Gustafson D, Davies KM et al. Vitamin D and calcium

supplementation reduces cancer risk: results of a randomized trial. Am J

Clin Nutr. 2007;85(6):1586-91.

Black RE, Williams SM, Jones IE et al. Children who avoid drinking cow

milk have low dietary calcium intakes and poor bone health. Am J Clin

Nutr. 2002;76(3):675-80.

Theobald HE. Dietary calcium and health. British Nutrition Foundation

Nutrition Bulletin 2005;30:237-277.

Gough H, Goggin T, Bissessar A et al. A comparative study of the relative

influence of different anticonvulsant drugs, UV exposure and diet on vitamin D and calcium metabolism in out-patients with epilepsy. Q J Med.

1986;59(230):569-77.

Reid IR, Ibbertson HK. Calcium supplements in the prevention of steroidinduced osteoporosis. Am J Clin Nutr. 1986;44(2):287-90.

Friedman PA, Bushinsky DA. Diuretic effects on calcium metabolism. Semin Nephrol. 1999;19(6):551-6.

Abrams SA, O’Brien KO. Calcium and bone mineral metabolism in children with chronic illnesses. Annu Rev Nutr. 2004;24:13-32.

Heaney RP. Calcium needs of the elderly to reduce fracture risk. J Am

Coll Nutr. 2001;20(2S): 192S-197S.

Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Rees JR, Grau MV et al. Effect of calcium supplementation on fracture risk: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. Am J

Clin Nutr. 2008;87(6):1945-51.

Heaney RP, Abrams S, Dawson-Hughes B et al. Peak bone mass. Osteoporos Int. 2000;11:985–1009.

Bailey DA, Martin AD, McKay AA et al. Calcium accretion in girls

and boys during puberty: A longitudinal analysis. J Bone Miner Res.

2000;15:2245–2250.

Hofmeyr G, Duley L, Atallah A. Dietary calcium supplementation for prevention of pre-eclampsia and related problems: a systematic review and

commentary. BJOG 2007;114:933–943.

Pittas AG, Lau J, Hu FB et al. The role of vitamin D and calcium in type 2

diabetes. A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab.

2007;92(6):2017-29.

Thys-Jacobs S. Polycystic ovary syndrome and reproduction. In: Weaver

CM, Heaney RP, eds. Calcium in Human Health. New Jersey: Humana

Press, 2006. pp. 341-55.

Pereira MA, Jacobs DR, Van Horn L et al. Dairy consumption, obesity,

and the insulin resistance syndrome in young adults. J Am Med Assoc

2002;287:2081-9.

Zemel MB, Thompson W, Milstead A et al. Calcium and dairy acceleration

of weight and fat loss during energy restriction in obese adults. Obes Res

2004;12:582-90.

Zemel MB, Richard J, Mathis S et al. Dairy augmentation of total and central fat loss in obese subjects. Int J Obesity 2005;29:391-7.

Bowen J, Noakes M, Clifton PM. A high dairy protein, high-calcium diet

minimizes bone turnover in overweight adults during weight loss. J Nutr.

2004;134(3):568-73.

Kennisbank Voedselveiligheid VWA. Kennisblad magnesium (15 juli 2008).

http://www.vwa.nl/portal/page?_pageid=119,1639827&_dad=portal&_

schema=PORTAL&p_file_id=29412

Rude RK. Magnesium deficiency: a cause of heterogeneous disease in humans. J Bone Miner Res. 1998;13(4):749-58.

Vormann J. Magnesium: nutrition and metabolism. Mol Aspects Med.

2003;24(1-3):27-37.

Fawcett WJ, Haxby EJ, Male DA. Magnesium: physiology and pharmacology. Br J Anaesth. 1999;83(2):302-20.

Evangelopoulos AA, Vallianou NG, Panagiotakos DB et al. An inverse relationship between cumulating components of the metabolic syndrome and

serum magnesium levels. Nutrition Research 2008;28:659–663.

• Afvallen: calciumsuppletie tijdens afvallen

helpt botafbraak tegen te gaan kan de effectiviteit van het dieet verhogen.3,29-31

• Het verbeteren van de calcium status vermindert de kans op verschillende kankersoorten

bij postmenopauzale vrouwen.14

Magnesiumdepletie kan leiden tot een veelheid

van klachten als gebrek aan eetlust, misselijkheid, (chronische) vermoeidheid, verminderde

concentratie, nervositeit, geïrriteerdheid, toegenomen stressgevoeligheid, hartritmestoornissen,

duizeligheid, (spannings)hoofdpijn, spierkramp,

gespannen spieren, spierzwakte, tremoren, bronchiale hyperreactiviteit en afname van de longfunctie. Magnesiumdepletie is daarnaast mogelijk geassocieerd met een toegenomen kans op

overgewicht/obesitas, hypertensie, dyslipidemie,

insulineresistentie, metabool syndroom, diabetes

type 2, ischemische hartziekte, hartfalen, hartritmestoornissen, acute hartdood, osteoporose,

niet-alcoholische leververvetting, mentale problemen (depressie, psychose), migraine, astma,

zwangerschapsproblemen (pre-eclampsie, vroeggeboorte), symptomatische galstenen en convulsies. 33-48 Magnesiumdepletie leidt tot verstoring

van de vitamine D-stofwisseling en/of vitamine Dactiviteit, kaliumdepletie en calciumdepletie (door

afname van de secretie van parathormoon); een

kalium- of calciumsupplement heeft onvoldoende

effect als de magnesiumstatus verlaagd is.33

Dosering en veiligheid

De Gezondheidsraad heeft de aanvaardbare bovengrens van inname van calcium (uit voeding en voedingssupplementen) vastgesteld op 2500 mg/dag

(vanaf 1-jarige leeftijd).5 Dit betekent dat suppletie

met (maximaal) 1000-1500 mg calcium per dag,

naast (niet met calcium verrijkte) voeding voor de

meeste mensen geen problemen oplevert.

Magnesium

Functies magnesium

In het lichaam fungeert magnesium vooral als

(essentiële) co-factor van honderden enzymen, die

onder meer betrokken zijn bij de energieproductie,

celsignalering, glucose-, insuline- en lipidenstofwisseling, DNA-transcriptie, celdeling en eiwit- en

nucleïnezuursynthese. 32,33 Magnesium heeft een

stabiliserend en beschermend effect op membranen en is belangrijk voor de zenuwgeleiding, vaaten spiertonus, antioxidantbescherming, afweer,

hormoonhuishouding, opbouw van botten en tanden, natrium-, kalium-, calciumbalans en vitamine

D-stofwisseling.

Bepalen magnesiumstatus

Slechts 1% van het magnesium bevindt zich in

de extracellulaire ruimte, de rest bevindt zich in

lichaamscellen en botweefsel. Met het bepalen van

het magnesiumgehalte in serum kan alleen een

ernstig magnesiumtekort worden vastgesteld. 33

Een beter beeld van de magnesiumstatus geeft de

magnesiumbelastingstest.49

Verlaagde magnesiumstatus

De gehaltes van magnesium in levensmiddelen

lopen aanzienlijk uiteen. Magnesiumbronnen zijn

onder meer cacao, garnalen, groene groenten,

noten, peulvruchten, zuivel en (volkoren)granen.

De ADH voor magnesium is 250-300 mg/dag voor

vrouwen en 300-350 mg/dag voor mannen. De

geschatte inname van magnesium in Nederland

ligt tussen 139 en 558 mg magnesium per dag,

wat betekent dat een deel van de bevolking onvoldoende magnesium binnenkrijgt.32 De ADH is voldoende om magnesiumdeficiëntie te voorkomen,

maar is vermoedelijk te laag voor de preventie van

(chronische) ziekten. 34 Het dieet van onze verre

voorouders bevatte naar schatting 600 mg magnesium per dag. Dit is mogelijk de hoeveelheid

magnesium die ons lichaam nodig heeft om goed

te functioneren (homeostatische mechanismen en

genoom zijn niet verschillend van onze verre voorouders).34

Mogelijke toepassingen voor magnesiumsuppletie genoemd in wetenschappelijke literatuur:

• Lage inname van magnesium uit voeding.

• Verlaging van de magnesiumstatus door onder

meer braken, excessief zweten, alcoholisme,

(acute, chronische) diarree, malabsorptie (syndromen), pancreatitis, cystische fibrose, metabole acidose en chronische nierziekten.33,50

• Diabetes type 2: diabetes type 2 wordt gekenmerkt door cellulaire en extracellulaire magnesiumdepletie; magnesiumsuppletie verlaagt

de nuchtere glucosespiegel, verhoogt de insulinegevoeligheid, verhoogt het (gunstige) HDLcholesterol en verbetert de glycemische controle; verbetering van de magnesiumstatus zou

mogelijk vasculaire diabetescomplicaties en

voetulcers tegen kunnen gaan.40,52-55

3

• (Preventie) metabool syndroom: magnesiumsuppletie verbetert de glucosestofwisseling

bij (gezonde) ouderen; verhoging van de mag­

nesium­inname is geassocieerd met verlaging

van de nuchtere insulinespiegel.41,56

• Osteoporose 34,57,58: een hogere magnesiuminname uit voeding en voedingssupplementen is

positief geassocieerd met de botmineraaldichtheid bij ouderen.58

• (Top)sport: magnesiumsuppletie kan spierfunctie, spierkracht en uithoudingsvermogen

bij (top)sporters verbeteren.59

• Bij diverse hartziekten kan magnesiumsuppletie mogelijk een rol spelen 35,60-68

• Een aantal studies beschrijven de rol van

magnesium bij zwangerschapscomplicaties:

(pre)eclampsie 35,43, preventie vroeggeboorte.47

• Premenstrueel syndroom: eventueel in combinatie met vitamine B6.69,70

• Migraine.71

• Astma bij kinderen45

op), vegetariërs en veganisten (vlees is de rijkste

bron van zink; daarbij is zink uit plantaardige bronnen moeilijker opneembaar dan uit dierlijke bronnen), vrouwen die zwanger zijn of borstvoeding

geven (verhoogde zinkbehoefte) en (chronisch)

zieken (slechte voedingsstatus, verhoogde zinkbehoefte).73 Deze groepen kunnen baat hebben bij

een zinksupplement.

Een (mild) zinktekort kan allerlei (niet-specifieke)

klachten veroorzaken waaronder afname van de

weerstand (vooral celgemedieerde immuniteit),

vertraagde wondheling, vertraagde groei en ontwikkeling bij kinderen, vermoeidheid, moeite met

denken, emotionele klachten, verminderde vruchtbaarheid, haaruitval, nachtblindheid, diarree,

afname van de botmineraaldichtheid en verstoorde

reuk- en smaakzin.73,74,77 Dermatitis treedt pas op

bij een ernstig zinktekort.73

Bepalen zinkstatus

Er is nog geen gouden standaard voor het bepalen

van de zinkstatus.73 De plasma- of serumzinkspiegel is alleen geschikt om een ernstig zinktekort

vast te stellen. Een wat gevoeliger parameter is

het zinkgehalte in witte bloedcellen.1,73

Dosering en veiligheid

Magnesium heeft een lage toxiciteit bij mensen

met een normale nierfunctie, omdat een teveel

snel wordt uitgescheiden door de nieren. Bij nierziekten moet de magnesiumspiegel goed gemonitord worden. 32,33 Diarree kan optreden bij doses

vanaf 250-500 mg/dag en de UL (upper limit) voor

magnesium (uitsluitend uit voedingssupplementen) is mede daarom vastgesteld op 250 mg/dag.32

Een inadequate zinkinname beïnvloed mogelijk de

gezondheid. Verschillende ziekten kunnen bijdragen aan verhoging van de zinkbehoefte, bijvoorbeeld door verminderde opname, verhoogde uitscheiding of toegenomen verbruik van zink.

Zink

Functies zink

Zink is bestanddeel van duizenden eiwitstructuren en is als cofactor onmisbaar voor de activiteit

van meer dan 300 enzymen die uiteenlopende biochemische reacties kalalyseren.73,74 Dit betekent

dat veel fysiologische processen in het lichaam

zinkafhankelijk zijn. Zink is onder meer belangrijk voor groei en ontwikkeling, stofwisseling,

energie­productie, immuunsysteem, antioxidatieve

bescherming, wondheling en weefselvernieuwing,

voortplanting, zintuigen en zenuwstelsel.1,73,75

Mogelijke toepassingen voor zinksuppletie

genoemd in wetenschappelijke literatuur:

• Lage inname van zink uit voeding.

• Verminderde weerstand bij (gezonde) ouderen

(boven 55 jaar): leeftijdsgerelateerde achteruitgang van het immuunsysteem (immunosenescense) is gerelateerd aan leeftijdsgerelateerde

afname van de zinkstatus en wordt tegengegaan door zinksuppletie.1,86,87

• Vaccinatie: zinksuppletie kan de effectiviteit van

vaccinatie verhogen, met name als tijdig (minimaal een maand voorafgaande aan vaccinatie)

met zinksuppletie wordt gestart.1

• Infectieziekten: verkoudheid 88; diarree 1,89,90;

(acute) infecties van de onderste luchtwegen

1,91,92

; HIV-infectie 1,74; tuberculose 1,93; malaria

94-96

; leishmaniasis.1,97

Verlaagde zinkstatus

In Nederland is de hoeveelheid zink in voeding

vaak aan de magere kant.76 Een (subklinisch)

zinktekort komt vermoedelijk vaak voor, tenzij de

voeding geregeld wordt aangevuld met een multisupplement met zink.74 Groepen die extra risico

lopen op een zinktekort zijn ouderen (ze eten minder en vaak eenzijdiger en nemen zink minder goed

4

Selenium

• Intestinale malabsorptie door onder meer coeliakie en cystische fibrose (taaislijmziekte).73,74

• Inflammatoire darmziekten: ziekte van Crohn,

colitis ulcerosa.73,74

• Bloedverlies door menorragie, hemolytische

anemie (sikkelcelziekte, thalassemie) of een

parasitaire infectie.1,73,98

• Chronische nierziekten.73

• Acute en chronische leverziekten, alcoholisme.73,74,99

• Chronische ontstekingsziekten waaronder

reumatoïde artritis en psoriatrische artritis.1,73,100,101

• Diabetes type 1 en 2: zink heeft een insulinomimetische werking, beschermt tegen oxidatieve stress door diabetes en helpt mogelijk

diabetescomplicaties (waaronder diabetische

neuropathie) tegen te gaan.1,73,102-105 Het is nog

onduidelijk of zinksuppletie zorgt voor een

betere glycemische controle.1

• Aangeboren ziekten: acrodermatitis enterohepatica, ziekte van Wilson en syndroom van

Down.1,74,106,107

• Leeftijdsgerelateerde maculadegeneratie

(AMD).1,108

• Huidproblemen: vertraagde wondheling, zweren, acne, rosacea, brandwonden.1,109-111

• Recidiverende orale ulceraties (aften).1,112

• Maagzweren.113

• Bestraling: zinksuppletie kan mogelijk stralingsgeïnduceerde smaakafwijkingen bij kankerpatiënten verminderen.115

• Psychische stoornissen: depressie, ADHD en

anorexia nervosa (casusbeschrijvingen).1,116-119

• Tinnitus (met name bij een goed gehoor).120

• COPD (chronische obstructieve longziekte).121

Functies selenium

Het essentiële spoorelement selenium (seleen)

maakt deel uit van selenoproteïnen, die uiteenlopende functies vervullen in het lichaam. Selenium

is onder meer van belang voor groei en ontwikkeling, energieproductie, immuunsysteem, regulatie van ontstekingsprocessen, bescherming tegen

zware metalen, antioxidantbescherming, leverdetoxificatie, signaaloverdracht, metabolisme van

essentiële aminozuren, synthese van schildklierhormoon, hersenfunctie, spierfunctie en voortplanting.125-130

Verlaagde seleniumstatus

Wereldwijd verschilt de inname van selenium uit

voeding aanzienlijk, afhankelijk van het seleniumgehalte in de bodem. Vlees, vis, zuivel, eieren en

granen zijn belangrijke bronnen van selenium.128

In Nederland is de seleniuminname uit voeding

gemiddeld 39 tot 67 mcg per dag, terwijl een volwassene circa 70 mcg (of 1 mcg per kilogram

lichaamsgewicht per dag) nodig heeft voor het

handhaven van de seleniumbalans.126,130,131 Vegetariërs en veganisten hebben vaak een lagere seleniuminname dan omnivoren.128 De seleniumstatus

neemt af bij het ouder worden.131

Een ernstig seleniumtekort, dat wordt gezien in

sommige delen van China en Siberie, leidt tot Keshanziekte (juveniele cardiomyopathie) en KashinBeckziekte (osteoartropathie) en zorgt tot degeneratie van de alvleesklier.125,126,128 Verlaging van de

seleniumstatus is mogelijk geassocieerd met een

verminderde weerstand, vermoeidheid, degeneratieve veranderingen in de lever, toename van oxidatieve stress en ontstekingsactiviteit, verhoging

van de homocysteïnespiegel, cognitieve achteruitgang bij ouderen, depressie en een toegenomen

kans op hypothyroïdie, osteoporose, hart- en vaatziekten, overgewicht/obesitas en bepaalde vormen

van kanker.125,128-130,132,135-143,175

Dosering en veiligheid

De aanbevolen dagelijkse hoeveelheid (ADH) voor

zink uit voeding en voedingssupplementen is 10-15

mg voor volwassenen; voor een zwangere vrouw

20 mg en een zogende vrouw 25 mg per dag.122

De veilige bovengrens (UL ofwel Upper Limit)

bedraagt 25 mg zink per dag voor volwassenen

en respectievelijk 7, 10, 13, 18 en 22 mg zink per

dag voor kinderen van 1-3, 4-6, 7-10, 11-14 en 1517 jaar.123 Hierbij dient de koperinname voldoende

te zijn (verhouding zink:koper maximaal 10:115:1).1,73,122 Het gebruik door volwassenen van zinksupplementen met 15 mg elementair zink is in de

regel veilig.124 Hogere (therapeutische) doses zink

worden het beste alleen op voorschrift van een

deskundige gebruikt.

Bepalen seleniumstatus

Het seleniumgehalte in bloed(plasma) of serum

geeft een goede indicatie van de seleniumstatus

en seleniuminname; het seleniumgehalte in haar

en nagels weerspiegelt de seleniumstatus over

een langere periode.128

5

• (Preventie) metabool syndroom: magnesiumsuppletie verbetert de glucosestofwisseling

bij (gezonde) ouderen; verhoging van de mag­

nesium­inname is geassocieerd met verlaging

van de nuchtere insulinespiegel.41,56

• Osteoporose 34,57,58: een hogere magnesiuminname uit voeding en voedingssupplementen is

positief geassocieerd met de botmineraaldichtheid bij ouderen.58

• (Top)sport: magnesiumsuppletie kan spierfunctie, spierkracht en uithoudingsvermogen

bij (top)sporters verbeteren.59

• Bij diverse hartziekten kan magnesiumsuppletie mogelijk een rol spelen 35,60-68

• Een aantal studies beschrijven de rol van

magnesium bij zwangerschapscomplicaties:

(pre)eclampsie 35,43, preventie vroeggeboorte.47

• Premenstrueel syndroom: eventueel in combinatie met vitamine B6.69,70

• Migraine.71

• Astma bij kinderen45

op), vegetariërs en veganisten (vlees is de rijkste

bron van zink; daarbij is zink uit plantaardige bronnen moeilijker opneembaar dan uit dierlijke bronnen), vrouwen die zwanger zijn of borstvoeding

geven (verhoogde zinkbehoefte) en (chronisch)

zieken (slechte voedingsstatus, verhoogde zinkbehoefte).73 Deze groepen kunnen baat hebben bij

een zinksupplement.

Een (mild) zinktekort kan allerlei (niet-specifieke)

klachten veroorzaken waaronder afname van de

weerstand (vooral celgemedieerde immuniteit),

vertraagde wondheling, vertraagde groei en ontwikkeling bij kinderen, vermoeidheid, moeite met

denken, emotionele klachten, verminderde vruchtbaarheid, haaruitval, nachtblindheid, diarree,

afname van de botmineraaldichtheid en verstoorde

reuk- en smaakzin.73,74,77 Dermatitis treedt pas op

bij een ernstig zinktekort.73

Bepalen zinkstatus

Er is nog geen gouden standaard voor het bepalen

van de zinkstatus.73 De plasma- of serumzinkspiegel is alleen geschikt om een ernstig zinktekort

vast te stellen. Een wat gevoeliger parameter is

het zinkgehalte in witte bloedcellen.1,73

Dosering en veiligheid

Magnesium heeft een lage toxiciteit bij mensen

met een normale nierfunctie, omdat een teveel

snel wordt uitgescheiden door de nieren. Bij nierziekten moet de magnesiumspiegel goed gemonitord worden. 32,33 Diarree kan optreden bij doses

vanaf 250-500 mg/dag en de UL (upper limit) voor

magnesium (uitsluitend uit voedingssupplementen) is mede daarom vastgesteld op 250 mg/dag.32

Een inadequate zinkinname beïnvloed mogelijk de

gezondheid. Verschillende ziekten kunnen bijdragen aan verhoging van de zinkbehoefte, bijvoorbeeld door verminderde opname, verhoogde uitscheiding of toegenomen verbruik van zink.

Zink

Functies zink

Zink is bestanddeel van duizenden eiwitstructuren en is als cofactor onmisbaar voor de activiteit

van meer dan 300 enzymen die uiteenlopende biochemische reacties kalalyseren.73,74 Dit betekent

dat veel fysiologische processen in het lichaam

zinkafhankelijk zijn. Zink is onder meer belangrijk voor groei en ontwikkeling, stofwisseling,

energie­productie, immuunsysteem, antioxidatieve

bescherming, wondheling en weefselvernieuwing,

voortplanting, zintuigen en zenuwstelsel.1,73,75

Mogelijke toepassingen voor zinksuppletie

genoemd in wetenschappelijke literatuur:

• Lage inname van zink uit voeding.

• Verminderde weerstand bij (gezonde) ouderen

(boven 55 jaar): leeftijdsgerelateerde achteruitgang van het immuunsysteem (immunosenescense) is gerelateerd aan leeftijdsgerelateerde

afname van de zinkstatus en wordt tegengegaan door zinksuppletie.1,86,87

• Vaccinatie: zinksuppletie kan de effectiviteit van

vaccinatie verhogen, met name als tijdig (minimaal een maand voorafgaande aan vaccinatie)

met zinksuppletie wordt gestart.1

• Infectieziekten: verkoudheid 88; diarree 1,89,90;

(acute) infecties van de onderste luchtwegen

1,91,92

; HIV-infectie 1,74; tuberculose 1,93; malaria

94-96

; leishmaniasis.1,97

Verlaagde zinkstatus

In Nederland is de hoeveelheid zink in voeding

vaak aan de magere kant.76 Een (subklinisch)

zinktekort komt vermoedelijk vaak voor, tenzij de

voeding geregeld wordt aangevuld met een multisupplement met zink.74 Groepen die extra risico

lopen op een zinktekort zijn ouderen (ze eten minder en vaak eenzijdiger en nemen zink minder goed

4

Selenium

• Intestinale malabsorptie door onder meer coeliakie en cystische fibrose (taaislijmziekte).73,74

• Inflammatoire darmziekten: ziekte van Crohn,

colitis ulcerosa.73,74

• Bloedverlies door menorragie, hemolytische

anemie (sikkelcelziekte, thalassemie) of een

parasitaire infectie.1,73,98

• Chronische nierziekten.73

• Acute en chronische leverziekten, alcoholisme.73,74,99

• Chronische ontstekingsziekten waaronder

reumatoïde artritis en psoriatrische artritis.1,73,100,101

• Diabetes type 1 en 2: zink heeft een insulinomimetische werking, beschermt tegen oxidatieve stress door diabetes en helpt mogelijk

diabetescomplicaties (waaronder diabetische

neuropathie) tegen te gaan.1,73,102-105 Het is nog

onduidelijk of zinksuppletie zorgt voor een

betere glycemische controle.1

• Aangeboren ziekten: acrodermatitis enterohepatica, ziekte van Wilson en syndroom van

Down.1,74,106,107

• Leeftijdsgerelateerde maculadegeneratie

(AMD).1,108

• Huidproblemen: vertraagde wondheling, zweren, acne, rosacea, brandwonden.1,109-111

• Recidiverende orale ulceraties (aften).1,112

• Maagzweren.113

• Bestraling: zinksuppletie kan mogelijk stralingsgeïnduceerde smaakafwijkingen bij kankerpatiënten verminderen.115

• Psychische stoornissen: depressie, ADHD en

anorexia nervosa (casusbeschrijvingen).1,116-119

• Tinnitus (met name bij een goed gehoor).120

• COPD (chronische obstructieve longziekte).121

Functies selenium

Het essentiële spoorelement selenium (seleen)

maakt deel uit van selenoproteïnen, die uiteenlopende functies vervullen in het lichaam. Selenium

is onder meer van belang voor groei en ontwikkeling, energieproductie, immuunsysteem, regulatie van ontstekingsprocessen, bescherming tegen

zware metalen, antioxidantbescherming, leverdetoxificatie, signaaloverdracht, metabolisme van

essentiële aminozuren, synthese van schildklierhormoon, hersenfunctie, spierfunctie en voortplanting.125-130

Verlaagde seleniumstatus

Wereldwijd verschilt de inname van selenium uit

voeding aanzienlijk, afhankelijk van het seleniumgehalte in de bodem. Vlees, vis, zuivel, eieren en

granen zijn belangrijke bronnen van selenium.128

In Nederland is de seleniuminname uit voeding

gemiddeld 39 tot 67 mcg per dag, terwijl een volwassene circa 70 mcg (of 1 mcg per kilogram

lichaamsgewicht per dag) nodig heeft voor het

handhaven van de seleniumbalans.126,130,131 Vegetariërs en veganisten hebben vaak een lagere seleniuminname dan omnivoren.128 De seleniumstatus

neemt af bij het ouder worden.131

Een ernstig seleniumtekort, dat wordt gezien in

sommige delen van China en Siberie, leidt tot Keshanziekte (juveniele cardiomyopathie) en KashinBeckziekte (osteoartropathie) en zorgt tot degeneratie van de alvleesklier.125,126,128 Verlaging van de

seleniumstatus is mogelijk geassocieerd met een

verminderde weerstand, vermoeidheid, degeneratieve veranderingen in de lever, toename van oxidatieve stress en ontstekingsactiviteit, verhoging

van de homocysteïnespiegel, cognitieve achteruitgang bij ouderen, depressie en een toegenomen

kans op hypothyroïdie, osteoporose, hart- en vaatziekten, overgewicht/obesitas en bepaalde vormen

van kanker.125,128-130,132,135-143,175

Dosering en veiligheid

De aanbevolen dagelijkse hoeveelheid (ADH) voor

zink uit voeding en voedingssupplementen is 10-15

mg voor volwassenen; voor een zwangere vrouw

20 mg en een zogende vrouw 25 mg per dag.122

De veilige bovengrens (UL ofwel Upper Limit)

bedraagt 25 mg zink per dag voor volwassenen

en respectievelijk 7, 10, 13, 18 en 22 mg zink per

dag voor kinderen van 1-3, 4-6, 7-10, 11-14 en 1517 jaar.123 Hierbij dient de koperinname voldoende

te zijn (verhouding zink:koper maximaal 10:115:1).1,73,122 Het gebruik door volwassenen van zinksupplementen met 15 mg elementair zink is in de

regel veilig.124 Hogere (therapeutische) doses zink

worden het beste alleen op voorschrift van een

deskundige gebruikt.

Bepalen seleniumstatus

Het seleniumgehalte in bloed(plasma) of serum

geeft een goede indicatie van de seleniumstatus

en seleniuminname; het seleniumgehalte in haar

en nagels weerspiegelt de seleniumstatus over

een langere periode.128

5

Mogelijke toepassingen voor seleniumsuppletie

genoemd in wetenschappelijke onderzoeken:

Er zijn aanwijzingen dat een goede seleniumstatus bijdraagt aan de preventie en remming van

leeftijdsgerelateerde degeneratieve aandoeningen.128,135,144-147

Seleniumsuppletie kan een rol spelen bij:

• Lage inname van selenium uit voeding.128

• Verhoogde seleniumbehoefte bij ziekten die

gepaard gaan met toename van oxidatieve

stress (onder meer astma, reumatoïde artritis,

hart- en vaatziekten, ontstekingsziekten, infectieziekten).127,128,149-151

• Zware metalenbelasting (kwik, lood, cadmium),

leverziekten, roken.127,128,152

• Verminderde weerstand bij ouderen.127,153

• Diabetes: preventie micro- en macrovasculaire

diabetescomplicaties158 waaronder diabetische

nefropathie159, ondersteuning functie eilandjes

van Langerhans.160

• Verminderd vruchtbare mannen met een lage

selenium status. Selenium zou de spermamotiliteit kunnen verbeteren en daarmee de kans

op een succesvolle conceptie .161

• Zwangerschap: een lage seleniumstatus is

geassocieerd met pre-eclampsie162 , miskraam163,164 en vroeggeboorte176; Selenium zou

een actieve rol kunnen spelen bij de bescherming van moeder en kind tegen milieutoxines152

• Virale infecties127: verhoging van de seleniumstatus kan de kans op leverkanker bij patiënten

met hepatitis B/C verlagen127,138,165; verhoging

van de seleniumstatus verbetert de prognose

bij een HIV-infectie.127,166,167

• Kritieke ziekte (trauma, sepsis, brandwonden,

ARDS).172

• Depressie (vooral bij een suboptimale seleniumstatus).142,173

Referenties

1.

2.

3.

4.

5. 6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21. 22. 23. 24. 25. 26. 27. Dosering en veiligheid

De Scientific Committee for Food heeft een aanvaardbare bovengrens voor inname (UL=upper

limit) van 300 microgram per dag voor volwassenen vastgesteld. Deze bovengrens geldt ook voor

zwangere en zogende vrouwen.126 In de Verenigde

Staten geldt een UL van 400 mcg per dag.128 Seleniummethionine, een organisch gebonden vorm van

selenium die in voeding voorkomt, heeft een hoge

biologische beschikbaarheid en wordt veel beter

opgenomen dan anorganische vormen zoals natriumseleniet.128,174,175 Langdurige inname van selenium (uit voeding en voedingsupplementen) boven

de UL-waarde moet worden vermeden.

28. 29. 30. 31. 32. 33. 34. 35. 36. 6

Haase H, Overbeck S, Rink L. Zinc supplementation for the treatment or

prevention of disease: current status and future perspectives. Exp Gerontol. 2008;43(5):394-408.

van Mierlo LA, Arends LR, Streppel MT et al. Blood pressure response to

calcium supplementation: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Hum Hypertens. 2006;20(8):571-80.

Heaney RP. Calcium intake and disease prevention. Arq Bras Endocrinol

Metabol. 2006;50(4):685-93.

Adams J, Pepping J. Vitamin K in the treatment and prevention of

osteoporosis and arterial calcification. Am J Health Syst Pharm.

2005;62(15):1574-81.

Gezondheidsraad. Voedingsnormen: calcium, vitamine D, thiamine, riboflavine, niacine, pantotheenzuur en biotine. Den Haag: Gezondheidsraad,

2000;publicatie nr 2000/12.

Zo eet Nederland: resultaten van de Voedselconsumptiepeiling 19971998. Den Haag: Voedingscentrum, 1998.

Thys-Jacobs S. Micronutrients and the premenstrual syndrome: the case

for calcium. J Am Coll Nutr. 2000;19(2):220-7.

Jorde R, Sundsfjord J, Haug E et al. Relation between low calcium

intake, parathyroid hormone, and blood pressure. Hypertension.

2000;35(5):1154-9.

Dwyer JH, Dwyer KM, Scribner RA et al. Dietary calcium, calcium supplementation, and blood pressure in African American adolescents. Am J

Clin Nutr. 1998 Sep;68(3):648-55.

Houston MC, Harper KJ. Potassium, magnesium, and calcium: their role

in both the cause and treatment of hypertension. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2008;10(7 Suppl 2):3-11.

Bertone-Johnson ER, Hankinson SE, Bendich A et al. Calcium and vitamin

D intake and risk of incident premenstrual syndrome. Arch Intern Med.

2005;165(11):1246-52.

Jacqmain M, Doucet E, Després JP et al. Calcium intake, body composition, and lipoprotein-lipid concentrations in adults. Am J Clin Nutr.

2003;77(6):1448-52.

DeJongh ED, Binkley TL, Specker BL. Fat mass gain is lower in calciumsupplemented than in unsupplemented preschool children with low dietary calcium intakes. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84(5):1123-7.

Lappe JM, Travers-Gustafson D, Davies KM et al. Vitamin D and calcium

supplementation reduces cancer risk: results of a randomized trial. Am J

Clin Nutr. 2007;85(6):1586-91.

Black RE, Williams SM, Jones IE et al. Children who avoid drinking cow

milk have low dietary calcium intakes and poor bone health. Am J Clin

Nutr. 2002;76(3):675-80.

Theobald HE. Dietary calcium and health. British Nutrition Foundation

Nutrition Bulletin 2005;30:237-277.

Gough H, Goggin T, Bissessar A et al. A comparative study of the relative

influence of different anticonvulsant drugs, UV exposure and diet on vitamin D and calcium metabolism in out-patients with epilepsy. Q J Med.

1986;59(230):569-77.

Reid IR, Ibbertson HK. Calcium supplements in the prevention of steroidinduced osteoporosis. Am J Clin Nutr. 1986;44(2):287-90.

Friedman PA, Bushinsky DA. Diuretic effects on calcium metabolism. Semin Nephrol. 1999;19(6):551-6.

Abrams SA, O’Brien KO. Calcium and bone mineral metabolism in children with chronic illnesses. Annu Rev Nutr. 2004;24:13-32.

Heaney RP. Calcium needs of the elderly to reduce fracture risk. J Am

Coll Nutr. 2001;20(2S): 192S-197S.

Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Rees JR, Grau MV et al. Effect of calcium supplementation on fracture risk: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. Am J

Clin Nutr. 2008;87(6):1945-51.

Heaney RP, Abrams S, Dawson-Hughes B et al. Peak bone mass. Osteoporos Int. 2000;11:985–1009.

Bailey DA, Martin AD, McKay AA et al. Calcium accretion in girls

and boys during puberty: A longitudinal analysis. J Bone Miner Res.

2000;15:2245–2250.

Hofmeyr G, Duley L, Atallah A. Dietary calcium supplementation for prevention of pre-eclampsia and related problems: a systematic review and

commentary. BJOG 2007;114:933–943.

Pittas AG, Lau J, Hu FB et al. The role of vitamin D and calcium in type 2

diabetes. A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab.

2007;92(6):2017-29.

Thys-Jacobs S. Polycystic ovary syndrome and reproduction. In: Weaver

CM, Heaney RP, eds. Calcium in Human Health. New Jersey: Humana

Press, 2006. pp. 341-55.

Pereira MA, Jacobs DR, Van Horn L et al. Dairy consumption, obesity,

and the insulin resistance syndrome in young adults. J Am Med Assoc

2002;287:2081-9.

Zemel MB, Thompson W, Milstead A et al. Calcium and dairy acceleration

of weight and fat loss during energy restriction in obese adults. Obes Res

2004;12:582-90.

Zemel MB, Richard J, Mathis S et al. Dairy augmentation of total and central fat loss in obese subjects. Int J Obesity 2005;29:391-7.

Bowen J, Noakes M, Clifton PM. A high dairy protein, high-calcium diet

minimizes bone turnover in overweight adults during weight loss. J Nutr.

2004;134(3):568-73.

Kennisbank Voedselveiligheid VWA. Kennisblad magnesium (15 juli 2008).

http://www.vwa.nl/portal/page?_pageid=119,1639827&_dad=portal&_

schema=PORTAL&p_file_id=29412

Rude RK. Magnesium deficiency: a cause of heterogeneous disease in humans. J Bone Miner Res. 1998;13(4):749-58.

Vormann J. Magnesium: nutrition and metabolism. Mol Aspects Med.

2003;24(1-3):27-37.

Fawcett WJ, Haxby EJ, Male DA. Magnesium: physiology and pharmacology. Br J Anaesth. 1999;83(2):302-20.

Evangelopoulos AA, Vallianou NG, Panagiotakos DB et al. An inverse relationship between cumulating components of the metabolic syndrome and

serum magnesium levels. Nutrition Research 2008;28:659–663.

• Afvallen: calciumsuppletie tijdens afvallen

helpt botafbraak tegen te gaan kan de effectiviteit van het dieet verhogen.3,29-31

• Het verbeteren van de calcium status vermindert de kans op verschillende kankersoorten

bij postmenopauzale vrouwen.14

Magnesiumdepletie kan leiden tot een veelheid

van klachten als gebrek aan eetlust, misselijkheid, (chronische) vermoeidheid, verminderde

concentratie, nervositeit, geïrriteerdheid, toegenomen stressgevoeligheid, hartritmestoornissen,

duizeligheid, (spannings)hoofdpijn, spierkramp,

gespannen spieren, spierzwakte, tremoren, bronchiale hyperreactiviteit en afname van de longfunctie. Magnesiumdepletie is daarnaast mogelijk geassocieerd met een toegenomen kans op

overgewicht/obesitas, hypertensie, dyslipidemie,

insulineresistentie, metabool syndroom, diabetes

type 2, ischemische hartziekte, hartfalen, hartritmestoornissen, acute hartdood, osteoporose,

niet-alcoholische leververvetting, mentale problemen (depressie, psychose), migraine, astma,

zwangerschapsproblemen (pre-eclampsie, vroeggeboorte), symptomatische galstenen en convulsies. 33-48 Magnesiumdepletie leidt tot verstoring

van de vitamine D-stofwisseling en/of vitamine Dactiviteit, kaliumdepletie en calciumdepletie (door

afname van de secretie van parathormoon); een

kalium- of calciumsupplement heeft onvoldoende

effect als de magnesiumstatus verlaagd is.33

Dosering en veiligheid

De Gezondheidsraad heeft de aanvaardbare bovengrens van inname van calcium (uit voeding en voedingssupplementen) vastgesteld op 2500 mg/dag

(vanaf 1-jarige leeftijd).5 Dit betekent dat suppletie

met (maximaal) 1000-1500 mg calcium per dag,

naast (niet met calcium verrijkte) voeding voor de

meeste mensen geen problemen oplevert.

Magnesium

Functies magnesium

In het lichaam fungeert magnesium vooral als

(essentiële) co-factor van honderden enzymen, die

onder meer betrokken zijn bij de energieproductie,

celsignalering, glucose-, insuline- en lipidenstofwisseling, DNA-transcriptie, celdeling en eiwit- en

nucleïnezuursynthese. 32,33 Magnesium heeft een

stabiliserend en beschermend effect op membranen en is belangrijk voor de zenuwgeleiding, vaaten spiertonus, antioxidantbescherming, afweer,

hormoonhuishouding, opbouw van botten en tanden, natrium-, kalium-, calciumbalans en vitamine

D-stofwisseling.

Bepalen magnesiumstatus

Slechts 1% van het magnesium bevindt zich in

de extracellulaire ruimte, de rest bevindt zich in

lichaamscellen en botweefsel. Met het bepalen van

het magnesiumgehalte in serum kan alleen een

ernstig magnesiumtekort worden vastgesteld. 33

Een beter beeld van de magnesiumstatus geeft de

magnesiumbelastingstest.49

Verlaagde magnesiumstatus

De gehaltes van magnesium in levensmiddelen

lopen aanzienlijk uiteen. Magnesiumbronnen zijn

onder meer cacao, garnalen, groene groenten,

noten, peulvruchten, zuivel en (volkoren)granen.

De ADH voor magnesium is 250-300 mg/dag voor

vrouwen en 300-350 mg/dag voor mannen. De

geschatte inname van magnesium in Nederland

ligt tussen 139 en 558 mg magnesium per dag,

wat betekent dat een deel van de bevolking onvoldoende magnesium binnenkrijgt.32 De ADH is voldoende om magnesiumdeficiëntie te voorkomen,

maar is vermoedelijk te laag voor de preventie van

(chronische) ziekten. 34 Het dieet van onze verre

voorouders bevatte naar schatting 600 mg magnesium per dag. Dit is mogelijk de hoeveelheid

magnesium die ons lichaam nodig heeft om goed

te functioneren (homeostatische mechanismen en

genoom zijn niet verschillend van onze verre voorouders).34

Mogelijke toepassingen voor magnesiumsuppletie genoemd in wetenschappelijke literatuur:

• Lage inname van magnesium uit voeding.

• Verlaging van de magnesiumstatus door onder

meer braken, excessief zweten, alcoholisme,

(acute, chronische) diarree, malabsorptie (syndromen), pancreatitis, cystische fibrose, metabole acidose en chronische nierziekten.33,50

• Diabetes type 2: diabetes type 2 wordt gekenmerkt door cellulaire en extracellulaire magnesiumdepletie; magnesiumsuppletie verlaagt

de nuchtere glucosespiegel, verhoogt de insulinegevoeligheid, verhoogt het (gunstige) HDLcholesterol en verbetert de glycemische controle; verbetering van de magnesiumstatus zou

mogelijk vasculaire diabetescomplicaties en

voetulcers tegen kunnen gaan.40,52-55

3

Mogelijke toepassingen voor calciumsuppletie

genoemd in wetenschappelijke literatuur:

• Lage inname van calcium uit voeding (mijden

van zuivel).

• Gebruik van medicijnen die de calciumbehoefte

verhogen waaronder anticonvulsiva (phenytoïne, fenobarbital, carbamazepine), corticosteroïden en lisdiuretica.17-19

• Darmaandoeningen: inflammatoire darmziekten en coeliakie gaan gepaard met verminderde

opname van calcium en/of vitamine D en/of verlies van calcium via calciumbevattende darm­

epitheelcellen.20

• Preventie (en behandeling) osteoporose en botbreuken: een calciuminname (uit voeding en

supplementen) van 1300–1700 mg/dag stopt

leeftijdsgerelateerde botafname en verlaagt de

kans op botbreuken bij ouderen boven 65 jaar

beter dan de aanbevolen calciuminname van

1200 mg/dag.21 Suppletie met 1200 mg calcium

per dag gedurende 4 jaar zorgde voor significante verlaging van de kans op botbreuken bij

oudere proefpersonen. 22 Het aanbieden van

voldoende calcium tijdens de groeispurt van

kinderen helpt bij het bereiken van een hoge

piekbotmassa en is een goede strategie om de

kans op leeftijdsgerelateerde osteoporose te

verkleinen.23,24

• Hypertensie (preventie): calciumsuppletie heeft

mogelijk een licht bloeddrukverlagend effect bij

hypertensie, met name bij een lage calciuminname uit voeding (‹ 800 mg/dag).2,9 Nog belangrijker is dat verbetering van de calciuminname

(maar ook de kalium en magnesium inname) via

een verhoogde consumptie van fruit en groenten de bloeddruk verbetert.10

• Calciumsuppletie lijkt het risico van preeclampsie te verminderen.25

• Diabetes type 2: een optimale inname van calcium (en vitamine D) kan de glycemische controle verbeteren.26

• Premenstrueel syndroom (PMS): suppletie met

1000-1200 mg calcium per dag kan de ernst van

PMS-klachten (stemmings- en gedragsveranderingen, pijn, vochtretentie) met 50% verlagen.7,11

• Calcium speelt mogelijk een rol bij Polycysteuze ovaria.3,27

• Overgewicht: mensen met overgewicht hebben

40% meer kans obees te worden wanneer hun

calciuminname laag is.28

calciuminname uit voeding wordt calcium aan de

botten onttrokken en neemt de renale uitscheiding

van calcium af om de calciumbloedspiegel constant te houden. Vitamine D bevordert de calcium­

absorptie en –depositie; vitamine K2 bevordert de

afzetting van calcium in botweefsel en gaat verkalking van zachte weefsels (bloedvaten, nieren etc.)

tegen.4

Verlaagde calciumstatus

Veel Nederlanders hebben een suboptimale calciuminname. 5,6 Volgens de Gezondheidsraad

bedraagt de adequate inneming van calcium voor

1-3 jaar: 500 mg/dag; 4-8 jaar: 700 mg/d; 9-18 jaar:

1100 mg/dag (jongens) en 1200 mg/d (meisjes);

19-50 jaar: 1000 mg/dag; 51-70 jaar: 1100 mg/dag

en › 70 jaar: 1200 mg/dag.5 De feitelijke (gemiddelde) calciuminname is voor veel groepen (meisjes/vrouwen boven 9 jaar, mannen tussen 9-18 jaar

en boven 70 jaar) 100-300 mg/dag onder de norm.6

Dit zijn gemiddelde innamen: mensen die geen

zuivel consumeren hebben over het algemeen

grote moeite dagelijks de aanbevolen hoeveelheid calcium binnen te krijgen. Melk(producten) en

kaas vormen de belangrijkste bron van calcium in

Nederlandse voeding en leveren circa 70% van het

benodigde calcium. Andere bronnen van calcium

zijn groenten, bonen, noten en zaden. De huidige

aanbevelingen zijn mogelijk te laag voor een optimale calciumstatus en calciumgerelateerde ziektepreventie, met name bij ouderen.3

Hypocalcemie kan zich onder meer uiten in klachten

als vermoeidheid, angst, neerslachtigheid, geheugenproblemen, prikkelbaarheid en spierkrampen.7

Een lage calciuminname leidt tot afname van de

botmineraaldichtheid, waardoor sneller botbreuken optreden, en is mogelijk geassocieerd met een